An Example of Service-Learning Success

Published Oct 07, 2021 by

Introduction

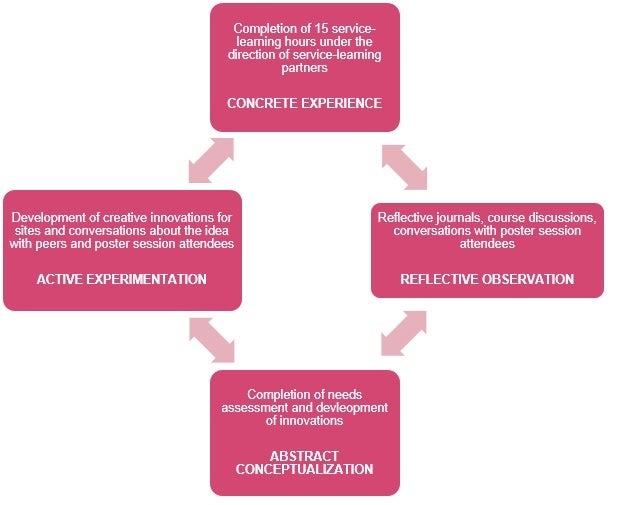

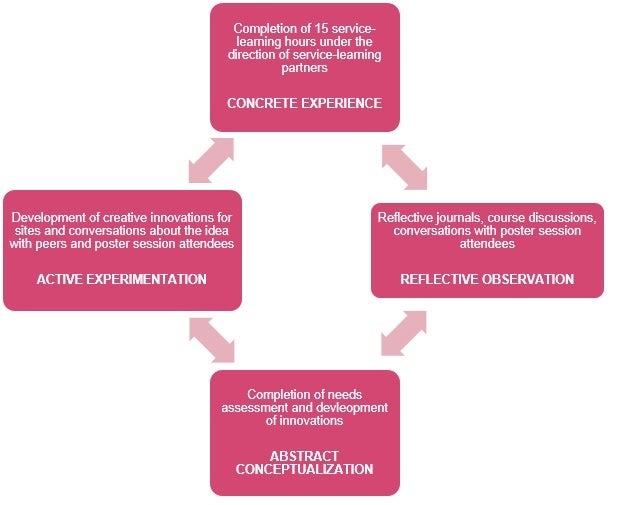

Service-learning is a pedagogical practice with unique benefits: increasing community connectedness, broadening student perspectives, providing novel skill sets to students, creating a culture of service, assisting local organizations, and broadening the impact of the university on the surrounding community (1, 2). Service-learning is a form of experiential learning where students engage in structured service activities for course credit. The core of service-learning is the process of thoughtful reflection upon experiences fulfilling a community need (1). Unlike traditional volunteer work, service-learning focuses on experience, thoughtful reflection, and alignment with course content. This process of experience, reflection, and development are rooted in the four elements of Kolb’s experiential learning model: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization and active experimentation (3).

When developing a successful service-learning program, a few crucial components include establishing the community-campus partnership, making clear expectations of student outcomes, selecting relevant content for the course, planning course activities including reflection, implementing a course evaluation, building course infrastructure, sustaining the course, practicing cultural humility, and encouraging community-engaged scholarship (4).

This case study describes the process of developing a service-learning component within the structure of a nutrition course, Community Nutrition. The case study will walk through the program development, evaluation, lessons learned from the first iteration of the course, and provide useful and modifiable tools for implementing service-learning programs in similar courses. While this case study details a nutrition course, service-learning can be adapted to many disciplines.

Objectives

This case study will:

- Provide an overview of service-learning practice within the context of a Community Nutrition course

- Apply the principles of Universal Design for Learning to building a service-learning component into a course

- Demonstrate methods for evaluating a service-learning component

- Discuss challenges and methods to overcome these challenges with a service-learning component

- Equip fellow educators with tools to increase service-learning success

UDL Alignment

Service-learning (SL) aligns with many of the key components for UDL. There are interesting challenges posed by service-learning, yet it also provides alternative methods for learning which encompass the UDL principles.

