Contents

- Introduction

- Objectives

- UDL Alignment

- Instructional Practice

- Step 1: Best Groups Ever

- Step 2: Worst Groups Ever

- Step 3: Importance of Collaboration

- Step 4: Group Dynamics Homework

- Step 5: Self-Assessment

- Step 6: Self-Reflection

- Step 7: Bring Assessment Scores

- Step 8: Class Networking

- Step 9: Group Selection

- Step 10: Team Expectations Agreement

- Step 11: Group Project Evaluation Policy

- Step 12: Individual Assignments that Feed into Group Assignments

- Step 13: Personal Assessment Letter

- Step 14: Rubrics

- Step 15: Outputs and Evaluations

- Results:

- Learn More

- References & Resources

- About the Author

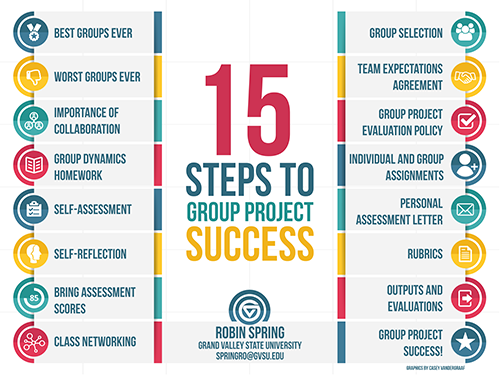

Introduction

Collaboration is an essential professional skill, yet group projects often evoke anxiety in upper-level students. The insight that inspired this 15 step process was this: Instructors often ask students to work in groups without teaching them about group communication and how the best groups function. This omission can lead to difficulty in teams and a distaste for collaborative work overall. After listening to student concerns about group projects for years and drawing on information from conferences, workshops, literature, and discussions with colleagues, I developed this process with intentional remedies to ease the main issues that cause tension in group projects. The majority of students who go through these steps report they had a good team experience and learned to appreciate the many nuances of teamwork. Students are better equipped to navigate collaborative work essential to their future.

Since implementing this formula in my classrooms, I have seen student engagement soar and quality of work substantially elevated. These 15 steps align well with the UDL model and are adaptable to a variety of circumstances where teamwork is necessary. I teach advertising/public relations courses that are well suited to the collaborative nature of the industry. Students work in teams to research, problem solve, ideate, iterate and produce strategic communication campaigns, often for real clients. These projects require critical thinking and strong team dynamics to produce valuable results. Teaching students how to work together effectively is crucial for successful outcomes, both short term and long term.

Objectives

Student Objectives

- Learn about group communication dynamics and effective teamwork.

- Reflect on how you function in a group.

- Practice effective collaboration.

- Produce creative and compelling results.

- Develop valuable portfolio pieces.

Instructor Objectives

- Address student concerns about group projects.

- Understand a 15-step process to elevate student team outcomes.

- Incorporate any or all of the 15 steps into your own group project.

- Utilize or adapt resources provided to guide group project work.

UDL Alignment

How 15 Steps to Group Project Success aligns with UDL

15 Steps to Group Project Success was designed to address various concerns from all types of learners regarding collaborative work. The steps in this process are simple for students to understand which makes the learning and assessment process transparent and supportive of a variety of student learning profiles. This method can be applied to any group project in its entirety or just the steps that make the most sense for the instructor. The 15-step process is presented in a variety of representations or media, highlights critical factors, sets up goals, provides flexibility in choices, stimulates motivation while providing ample feedback opportunities. Specifically, 15 Steps to Group Project Success aligns with UDL most closely in the following ways:

Engagement (Why):

Steps 1-14 all assist with engagement. We start by talking about their experiences in groups, positive and negative. Students are eager to share their group highlights and horror stories (steps 1,2). They want to know why collaboration is important, so we discuss the relevance to their desired career and how group work will affect them directly, or, what’s in it for them (step 3). Learning about group communication/group dynamics, and taking a short assessment of their collaborative strengths, opens their eyes as to how their work style affects them personally, making the material hit home (steps 4,5). Writing a self-reflection on what they learned about teamwork and how they may apply these concepts is a turning point. They reflect on group situations they’ve been in and now realize what went wrong. This often motivates students to be a better team player going forward (step 6).

Bringing in their assessment scores, networking with other students while discussing strengths and weaknesses and the opportunity to choose their own teams keeps them engaged in the process (steps 7,8,9). Once teams are formed, they get to decide how they will behave and be held accountable. They welcome this flexibility as they create their Team Expectations Agreement based on their group conversations (step 10). Students appreciate my policy on grading group work because they know their grade won’t be deflated if someone else doesn’t perform well, or, conversely, their grade could go down if they don’t apply themselves. This policy keeps them from tuning out and depending on others too heavily (step 11).

The individual assignments keep students accountable while learning on their own. They have the latitude to come up with their own solutions to present to the group (step 12). The personal assessment letter gives them a format to tell the instructor directly what really happened in their group; how it performed, what their challenges were and what they learned without pressure from their teammates. They are grateful for the opportunity to speak their truth without others knowing what they said (step 13). Students appreciate the transparency of seeing a rubric for what they will be evaluated on (step 14).

All of these steps give students opportunities to make choices, take risks all while inspiring interest and motivation. They start to see why what they do in a group matters. This knowledge will serve them well for the rest of their lives. Knowing their peers will hold them accountable creates interest, engagement and informs their priorities.

Representation (What):

The steps in this process offer a variety of ways to present information in a group project setting. In my class, I use all of the following means of representation: student to material, student to self (thought and reflection), peer to peer, instructor to student, and, in my case, student to client. Methods of representation include: text and online readings, online assessment quiz, videos, graphics, examples, analysis, reflective writing, individual assignments and collaborative assignments, research reports, class discussion, student activities, oral presentations, written work and peer evaluations. These methods of representation can be modified and adjusted to fit any group project. Using various forms of material representation will likely ensure that students who learn in different ways are given multiple opportunities to learn the material and interact with the content, leading to retention, understanding and growth.

Action and Expression (How):

This method provides a variety of ways for students to express themselves. In my group project, they are working individually and collaboratively. They present their work in multiple forms: small group and full class discussion, writing, graphic representation and oral presentation. They are encouraged to come up with new and innovative ideas; something no one has ever thought of before. Students are able to do this due to the safe and collaborative environment we have created in the classroom by building strong relationships and reverence for respect. The instructor sets the tone and works to develop a healthy classroom where everyone is valued, feels safe to share ideas and are rewarded for “leaning in”.

Team members often become friends and support one another. Because they begin to care about each other, their interest and accountability increases. In the end, most of the students produce better quality work and feel much better about group projects than if they had not gone through this process. Allowing for various forms of expression allows students from different academic strengths to excel in ways that are best suited to their learning style, encouraging them to bring their strengths forward while others model areas they may like to improve on. Celebrating individual growth that is right for the learner in a supportive setting sets up a potential trajectory to continue with a growth mindset into their future.

Instructional Practice

Step 1: Best Groups Ever

EXPLANATION:When getting ready to introduce a group project to the class, I get students thinking about the great groups they have been a part of. I address the full class with this question: “What is the best group you have ever been in? It can be a school group, a social group, a work group – any group. For example, a sports team, band, church group, book club, friends group…any group that you belonged to that was a wonderful experience.” I give them a minute or two to reflect individually.

After a short time of reflection, I ask the class to turn to their neighbors and talk about the best groups they have ever participated in and share their stories with each other in small groups. The room comes alive with great conversation and excitement. I give the class 5-7 minutes (more if time allows) for this activity. Walking around the room during these discussions often reveals great insights into what makes group work great. When the allotted time is up, I call the class to order and ask students to share what made their “Best Group Ever” experience so great.

I move to the whiteboard and write “Best Group Ever” on one side of the board. Asking the class to give me some examples of what made their group experience great, students raise their hands and recall their experiences. I write down key words reflecting positive aspects of that experience, creating a big list as I go. Examples of keywords and phrases written on the board include: “respect, good communication, trust, being able to share ideas, feeling valued, dependable group members, etc.”

Once we have a long list of positive attributes, or, the answers start getting redundant, it’s time to move onto Step 2.

This first step gets students excited about the group experience as most everyone can recall a time they were part of a great group. It helps with motivation and is a building block to the 15 step process.

TROUBLESHOOTING: If you have an exceptionally quiet class that has a hard time sharing in a small group, you could start by giving an example of your own experience. I find that once people start sharing and telling stories, it prompts others to remember a time that they experienced a positive group scenario. Be sure to tell them this doesn’t have to be an academic or workgroup. They can share stories about friends, families, teams, bands and any social group they have been part of.

If the raising of hands takes too long or you are short on time, just have the students shout out words and phrases as you create a big list of positive phrases to add to the list. Sometimes I will paraphrase their words into a term that reflects what they are saying in the interest of time. If there are redundancies, I’ll point out an agreement with another term or maybe underline it for emphasis.

It’s important that you encourage students to share by reacting positively to their comments and by validating what they are saying.

SCHOLARSHIP: This step gets students talking to one another, assisting with socializing and creating interest in the topic. (Hernandez, 2002; Han & Newell, 2014; Hansen, 2006; Weibell, 2011)

Step 2: Worst Groups Ever

EXPLANATION: This step is similar to Step 1, but this time using the worst group experiences ever as a conversation piece. I ask the students to reflect on a time they were part of a bad group experience. Once again, I give them a minute or two to reflect on their personal experiences individually so they can recall some specifics about what happened. After a few moments, I ask them to share their stories with their neighbors in small groups. The room comes alive with animated recounts of how things went wrong and why it was such a bad experience. I give them another 5-7 minutes to share their stories with each other (you can adjust the time to fit your schedule).

When time is up, I break in and bring the class to order. Upon writing “Worst Groups Ever” on the other side of the whiteboard, I ask students to share their experience in the form of a word or short phrase that I list on the board. Examples of words and phrases are: “controlling, unresponsive, mean, late, unreliable, lazy, disrespectful, etc.” I continue to write words and phrases until they become redundant or we are running short on time.

This step really helps students by getting negativity and anxiety about group projects off their chests. It gets the elephant out of the room, so to speak, and allows us to have a conversation about times we’ve been in groups that have been stressful and unpleasant. This exercise helps us identify some of the behaviors that lead to poor group dynamics and unfavorable outcomes.

TROUBLESHOOTING: Most students enjoy this activity and won’t need a lot of prompting from the instructor. If you have a group that seems quiet, sometimes sharing your own experience can help them out of their shell. Also, asking probing questions might get them thinking, for example: “Think about a time you were uncomfortable in a group. What was going on that made you feel that way?”

SCHOLARSHIP: This step gets students talking to one another, assisting with socializing and creating interest in the topic. (Hernandez, 2002; Han & Newell, 2014; Hansen, 2006; Weibell, 2011)

Step 3: Importance of Collaboration

EXPLANATION: Once we have discussed the “Best Groups Ever” and the “Worst Groups Ever” and listed characteristics of each on the board, we discuss the importance of collaboration in the professional world as it relates to the discipline you are teaching. My profession (advertising/public relations) is a highly collaborative field where working with people in a variety of related roles is essential. I give examples and tell stories of why professionals in our field want to hire people who are high functioning team players. I explain that this is why it is important to focus on teamwork skills in the classroom. Once students understand that being a good team member will help them in their future, they are more motivated to work on developing these skills.

Pointing to the two lists we just created on the board (indicating “best team” and “worst team” behavior) I simply tell them to adopt the “Best Ever” group tendencies and avoid being “that person” with “Worst Ever” behaviors. This step is a pre-emptive move because it identifies counterproductive group behavior before it ever begins. No one has been given the chance to demonstrate the “bad group” behaviors because they have not started their group project assignment. Going through these first three steps before starting the project prepares students by helping them understand what is good and bad behavior in a group and begins to establish the class expectations for group work.