Multiple Means of Action and Expression

Multiple means of action and expression are required in SL work. The work is experiential, offering means of physical action . Experiential learning, by nature, calls for multiple means of expressing and digesting information visually, auditorily, and kinesthetically . In this particular course, students report on their perceptions through in-class discussion, writing reflections in response to structured prompts, sharing photos through social media, and presentations. Throughout the semester, students are encouraged to communicate using a course Google+ community to share photos, experiences, and challenges. Students work with SL partners to develop incremental work and hour attainment goals, and instructor feedback is provided on multiple reflective journals. Students also complete a semester-long community needs assessment project in groups related to their sites to further process and apply information gained from the experience.

Multiple Means of Engagement

Engagement is a key component of SL. Students select SL partners based on their interests and are responsible for contacting the SL partners. SL partner-instructor relationships, established with the instructor, minimize potential threats and emphasize community connection based on authentic relationships. Students work one-on-one with their SL partners to plan activities that meet SL partner needs and play to the student’s strengths. SL partners are encouraged to plan activities that require students to apply previous nutrition knowledge to the task(s) at their sites.SL partners also evaluate student performance using a rubric made available to students. By nature, SL fulfills many of the engagement checkpoints as the overarching goal of SL is to develop a sense of community that extends outside the campus limits.

Instructional Practice

This case study is centered on a junior- and senior-level Community Nutrition course taught at the University of Mississippi. Community Nutrition was a well-established course at the University that had previously been taught by adjunct professors. As a required course for nutrition students, the course enrollment was and remains very high for a Community Nutrition course. Ideally, this course should have no more than 20 students per section. It is also best to have the course meet multiple times per week rather than for a long period once per week. This gives the instructor more opportunities for frequent and thoughtful discussion. I have found that classes twice a week for a little over one hour are ideal. Keep in mind the times that your partners will most often need students and try to schedule class to accommodate those times.

Critical Elements

Course Assignments

During the first course period, students are given an overview of the benefits and process of service-learning. Each service-learning partner is invited to attend the course during the first week to introduce their site to the students. In the case that the service-learning partner is unable to attend, I present in their stead. I typically will request that they provide a brief site description to ensure I accurately present the site mission and expectations.

After the first week, students are required to complete an online survey which serves two purposes: (1) to serve as a baseline survey on student perceptions and (2) to allow students to rank-order the service-learning partners with which they would like to work. In this survey, students are also encouraged to share relevant information that may alter their ability to serve with their assigned partners (language barriers, lack of transportation, living circumstances, etc.). I encourage students to maintain open lines of communication with me so that I may accommodate any needs they have during the experience.

The course has a requirement of 15 service-learning hours. I have found 15 to be a manageable requirement while still allowing for meaningful service. The number of hours required is adjustable based on the type of University and typical student extracurricular expectations.

During the course, students are required to submit three reflective journals. These journals are responses to prompts in a short (1 page, single-spaced) format and are submitted at the beginning, middle, and end of the semester. Students also participate in course discussions. During the course, students work in groups generally composed of other members serving in the same or similar service-learning sites to complete a needs assessment assignment (5,6). This needs assessment assignment mirrors a community needs assessment which is a process used to determine a nutrition problem in a specific population, seek available resources to improve the problem, and create strategies that could help mitigate the nutrition issue. Students receive class time to work on needs assessment steps, graded at multiple points during the semester. The needs assessment assignment includes the following seven steps:

- identifying the population they intend to assess which is generally the population their SL partner serves

- setting needs assessment parameters

- collecting secondary community data through the use of relevant scientific publications or government reports

- collecting anecdotal data through communication with service-learning partners

- interpreting the data

- developing creative site innovations to help serve needs identified

- sharing their findings and creative innovations during a public poster session

These steps are based on the Needs Assessment detailed in the Community Nutrition textbook written by Boyle (5). The poster session is based on practices established by Drs. Misyak and Serrano (6).