I also discuss the importance of both “task” and “social” aspects of a team. Teams are created for a reason, often linked to a task or outcome. It’s important to keep that goal in mind. Also, teams that create a positive social aspect are more likely to be accountable to one another, elevating their commitment and output. I encourage teams to socialize and have some fun together to create a bond that brings these benefits. Both “task” and “social” aspects are essential to groups.

Explaining that groups need people and people need groups is another dynamic of group behavior that I discuss with the students. Groups need people that bring something to the table. People need groups to serve their needs of belonging and reaching their potential. There is a symbiotic relationship that is often not examined. Once explained, students begin to understand the valuable aspects of teams.

In essence, this step helps motivate students and likely pre-empts poor group behavior before it even begins.

It is at this point I introduce the group project to the class.

TROUBLESHOOTING: You might take some time to reflect on how collaboration is important to your specific discipline. Provide examples of teamwork and collaboration you can share with your students. Consider studying up on what makes teams highly functional. There are some resources in the “Learn More” and “References and Resources” sections.

OPTIONAL ASSIGNMENT: To emphasize the value of collaboration in the student’s field of interest, I sometimes give the following assignment:

- Find a professional in your field

- Interview the professional on the importance of collaboration in their field

- Write a short paper on what you learned

- Report out the main points you learned in class.

SCHOLARSHIP: In order to increase motivation, students must understand why the topic is important and how it is relevant to them. This step helps them understand how they can benefit from honing their teamwork skills and why these skills are essential to their careers. (Hansen, R. 2006). This step is key to the Learning Process Methodology (Apple, D. et. al – see resources).

Step 4: Group Dynamics Homework

This is an important step to understanding group dynamics/communication/teamwork. I can tell them all I want, but until they read about best practices of group communication it doesn’t sink in fully.

EXPLANATION: After our discussion in class regarding various aspects of group dynamics, I assign homework that requires students to learn more about the topic. It is my opinion that we often thrust our students into team projects without ever teaching them about how to be successful in a group.

One of my go-to resources is this website: https://www.kent.ac.uk/ces/sk/teamwork.html

When assigning this homework, I pull up this site in class and point out some of the more important aspects. There are many links and deep dives that provide extensive information. I point out the manadory material they must review on the website and encourage them to explore more than required.

TROUBLESHOOTING: There are many resources available on this topic so you can choose what works for you. I’ve included some suggestions in “Learn More” and “References and Resources”. It’s a good idea to become familiar with the content of what you are assigning, so be sure to read through the material so you can field questions and comments.

SCHOLARSHIP: This step is essential for students to learn about and understand group dynamics, group communication, roles people play in groups and how to be more effective in a group as well as behaviors to avoid. (Hernandez, 2002; Hansen, 2006).

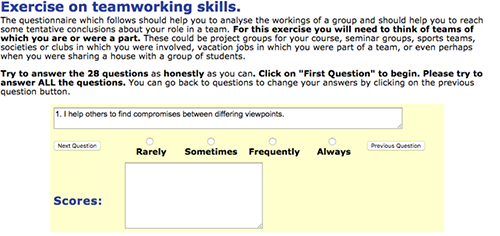

Step 5: Self-Assessment

EXPLANATION:One of the great things about the website I use for group dynamics homework as presented in Step 4 is that the site has a short selfassessment component. I assign students this quick 28 question “quiz” that identifies some of their tendencies and roles they may play in groups. Though it is not always completely accurate being the “quick and dirty” test that it is, it often highlights some behavioral aspects that students can relate to. This tool gives students a score on a variety of team roles, showing them where they may be the strongest and areas they may want to improve.

Here’s a snapshot of the assessment tool:

Figure 1: A snapshot of the assessment tool, click for larger image.

TROUBLESHOOTING: This self-assessment, or any self-assessment, may not completely define an individual accurately. Generally speaking, most students find it pretty close to true for them. Once in a while, a student will disagree with the outcome of their score. It doesn’t really matter. What matters is, they are learning about roles and the fact that people often have strengths in one area and weaknesses in others. I explain that a more comprehensive test, like a Myers Briggs or StrengthsQuest, would be more accurate. They are also more lengthy and often cost money. I encourage students to explore these tests if they are interested. For our purposes, the short assessment on the University of Kent site works fine.

SCHOLARSHIP: This step fits well with the Learning Process Methodology (LPM) which stresses reflection as a tool for deeper learning. (See resources for more on LPM). It also reinforces the benefits of diverse team members. This enlightenment informs team selection. (Hernandez, 2002;Hansen, 2006).

Step 6: Self-Reflection

EXPLANATION:After reading about group dynamics and taking the self assessment, I require students to write a 1-2 page a self-reflection paper. This forces students to think about what they read regarding group dynamics and reflect on their own experiences in groups. The reflection is often an eye opener for students as they see the various forces at play that made their previous group experiences positive or negative. As learners reflect on their role in groups they’ve participated in, they often become aware of how they could be more productive. This self-reflection paper frequently reveals revelations and new resolutions as students grow and learn about teamwork. This exercise helps solidify student commitment to positive team behavior. Students seem to like this assignment and most times I can really see the “light bulb turn on” as they begin to understand how to improve group dynamics and how this information can be useful to them.

I have included an example of my Self-Reflection assignment in “Learn More” and “References and Resources“.

TROUBLESHOOTING: There are times when students don’t dig deep enough to come to any meaningful insights, however, in my experience, these students are in the minority. Sometimes students will write about the fact that they knew this all along. That’s ok. It’s still a useful exercise and the reflection still reinforces good group behavior.

SCHOLARSHIP: This step also fits well with the Learning Process Methodology (LPM) which stresses reflection as a tool for deeper learning and insight moving forward, creating motivation. (See resources for more on LPM). It also reinforces the benefits of diverse team members. This enlightenment informs team selection. (Hernandez, 2002;Hansen, 2006).

Step 7: Bring Assessment Scores

EXPLANATION: I ask students to bring their self-assessment scores to class the next time we meet. This serves a couple of purposes: 1) It holds them accountable for completing the assessment, and 2) It opens the conversation that we are about to have in class.