Figure 1: Demonstration of Kolb’s experiential model within the context of a Community Nutrition course

The service-learning component introduced into the Community Nutrition course was modeled after the practices of Drs. Serrano and Misyak, instructors of Community Nutrition at Virginia Tech where I received my training (6). This model included service-learning activities, reflections through class discussions and written elements, completion of a community needs assessment, development of a new innovation for the service-learning site, and a final presentation of findings and celebration with the service-learning partners. Service-learning partners are also required to complete an evaluation of each student which is factored into the student’s grade using the SL partner evaluation sheet. On this sheet, partners are also invited to write any additional course feedback that they feel is necessary to improve the course.

Elements of the course and point values are shown below in Table 1. Within the course, students also must participate in a course Google+ Community page, where students are invited to share their experience with pictures, statements, and event fliers associated with their sites. They may also use the Google+ Community to ask questions about the course. I receive alerts for new posts to the Google+ Community and referee them for appropriateness, and answer any questions that students cannot assist one another in answering. I also use the Google+ Community to post relevant news stories, and new scientific articles.

Reflective journals are designed to help students process what they are learning at their service-learning site. Other course assignments often contribute to the synthetization of what students are being exposed to at their respective sites. One class assignment is a jigsaw activity, where each student presents one government program designed to alleviate food insecurity or nutrition deficits. In many cases, students are presenting on programs that their site assists with (ex: farmers market using SNAP benefits), which helps them to further make classroom-community connections. Many students are not aware of how difficult it is to eat a well-balanced diet on SNAP benefits and find that the SNAP challenge, another course component, helps them to understand difficult dietary choices that are made. Many comments made after the SNAP challenge are from students who realize how mentally exhausting eating on such a strict budget is, and how quickly a cheap diet becomes lackluster.

| Assignment | Points Available |

| Class attendance & participation | 50 |

| Google+ Participation (beyond the basic requirements) | 20 |

| Other class assignments | 735 |

| Reflective Journals (50 pts each) | 150 |

SL Partner Feedback and hour completion KRDN 2.5

- Survey completion before (25)

- SL Feedback (100)

- Hour completion (100), must log on my.olemiss

- Survey completion after (25)

| 250 |

Needs Assessment Presentation

- Steps 13 (20)

- Steps 4&5 (10) KRDN 4.6

- Steps 6&7 (20) KRDN 1.3

- Logic Model (100)

- Peer Evaluation (25)

- Presentation (150), weighted based on peer feedback

| 325 |

| TOTAL | 1530 |

Component Evaluation

Course feedback is a critical component for service-learning as it can not only give valuable feedback to improve the experience and thus the learning outcomes, but it can also help strengthen community-university partnerships. There are many methods to evaluate a service-learning component; one of the most simple is presented in depth here. All formal evaluations require the approval of the Institutional Review Board.

Based on previous work done at Virginia Tech with Dr. Misyak, students completed two surveys to demonstrate changes in student perceptions during the course. This methodology was utilized for ease of completion, yet provides some evidence of the efficacy of the program. These questions were adapted from previous work (7,8) and results have been previously presented (9). At the University of Mississippi, these questions have also been used to evaluate the changes in perceptions by students during the first iteration of Community Nutrition with a service-learning component (10).

In the most recent evaluation, student perceptions were evaluated using a 16-item survey with 4-point Likert scale responses (strongly disagree to strongly agree) given both before and after the completion of the required 15 hours. Student responses before and after the experience were compared using paired t-tests (Table 2).