After doing the group dynamic reading, self-assessment and reflection, we discuss the important points in class. I will hold an interactive conversation about the most important points, most surprising points, most useful points that they learned about group dynamics. We discuss the various roles people play in groups and make a note about negative roles that can sabotage a project. The students often come with some revelations they want to share and typically the conversation is lively.

I also use these scores as a networking prompt forStep 8: Class Networking.

TROUBLESHOOTING: If the students are reluctant to share their thoughts with the entire class, they may be more comfortable talking in small groups about what they learned and what their strengths are. You can easily turn this open class conversation into a “think-pair-share” exercise or small group discussion. (Note: Think-pair-share is a method that helps students reflect individually on a question/problem first (think); discuss their ideas with a neighbor (pair) and finally report out to the entire class during discussion (share). I find it’s much easier to get students to share their thoughts if I give them the opportunity to think and pair before they share.)

SCHOLARSHIP: This step also reinforces the benefits of diverse team members. This enlightenment informs team selection. (Hernandez, 2002;Hansen, 2006).

Step 8: Class Networking

EXPLANATION: As we prepare to group the class into teams for their project, I discuss the benefits of a diverse group. Explaining that it is human nature to want to group with like people, it’s often more beneficial to group with people different from yourself. It’s smart to have a variety of talent and perspectives on your team. I often cite research to back this up (Abreu, 2014;Goleman, 2018;Grillo, 2015;Hewlett, Marshall & Sherbin, 2013;Larson, 2017;Phillips, 2014;Rock & Grant, 2016.) and discuss the idea that you want people on your team who are strong where you might be weak. For this reason, I have them hang on to their self-assessment scores as we go into a class networking exercise.

Because people tend to talk to those they sit near the most, they may miss out on meeting classmates that could be beneficial to their team. So, I have the students get on their feet for some meet and greet exercises. I announce that we are going to network, not unlike meeting someone in a forced social setting. I give them these instructions before we start the icebreakers:

- Try to talk to people you have never talked to in class before.

- Try to meet as many new people as possible.

- I will give you instructions on what to do. When you find your group, introduce yourself and talk about what you feel you can contribute to a group. Your self-assessment sheets can help prompt these conversations.

- Continue to listen to my instructions periodically throughout the networking process and continue to introduce yourself and talk about your strengths.

- Have a little fun with this exercise!

You can use any type of mixer/icebreaker exercises, but these are some that I tend to use:

- Find people with the same/similar color shirt. Get in a group and talk for about 5 minutes. (Call them to attention and introduce the next icebreaker)

- Group together with people who have the same birth month as you. Get in a group and talk for 5 minutes. (Call them to attention and introduce the next icebreaker. Remind them to continue to talk about their strengths and meet more new people if possible.)

- Gather with people who have the same favorite (ice cream, advertising mascot/slogan, song/move genre etc.) as you. Talk for 5 minutes.

During the icebreakers, wander through the groups and keep an eye out for anyone who needs support. Do your best to help them integrate.

The idea behind this exercise is the get students out of their comfort zone, meet new classmates and try to identify people who might complement their own skill set for their team. At this point, the room has come alive and the students are enjoying being able to socialize in class.

TROUBLESHOOTING: Sometimes there are students that are quite introverted (or unmotivated) and they have a hard time getting started with this exercise. Keep an eye out for these students and quietly help them work through this process. Sometimes, I’ll accompany the more reluctant students until they feel more comfortable. That usually just takes finding a friendly face to introduce them to.

Once the groups get talking, it can be a challenge to get them to listen to switch gears to the next grouping. Be prepared to project your voice as you break into their conversations. It may be a good idea to have a timer, bell or visual countdown on a screen to keep them on track.

SCHOLARSHIP: Too often, students don’t have the opportunity to meet everyone in the class and find out what their “superpowers” are. This step assists with socialization, learning more about others, giving an opportunity to meet students that may have different strengths and increases likelihood that teams seek diversified talents. It also increases interest, engagement, ownership, incentive, motivation, empowerment while creating an inviting learning environment. (Hernandez, 2002;Han & Newell, 2014;Hansen, 2006;Weibell, 2011).

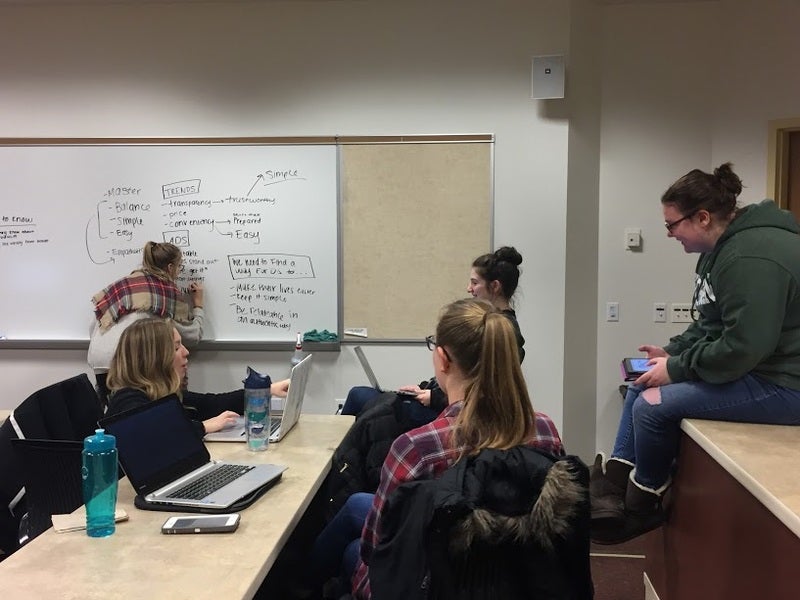

Step 9: Group Selection

EXPLANATION: After the students have had a chance to get to know more people in class through the networking exercises, I announce we will start forming teams for their group project. Knowing that students are happier, more motivated and more productive when they have a voice in this process, I use an “assisted” self-selection process. This means students self-select groups based on insights from class discussion, reading, homework, reflection, and networking. After giving them parameters (such as no more than 5, no less than 3 to a group) and reminding them it’s important to have a diverse skill set on each team, I give them time to self-select their teams. When I see students needing a little help with this process, I “assist” them by accompanying them through this process and helping them find an agreeable group.

Once groups are selected, I ask them to sit down together with their team. I explain that these groups are not set in stone quite yet and teams can exchange members, or I can move people around if I see a need to do so within a one week period. This allows me to: (a) integrate students who were absent for the selection process; (b) help students who need assistance finding the right team; (c) adjust groups according to needs such as schedule conflicts, special skills etc. and; (d) allows students to contact me outside of class if they are feeling uncomfortable with their group and provides a window to make adjustments if needed.

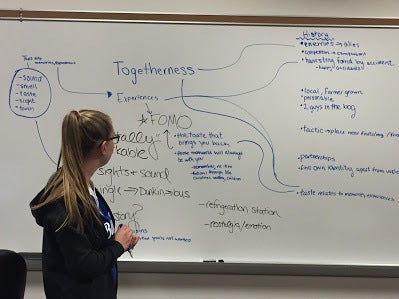

Figure 2: A group of students work together on a problem at the whiteboard

I find that students feel empowered through this process and in most cases, the original teams remain intact. The teams form closer bonds and are happier than if they were arbitrarily placed together by the instructor. This increases accountability and output.

TROUBLESHOOTING: Admittedly, this process can be stressful for some students, especially introverts. Sometimes students prefer to be placed in a team by the instructor rather than going through this process. It is fairly easy to spot the students that need a little extra help if you are closely monitoring the process by walking through the interactions and listening to the students. Often, if a student needs help, they will ask you for it. Or, you’ll be able to spot an anxious student. I think it’s best to encourage the apprehensive student to try the process first (i.e. get in there and talk to the other students). If they just can’t, then ask some questions, like, what are your strengths and what other strengths do you want on your team? I can often lead them to a group that needs their skills. As a last resort, I will simply place them in a group that seems like the right fit.

It’s easy to feel a little anxious yourself while this process is taking place. It can be a little chaotic and it’s easy to move in too quickly. I advise instructors to hang back and let the students work it out. In the end, I often hear words of thanks for letting them choose their own groups.

Additionally, I always leave the door open for switching groups within the first week for reasons stated above. Sometimes, a student will come to me privately with an issue that I may not be aware of. By announcing in class that teams are fluid for one week, students don’t feel stuck and know we can make adjustments if needed, which also gives them some relief.

SCHOLARSHIP: The jury is out on whether groups should be formed by instructors or by students. Actually, there are pros and cons to both (Hansen, 2006). This process combines student/instructor chosen groups by initially letting students choose their groups pending approval by the professor. I find this increases interest, engagement, ownership, motivation, empowerment, commitment, self-efficacy and satisfaction while creating an inviting learning environment. (Hernandez, 2002;Han & Newell, 2014;Hansen, 2006;Weibell, 2011).

Step 10: Team Expectations Agreement

EXPLANATION: Once the teams are chosen, I ask them to sit together for the rest of the semester. I hand each team a “Team Expectations Agreement” that gives them some direction but is left open for them to discuss and create. One of their first tasks is to exchange contact information, generate a team name and discuss their expectations for their group. Expectations include guidelines for group behavior, communication methods, agreements on tasks, roles, deadlines, etc. The expectations should be reasonable and achievable. For example, instead of saying, “we will get an A on our project”, they might agree to weekly check-ins, set and meet deadlines, ask for help if needed, and answer team communications within 12 hours. I explain that these expectations come from them, not me, and they should work these ideas out before they start the project.

I give them time in class to discuss their expectations and give them a full week to fill out their “Team Expectations Agreement” before handing it in to me. For my class project, students are creating an advertising campaign for a real client. On their “Team Expectations Agreement” I ask them to list the following: (1) Team Member Names; (2) Team Name (or Ad Agency name in my case); (3) Client Name (I often have multiple clients) and; (4) Expectation Statements. Each team member also keeps a copy.

This process helps teams talk through potential problems that have not had a chance to develop. Because we have taken the time to learn what makes a group effective and what behaviors can derail a group, students are fairly eager to sort this all out up front. They are recalling their “worst team ever” and work to avert those behaviors. I find that students have a sense of relief that they are able to agree on these expectations in advance, clearing the way for a productive team project.

(See the example of Team Expectation Agreement in “Learn More“.)

TROUBLESHOOTING: Sometimes students have a difficult time thinking of expectations to include in their agreement. That’s okay. That’s why I give them a week to think about it and time in a couple of classes to discuss. I encourage them to share their ideas with other teams to get more ideas. This document serves as a contract between team members and makes members less likely to deviate from expectations. This nips problems in the bud before they ever happen. Should a team start to struggle, the first thing I have them do is pull out this agreement and ask them to refresh their commitment to the team expectations to try to get back on track. Of course, there can be unanticipated problems when people work in teams. However, this exercise seems to cut down on those issues considerably.

SCHOLARSHIP: There are many examples of team contracts and expectations agreements. I have adapted mine fromOakley, Felder, Brent & Elhajj, 2004. (Seereferences and resources.)

Step 11: Group Project Evaluation Policy

EXPLANATION: Some of the more common complaints I hear about group projects focus on the grading aspect. Often instructors assign one grade to the entire group and that’s that. This creates frustration and anxiety for students who are diligent about their grades and worry about a low performing group member dragging their grade down. This feels unfair to them and can cause unintended consequences in the group. For example, the stronger students may take control of the project and the low effort students will sit back and let it happen, creating an imbalance in the group from the start. To mitigate this issue, I have created the “group project evaluation policy”. (Steps 11-15 also assist with this issue.)

I explain my “group project evaluation policy” at the start of the project so everyone understands how they will be evaluated. In a nutshell, teams will be evaluated on the outcome of their project as a whole. Additionally, I work to understand how each individual contributed to the project so I can assess if individual grades need to be adjusted. If the group functions well as a whole and each individual does their due diligence, they all get the same grade. If the team was off balance in effort, I will adjust individual grades up or down accordingly.