| Evaluation Statement | Pre | Post |

| Research and practice in community nutrition is complex** | 3.29 | 3.57 |

| I feel connected to the surrounding community (outside of the university)*** | 2.71 | 3.17 |

| I am considering working in the field of community nutrition | 2.64 | 2.67 |

| Service learning will provide me with valuable skills to help me with my future career | 3.64 | 3.57 |

| Service learning will provide me with an opportunity to develop skills I could not develop through classroom learning alone | 3.74 | 3.71 |

| The service experience will make me feel like I am making a difference | 3.53 | 3.62 |

| The experience will enhance my awareness of others in need | 3.69 | 3.74 |

| The experience will enhance my confidence in interacting with others | 3.71 | 3.69 |

| The service experience will provide the opportunity to improve my communication skills | 3.67 | 3.67 |

| The experience will make me realize how much I have to offer to others who are in need | 3.55 | 3.71 |

| The service experience will make me want to do community service in the future*** | 3.40 | 3.64 |

| The experience will impress upon me the many opportunities available for nutrition majors/students to serve the community | 3.60 | 3.59 |

| Community service is unrelated to nutrition | 1.45 | 1.50 |

| I will benefit, personally, from my service learning experiences | 3.69 | 3.60 |

| I will benefit, professionally, from my service learning experiences | 3.71 | 3.67 |

| I feel that nutrition education is a serious concern in Mississippi* | 3.76 | 3.91 |

| *Indicates significant differences noted by student’s t-test (p < 0.05); ** (p < 0.025); *** (p < 0.001) |

Results from this survey show that students felt more connected to the community, were encouraged to complete more service in the future, and realized the importance of nutrition education.

Other options for course evaluation include analysis of reflective journals, in-class discussions, course projects, poster presentations, and community partner evaluations (6,11). More recently, instructors of service-learning programs have examined the service-learning experience from a service-learning partner perspective rather than merely examining student learning/competency outcomes (2). This assessment was achieved through interviews with instructors, students, and nonprofit representatives.

While the structured feedback is valuable both for scholarly and course improvement purposes, I also invite students to come speak with me after the course is completed to discuss any improvements they would like to see in the course. I also invite them to leave notes in my box if they do not feel comfortable speaking with me in person. I believe that having frank feedback from students is highly valuable, even if it is limited in publishable value. I have found that the more students feel they have a voice, the more involved they tend to be during the experience.

Starting a Service-Learning Course Component

I started my position as an assistant professor in the fall and taught Community Nutrition in the following spring semester. During the fall semester, I spent many hours locating potential service-learning partners through conversations with different departments on campus, visiting local venues (ex: farmers market), contacting non-profit organizations (ex: food pantries), and through fervent internet searches. As a new hire, I was also unfamiliar with the University of Mississippi and knew very little about the city/county/state. This posed both challenges and advantages.

The most imperative piece while establishing relationships is having clear goals for your students’ learning outcomes and sharing expectations with your partners. During the first iteration, I shared these through email or phone calls with partners. However, I have found that having a more formal document is far more helpful to continually reference. It is equally important to consider community partner needs and creating a cooperative process. This model is consistent with community-based participatory research principles (12).

I highly recommend having one person who is in contact with partners, as this creates a solid institute of trust where service-learning partners feel comfortable communicating any frustrations they may have. While it is tempting to ask a teaching assistant to manage contact, it can be difficult to maintain a necessary level of trust that is vital for service-learning success as teaching assistants are transitory. This trust is absolutely paramount to establish expectations and maintain open communication (13). Over time, these relationships are not only valuable for course integrity but can help accommodate different student learning styles and open doors for student employment. However, teaching assistants can be valuable to help assign service-learning partners to students, manage hours, evaluations, and generally assist with program structure and record keeping. Additionally, teaching assistants may also want to start service-learning programs in their future appointments, and it is a great opportunity to provide the necessary training and skill development.

Lessons Learned

After reexamining the course with the Universal Design for Learning in mind, more elements of UDL can be incorporated to strength the student experience through this service-learning component. For example, after the first course experience, it was evident that both students and service-learning partners needed more clarification regarding course expectations. Formal information sheets with both students and partners would have been immensely helpful to clear confusion and keep students/partners accountable. Therefore, I worked with one of my most proactive partners to help me create valuable tools for partners and students alike. This partner suggested including a timesheet that students keep to help with the final student evaluation completed by their SL partner. The tools are included here.