In addition to explaining the policy to the class at the outset of the project, I also post the written policy on our class management system, BlackBoard. You can find an example of my policy in “Learn More.”

TROUBLESHOOTING: Creating and explaining a group project evaluation policy up front heads off problems down the line and provides transparency on how students will be graded. This is beneficial to everyone, students and instructors alike. Addressing the grading component before the project starts can avert problems before they begin. Students are clear on the evaluation process and understand they will be individually accountable. This helps to keep each student engaged throughout the entire process which elevates group work. It also deters complaints at the end of the semester, which is helpful for the instructor.

SCHOLARSHIP: Knowing how work will be evaluated is essential for individuals to be motivated to perform well in teams. (Hernandez, 2002;Han & Newell, 2014;Hansen, 2006).

Step 12: Individual Assignments that Feed into Group Assignments

EXPLANATION: I require that each student complete certain assignments individually first, then they share their work with the group. This holds every student accountable and keeps them learning on an individual basis. The added value is, when each student brings their individual ideas to the group, the team has more content to work with to find the best solution. It also avoids Group Think. The team discusses each idea or approach, choosing the best aspects of the ideas, ideally crafting a new combination of ideas to best fit their mission. Because there is no one correct answer with the project I assign (an advertising campaign) this process usually raises the bar by integrating many ideas into the mix. Most times, teams come up with better ideas when they have more to work with.

Figure 3: A student works on an individual assignment at the whiteboard.

Additionally, this step allows me to assess work from each student individually so I have a clear picture of the quality of each student’s work apart from the team as a whole. It’s also helpful to the students because they get direct feedback from me on what they are doing well and what they can improve on. I find this step essential to heightened group performance and issuing a fair grade.

You can see an example of my Individual Assignments in “Learn More“.

TROUBLESHOOTING: Yes, this step creates more grading for the instructor. However, the benefits outweigh the burden. The students are held accountable, learn more, and perform better. As an instructor, you know exactly how each student is performing and you are able to clearly justify your grading. My suggestion would be to try to keep up with grading and individual feedback in a timely fashion.

SCHOLARSHIP: Individual accountability is essential for teams to operate optimally. (Hernandez, 2002;Han & Newell, 2014; Hansen, 2006).

Step 13: Personal Assessment Letter

EXPLANATION: I require that each student writes a “personal assessment letter” about their group process and the performance levels of each team member. This is a private communication that is handed directly to me. They are to address the following items honestly and succinctly: (a) their group process; (b) lessons learned, and; (c) each team members efforts including their own. With the understanding that no one else will see the letter, the comments become honest and revealing. These insights, along with my own observations, help me determine appropriate grades for each student.

This idea was an outgrowth of frustration after having teams assess each other on a Likert type scale. I noticed that the majority of students gave every member of the team a high grade. I came to understand that once you hand out a Likert scale type evaluation, someone on the team will suggest they all just give the highest rating to everyone thinking this will raise the team score. When teams assess one another in the presence of each other, they are not likely to call one other out. The reality is, my former method of a Likert scale assessment in class was not a true measure of what really happened in the group. Having to write an assessment in their own words, in private, and handing their notes directly to me without the possibility of their team members seeing their comments, has made a big difference in the assessment feedback.

TROUBLESHOOTING: This step is easy for students to forget when the rest of their project is due at the same time. Be sure to remind students to do it and reiterate that this is worth points. Stressing honesty and privacy is also important. It’s quite revealing when you read each individual letter within the context of the team. Some students will still portray that everything was great, however, the truth is shown through the consistencies or inconsistencies of the letters. If there is a red flag, this gives you the opportunity to call the student in for a conversation face to face about what really happened. Once in a while, just this assignment will prompt some visits to your office for conversations about what “really” went on in the group. Again, this opens the door to further conversations and resolutions you might consider.

SCHOLARSHIP: This step is also in line with Learning Process Methodology (LPM) stressing reflection as a learning opportunity (seereferences and resources). Personal Assessment Letters are actually peer evaluations and are advocated by a variety of scholars for accountability (Hernandez, 2002;Han & Newell, 2014;Hansen, 2006).

Step 14: Rubrics

EXPLANATION: Rubrics are an important piece of the group project process because they reveal how students will be graded. My rubrics are designed to give guidelines on assignment components, yet, allow for a wide variety of approaches to meet the objectives of the project. I will go over the rubrics in class, give explanations and entertain questions. Then, I post the rubrics on our class management site so students can refer to them early and often. Students appreciate the transparency and guideposts of rubrics that keep them on track and focused on the most important aspects of the assignment.

TROUBLESHOOTING: When designing a rubric, be sure it aligns with what your assignment is asking them to do. In fact, I use my assignment to create the rubric. I prefer to keep rubrics fairly open rather than rigid so that a number of solutions can apply. To be honest, I have a bit of cognitive dissonance regarding rubrics. I dislike “teaching to the test” and feel that students don’t garner deep learning by simply memorizing information. However, my assignments have no one right answer, so there is no memorization involved, rather research, critical thinking and problemsolving are key. Rubrics in this case not only help students focus on valuable aspects of the assignment, but they also help the instructor stay consistent in his/her grading.

SCHOLARSHIP: There are various schools of thought on the use of rubrics. For more on this topic, seeReddy & Andrade (2009)inreferences.

Step 15: Outputs and Evaluations

EXPLANATION: Each group project is different, however, each project has a purposeful goal, objective, or output. Whatever that end result or product is, it will have to be evaluated. Evaluation of the output completes the process. It is important to be clear on what the objective is and what the output from the group project should strive for.

For example, in my advertising campaign group project, teams have three components, or outputs, due to me at the end of the project: (a) giving an oral presentation as a team; (b) producing a written component of their work, and; (c) writing an assessment in the form of a personal letter to me. Each of these outputs has specific criteria that I include in the assignment, discuss with them in class, and post on our course management site.

As for evaluations, I believe that hearing from multiple sources assessing their work is a valuable learning and growing tool for the student. Therefore, in addition to my own assessment of their outputs, I also incorporate “peer” assessments from classmates as well as client feedback when we have real clients we are working for. Hearing how their peers and clients assess their presentations adds value to my own assessment. All feedback from peers and clients are reviewed by me and are considered when I develop their final grade. Feedback from their professor, peers, and clients provides students with valuable critiques that most of them appreciate, learn, and grow from.

TROUBLESHOOTING: Peer evaluators and clients may not know what to look for in evaluating an output/presentation. Therefore, I create rubrics to provide to each assessor. This helps evaluators know what to look for and also keeps assessments consistent. It’s important to ask both peer evaluators and clients to not only rate the teams on a Likert scale that I provide, but, to also write their own comments about the project overall. Specifically, I ask all evaluators to write down three things: (a) what they liked the most; (b) what could be improved upon, and; (c) any other comments the team would find helpful.

Including assessments from student peers and clients is beneficial for the student being evaluated as well as the instructor. Sometimes, they focus on a point I missed or bring up a new angle. I value these types of evaluations and consider them in my grading when valid. In the end, having others beyond the instructor weigh in on student work adds credibility to the work and grade.

SCHOLARSHIP: The need for developing excellent oral, written, and interpersonal communication skills is essential for students. Practicing and honing these skills via group projects and team-based learning is vital for success post-graduation. Assessment from professors, peers, self and other constituents, such as clients or community members, are essential for growth and lines up with Learning Process Methodology (LPM) and other scholars (Hernandez, 2002; Han & Newell, 2014; Hansen, 2006).

Results:

![]()

The majority of teams that go through this process have a positive experience and an increased appreciation for group projects. Students often thank me for taking the time to: (a) help them learn about successful group dynamics; (b) furnish guidelines to keep them on track; (c) provide transparency on how they will be graded; (d) protect them from grade deflation when a team member loafs; (e) equip them with tools to develop their collaborative skills; (f) provide them with multiple sources of feedback, and; (g) provide them with a valuable project they can add to their portfolio.

Timing: It’s important to note that these steps take place throughout the entire group project process, beginning, middle, end. Every group project is different and the timeframes for projects vary. These steps are designed to adapt to any project. You can use them all or integrate just the steps that are most useful to you. The timing is your call. I believe you will naturally find a rhythm of how and when to use the steps you choose to integrate into your own successful group project. Don’t be afraid to adapt or try new ideas. Sometimes, I just come clean with the students and tell them I’m trying something new. I find that students respect honesty and authenticity and may even encourage them to try something new, too.

More on Timing: My group projects range anywhere from 6-30 weeks, depending on the situation. For a 15 week semester with a 10-week project, I would incorporate steps 1-3 in the class session the previews the actual project. Steps 4-6 are homework assigned the day you complete steps 1-3.

Steps 7-10 Take place the following class session, though I allow extra time for step 10, typically giving them a full week to work on this agreement.

Steps 11-12 are explained at the same time I introduce that actual project they will be working on.

Steps 13-14 are explained once the project is underway.

Step 15 is part of the evaluation process at the end of the project.

Learn More

Group Dynamics Resources

https://www.kent.ac.uk/ces/sk/teamwork.html

http://www.strengthsquest.com/home.aspx

https://www.myersbriggs.org/my-mbti-personality-type/mbti-basics/home.htm?bhcp=1

http://www.humanmetrics.com/cgi-win/jtypes2.asp

15 Steps to Group Project Success Graphic

Example Documents

- CAP 210 Group Campaign Rubric W16.pdf

- CAP 210 Grading Individual Campaign Assignments-1.pdf

- Group Project Evaluation Policy.pdf

- Individual Assignments Feed Into Group Assignment.pdf

- Peer Evaluation.pdf

- Personal Letter.pdf

- Self-Reflection Paper – Group Dynamics.pdf

References & Resources

Abreu, K. (2014, December 9). The myriad of benefits of diversity in the workplace. Retrieved fromhttps://www.entrepreneur.com/article/240550

Goleman, D. (2018, March 5). Diversity + emotional intelligence = more success. Retrieved fromhttps://www.kornferry.com/institute/diversity-emotional-intelligence-leadership

Grillo, G. (2015, April 23). The advertising industry needs diverse leadership to thrive. Ad Age. Retrieved fromhttp://adage.com/article/agency-viewpoint/advertising-industry-diverse-leadership-thrive/297998/

Han, G.K. & Newell, J. (2014). Enhancing student learning in knowledge-based courses: Integrating team-based learning in mass communication theory classes.Journalism & Mass Communication Editor,(69)2, 180-196.

Hansen, R.S. (2006). Benefits and problems with student teams: Suggestions for improving team projects.Journal of Education for Business,82(1), 11-19.

DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.82.1.11 19

Hernandez, S. (2002). Team learning in a marketing principles course: Cooperative structures that facilitate active learning and higher level thinking.Journal of Marketing Education,1(1), 73-85.

Hewlett, S., Marshall, M., & Sherbin, L. (2013, December). How diversity can drive innovation. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved fromhttps://hbr.org/topic/innovation

Larson, E. (2017, September 21). New research: Diversity + inclusion = better decision making at work. Forbes. Retrieved fromhttps://www.forbes.com/sites/eriklarson/2017/09/21/new-research-diversity-inclusion-better-decision-making-at-work/#15e756cb4cbf

Phillips, K. W. (2014, October 1). How diversity makes us smarter. Scientific American. Retrieved fromhttps://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-diversity-makes-us-smarter/

Oakley, I.B., Felder, R.M., Brent, R., & Elhajj, I. (2004). Turning student groups into effective teams. J.Student Centered Learning,2(1), 9–34 (2004). Retrived fromhttps://www.engr.uvic.ca/~mech464/MECH464_TeamPoliciesAndExpectationsAgreeme nt.pdf

Reddy, Y.M. & Andrade, H. (2009). A review of rubric use in higher education.Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education,35(4), 435-448.