Based on the feedback from the first course iteration, I have determined what information is the most critical to share and created some forms and documents to assist with data collection and delivery. SL partners provide site information prior to the beginning of the course, which is distributed to students during the first week to assist them with the selection of their preferred sites. This form has SL partner contact information, a brief site description, key dates, and common times appropriate for service-learning hour completion. SL partners are provided with a list of expectations, and students are provided with a list of expectations. SL partners are sent both expectation lists as they need to know what students have been told in class. SL requires time and patience. Sometimes students do not meet the SL partner’s expectations and it is possible that, as the instructor, stepping in to contact the SL partner will be necessary. For example, in one site students were very frustrated as their SL partner struggled with communication, often leaving students confused with expectations and scheduling. Fortunately, I was able to supplement with additional hours with a similar site. It is important to be flexible, listen to student concerns, and maintain open communication between students and partners alike.

I have recently transitioned to an online form system which helps with resource difficulties (ex: no access to a printer/scanner/Microsoft applications). Generally, student/partner expectation guides/sheets are provided in a .docx format or .pdf format unless otherwise specified. It is also simple to convert these to photo formats if needed. Before the semester and during the course, I send many email reminders and often need to text or call SL partners for reminders about the course. It is important to remember that community members are not on the same schedule as academics, and we need to be respectful of these differences. While I do provide deadlines, I try to be flexible with partners.

Anecdotally, students have reported to me that they overwhelmingly felt that they had more rewarding experiences when they interacted with people, especially in the field of nutrition. Students felt like they really make a difference when they could share nutrition education with others. It did not matter what age group or demographic. It is important that students have hands-on experience in order for the service-learning experience to be as impactful as possible.

Patience is very important, and it is critical to listen to students. Not all students will have a “best fit” site. For example, I had an exchange student with broken English take this course. I made it clear to him that if he needed any additional help he was welcome to reach out which helped to comfort him and boost his confidence. Many sites would have been challenging for him with the added language barrier and lack of transportation. He was assigned a nutrition education site where hours were accomplished in groups, and his group mates helped him through the experience. I often checked in with him before class to see how the experience was going, beyond reading reflective journals. I was thrilled to see that they were helping him. I believe he not only accomplished the course goals, but learned so much about the culture too! Maintaining a positive relationship with all students can help to navigate some challenges that may arise.

Despite the challenges posed by integrating service-learning into a course curriculum, it can be an immersive experience for students, and present learning opportunities through a multitude of modalities. SL can also be an avenue to help all students become better learners by practicing goal setting with their SL partners, applying course knowledge, and feeling like they are making a meaningful difference which is a key critical element for continued service. Maintaining positive working relationships, keeping open communication, and practicing patience are all keys to a successful service-learning experience for students, instructors, and SL partners alike. Service-learning is an appropriate pedagogy to apply the principles of UDL to engage students using “multiple means” in order to maximize learning outcomes, personal and academic, for students of all learning abilities.

Learn More

Below is a link to resources for service-learning including references to scholarly articles on service-learning, course structure, course evaluation resources, and other relevant information for developing service-learning.

University of Mississippi McLean Institute: SL Toolkit

References & Resources

Bringle RG, Hatcher JA. Implementing Service Learning in Higher Education. J High Educ. 1996;67(2):221–39.

Velez A-L, Ngaruiya K. A multidisciplinary assessment of stakeholder outcomes from service learning: Key considerations for course design. Conference on Higher Education Pedagogy; 2018 Feb 14; Blacksburg, Virginia.

Kolb D. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1984.

Connors K ed, Cashman S, Seifer S, Unverzagt M. Advancing the Healthy People 2010 Objectives through community-based education: a curriculum planning guide. In San Francisco, CA: Community–Campus Partnerships for Health; 2003.

Boyle MA. Understanding and Achieving Behavior Change. In: Community Nutrition in Action: An Entrepreneurial Approach. 7th ed. Cengage Learning; 2016. p. 87–8.

Misyak S, Culhane J, McConnell K, Serrano E. Assessment for Learning: Integration of Assessment in a Nutrition Course with a Service-Learning Component. NACTA J. 2016;60(4):358.

Piper B, DeYoung M, Lamsam G. Student perceptions of a service-learning experience. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64(2):159.

Tande DL, Wang DJ. Developing an Effective Service Learning Program: Student Perceptions of Their Experience. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2013;45(4):377–9.

Mann G, Helms J, Serrano E, Misyak S. Service-learning in a community nutrition course: Technology-enhanced strategies for assessment of student learning [Internet]. North American Colleges and Teachers of Agriculture Conference; 2015 Jun 17; Athens, GA. Available from: https://www.nactateachers.org/images/stories/2015_NACTA_Abstracts_with_T_o_C_Final_KE.pdf

Mann G, Misyak S. Service-learning in a community nutrition course: Influence of site on student perceptions. Conference on Higher Education Pedagogy; 2018 Feb 14; Blacksburg, Virginia.

Bassi S. Through a School-Based Community Project. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2011;32(3):162–7.

Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Introduction to community-based participatory research: New issues and emphases. In: Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008.

Nemire RE, Margulis L, Frenzel-Shepherd E. Prescription for a Healthy Service-Learning Course: A Focus on the Partnership. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004 Sep;68(1):28.

Service-Learning Partner Information Sheet

Goal and overview of the course name service-learning component

I am hoping to give course name students outside hands-on experience of how nutrition can impact the community, but more importantly, I am hoping that these students will walk away with a greater understanding of what drives food choices, how the food system works, and an overall greater global perspective. Each student will be assigned a service-learning (SL) partner. Throughout the semester (semester duration), times/dates determined by the needs of the SL partner, each student will complete 15 hours of service and create a final project on what they did and what was learned through the experience, which will be presented at the end-of-course poster session.

Partner responsibilities:

The SL partner’s role, in turn, would be to verify that the students did complete the hours required and to complete a short student evaluation at the end of the semester as part of the student’s grade.

- Complete the SL partner information sheet by (date) (link to form and email option)

- Attend a SL partner introduction class (date, time, and location) one time to introduce your site. If you cannot attend, please give a few points of what your site does so I may introduce your site in your stead.

- Maintain communication with assigned students

- I will send a list of the students assigned to you by (date) with emails and phone contacts. The students will be responsible for contacting you by (date).

- If able, attend the poster session on (date, time– details to come)

- Complete an evaluation sheet for each student and submit it to me, by date

Important dates:

- To participate, please submit the attached information sheet by date

- SL partner introduction classes date

- Students should have first meeting with SL partner by date

- Hours must be completed by date

- Final poster session date

- SL evaluation sheet from partner requested by date

Should you have any questions, please do not hesitate to email me, call my office, or my cell. Thank you!