DOI: 10.1080/02602930902862859

Rock, D., & Grant, H. (2016, November 4). Why diverse teams are smarter. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved fromhttps://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter

Weibell, C. J. (2011).Principles of learning: 7 principles to guide personalized, student centered learning in the technology-enhanced, blended learning environment. Retrieved July 4, 2011 from [https://principlesoflearning.wordpress.com].https://principlesoflearning.wordpress.com/dissertation/chapter-3-literature-review-2/the human-perspective/freedom-to-learn-rogers-1969/

Additional Resources

IDEO

https://www.ideo.com/

(Great inspiration on how to collaborate to solve problems)

IDEO Shopping Cart Challenge

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M66ZU2PCIcM

(Case study on how collaboration can bring innovation)

Learning Process Methodology (Apple, D. et al) Leise, C.; Beyerlein, S. & Apple, D. (n.d.)Pacific Crest Faculty Development Series.http://www.pcrest.com/research/2_3_8%20%20Learning%20Process%20Methodology.pdf

Nancarrow, C. Profile of a Quality Learner1.2.2 Profile of a Quality Learner – Faculty Guidebook

Team Expectations Agreement

Oakley, I.B.; Felder, R.M.; Brent, R. & Elhajj, I. (2004). Turning student groups into effective teams. J.Student Centered Learning,2(1), 9–34 (2004).https://www.engr.uvic.ca/~mech464/MECH464_TeamPoliciesAndExpectationsAgreement.pdf

Skillman, Peter Ted Talk Marshmallow Challenge

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1p5sBzMtB3Q

(This is a great team work exercise that helps build camaraderie and social glue in a group).

Wujec, Tom: Build a tower, build a team

https://www.ted.com/talks/tom_wujec_build_a_tower#t-11476

University of Kent. (n.d.). Team Working Skills.The U.K.’s European University.https://www.kent.ac.uk/careers/sk/teamwork.htm

(I use this site for Group Dynamics and Team Work homework and self-assessment.)

Authors of Inspiration:

Apple, Dan (Learning Process Methodology, etc.)

Bain, Ken (What the best college teachers do)

Brown, Brene’ (Daring Greatly)

Csikzentmihaly, Mihaly (Creativity and the psychology of discovery and invention, etc.)

Goleman, D. (Working with Emotional Intelligence, etc.)

Pink, Daniel (on motivation)

Rogers, Carl (Freedom to learn, etc.)

More Articles of Inspiration:

Apple, Daniel. (2016). Key learner characteristics for academic success.International Journal of Process Education. V8. 61-82.

Apple, D., Ellis, W. & Hintze, D. (2016). 25 years of process education.International Journal of Process Education.8(1). p.111http://www.ijpe.online//2016/color033116sm.pdf#%5B%7B%22num%22%3A5%2C%22gen%22%3A0%7D%2C%7B%22name%22%3A%22FitR%22%7D%2C-42%2C286%2C654%2C792%5D

Apple, D. & Ellis, W. (2015). Learning how to learn: Improving the performance of learning.International Journal of Process Education.1(1), 21-217.

Apple, D. K. (2000).Learning assessment journal. Lisle, IL: Pacific Crest.

Erikson, M. G. (2017).Students as adults. Academic Questions,30(2), 237-240.

doi:http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.gvsu.edu/10.1007/s12129-017-9628-6

Motschnig-Pitrik, R. & Holzinger, A. (2002). Student-centered teaching meets new media: Concept and case study.Journal of Educational Technology & Society,5(4). 160-172. Retrieved fromhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.5.4.160

Rogers, C.R. (1970). Freedom to Learn.Journal of Extension.(8)1. Columbus, Ohio: Charles E. Merrill Publishing Company, p. 358.

Rogers, C. (1958). Personal thoughts on teaching and learning.Improving College and University Teaching,6(1), 4-5. Retrieved fromhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/27561843

Rogers, C. R. (1961). On Becoming A Person – A Psychotherapists View of Psychotherapy. Ch. 14 & 15.

Rogers, C. R. & Freiberg, H. J. (1994). Freedom to Learn, 3rd edition, Columbus: Charles E. Merrill Publishing Co.

Wellins, R. S., Byham, W. C., & Wilson, J. M. (1991).Empowered teams: Creating self-directed work groups that improve quality, productivity, and participation (1st ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

About the Author

Robin Spring

Associate Professor, Advertising/Public Relations

The School of Communications

Grand Valley State University

Growing up in a family of educators inspired a love of lifelong learning and teaching in Professor Spring. Her professional work in radio, television, print and agency provide her with multi-faceted experiences in advertising and public relations. Spring’s professional work has taken her from Michigan, to the U.S. Virgin Islands and Texas then back again. Practical knowledge of client relations, strategic planning, creative campaigns, copywriting, sponsorships, partnerships, special events, celebrity promotions, media relations, sales, fundraising, and integrated marketing communications in various cultures and professional teams translate well in the Ad/PR courses she teaches.

Professor Spring serves as Faculty Advisor to GVSU’s Student Advertising Club and Faculty Advisor to GVSU’s National Student Advertising Competition (NSAC) team. She serves on the board of American Advertising Federation of West Michigan (AAFWMI) a.k.a. “Ad Fed” as Student Initiatives Director. Professor Spring also serves on the Association for Educators in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC) Advertising Division as Teaching and Pedagogy Chair.

Professor Spring’s research interests include advertising education, diversity, creativity, teamwork, and the scholarship of teaching and learning.

Teaches

Undergraduate courses in Advertising/Public Relations/Integrated and Strategic Communications

Currently: Research Basics for Advertising and Public Relations, Fundamentals of Advertising, Advertising Copywriting, Advertising/Public Relations Campaign

Previously: Concepts of Communication, Critical Interpretation, Interpersonal Communication, Nonverbal Communication, Speech, Story Making and Writing Corporate Communication.

Degrees

B.S., Advertising & Public Relations, Grand Valley State University; M.S., Communication, Grand Valley State University.