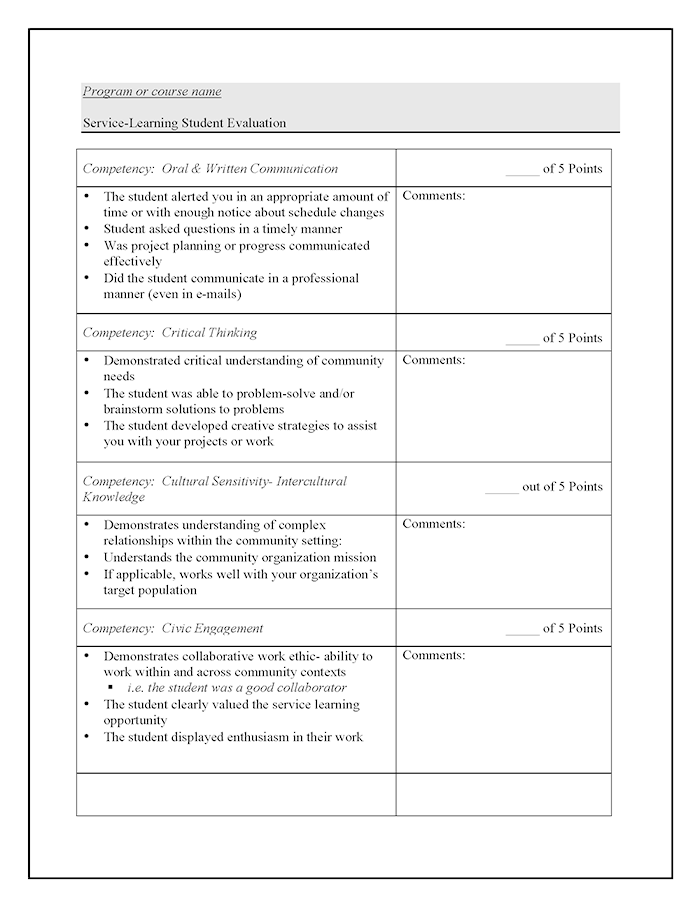

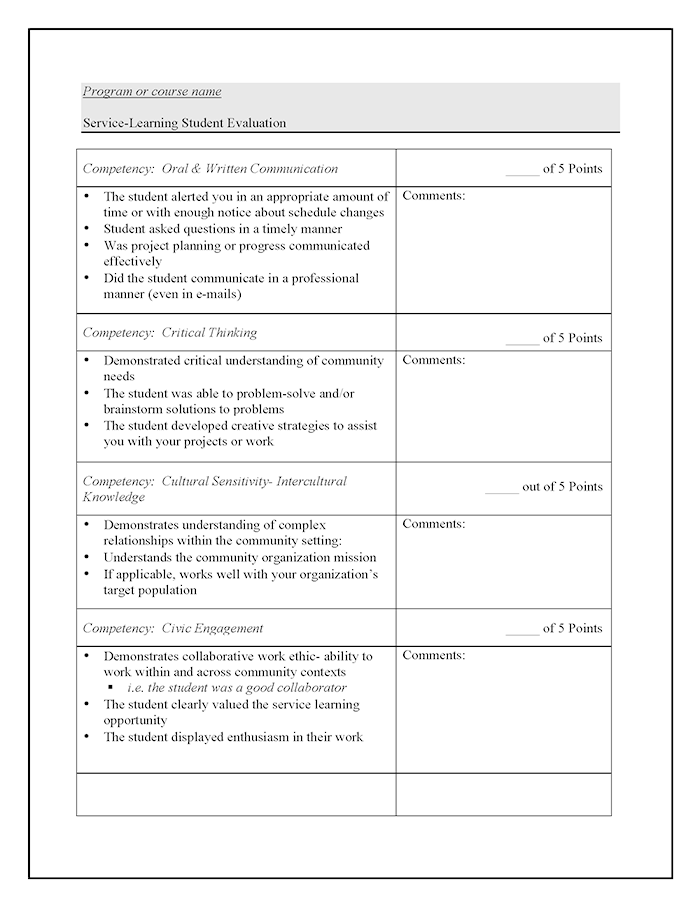

Student Evaluation

Figure 2: Student Evaluation provided by Drs. Misyak and Farris

About the Author

Georgianna Mann

Dr. Georgianna Mann is an assistant professor in the Department of Nutrition and Hospitality Management at the University of Mississippi. Originally tracked to attend veterinary school at the University of Georgia, her career path changed after becoming a teaching assistant for a study abroad program to Australia. After completing her Masters of Science in Food Science and Technology, she also received her Doctorate of Philosophy at Virginia Tech after shifting to behavioral nutrition in the Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise. Her current research is grounded in community nutrition.

Dr. Mann engages in experiential pedagogical practices of which service-learning is one. She is the current instructor for Community Nutrition as well as Experimental Foods, which is a multidisciplinary course designed to give students interprofessional experience through hands on product development and testing.