Advance Organizers: Preparing Students for Learning

Contents

Introduction

Faculty members are often in search of methods for presenting content that are beneficial in helping different types of college students learn. One approach, the Advance Organizer, is a visual organization practice which can be used at the beginning of a class or a new unit of study to present new information to students. It can also set the stage for building on existing knowledge from prior learning. This type of organizer has a dual purpose to help students prepare for class by providing an overview of what will be discussed and then provide more detailed insight into the material as it is taught; facilitating the ability for students to make connections between the main ideas and supplementary content throughout each class period or unit of study.

UDL Alignment

Each College STAR module will explain how a particular instructional practice described within the module aligns with one or more of the principles of UDL. For this module, the focus will be on Principle III, Provide Multiple Means of Engagement.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Engagement

Advance Organizers are a visual organization practice which can be used at the beginning of a class or a new unit of study to provide a framework for now new information will be presented during the lesson/s. Advance Organizers have been used to increase engagement in the college classroom by encouraging students to listen attentively while actively engaging in some form of note taking process. (Bohay, 2011) This type of instructional routine not only provides a pre-class planning opportunity but also aids in priming student background knowledge. Organizers offer a tool for educational scaffolding and can provide a variety of note taking techniques used to move students progressively toward stronger understanding and greater independence in the learning process. Additionally, Advance Organizers can be used to facilitate active learning, something that increases student performance in test taking and concept application.

Instructional Practice

Getting Started

Advance Organizers provide an organizational framework that instructors develop prior to presenting information to students. This framework prepares students for what they are about to learn and can help provide links between new ideas and similar concepts. Advance Organizers help instructors and students focus on information that is important and essential. The format of Advance Organizers can be very basic or visually creative and will depend on the instructor style, the material to be learned, and the learner’s characteristics. The methods for presenting information to students will also influence the design of the organizer. For example, an organizer for an online class may be different from one used in a face to face classroom. (Mayer, 1979)

Dr. David Ausubel, one of the early advocates for use of Advance Organizers in the 1960’s, believed that when students use Advance Organizers, they can bridge the gap between learning new information and information they already know (previously existing schema into new schema). His approach was to use broad concept categories to help students organize new pieces of information and tie the new information to an existing organizational structure, resulting in retention of new information. “With the use of an advance organizer, new material will be rendered as more familiar and meaningful, as learners will have an organized structure in place to store new ideas, information, and concepts.” (Allen, 2014) In short, this kind of structure makes transparent for students the back-thinking and connections that instructors use to plan what new information should be taught from class to class, thus taking the guesswork out of making these connections for students and potentially deepening student understanding of the new material.

Advance Organizers are more than just graphic organizers, but can take many forms as long as they serve the goal of helping students know what to expect and make important connections with content. Two key types of Advance Organizers will be addressed in this module – Expository and Comparative, along with two organizational subcategories which will be explained in more detail in the Styles of Advance Organizers section.

An Expository Organizer can be used when material will be presented that is unfamiliar or new to students. For example, when an instructor presents a new lesson on a topic that has never been discussed and helps students make connections to what they may already know. It can be presented graphically or verbally and is highly effective when used at the start of a unit. Studies support a high rate of student success when organizers are presented before new material, the organizer is neatly displayed using pictures or text, and the organizer provides an example that shows a relationship between the organizer and the new material. (Corkill, 1992)

A Comparative Organizer is presented when material is relatively familiar or when new ideas will be integrated with prior knowledge. For example, if a student learns about the Windows® operating system, and new information is given about the Mac® operating system, the student will be able to compare and contrast to understand the differences, thus integrating existing knowledge with new knowledge.

The Many Styles of Advance Organizers

Regardless of whether they are Expository and Comparative, Advance Organizers can take many forms. For this module, we will use the broad categories of text organizers, graphic organizers, and narrative organizer practices. While these organizers are not the only formats available, they are the most widely used. The Advance Organizer can take on any of the categories mentioned above or use them in combination.

Text Organizers

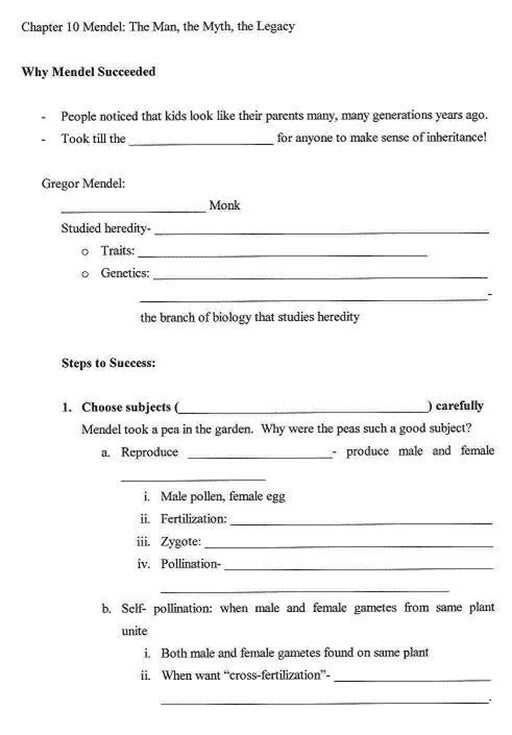

Text Organizers can consist of guided notes (see image below), verbal directions, or pre-questioning techniques. Text organizers can assist students while taking notes during the presentation of lecture material. These organizers reduce the quantity of information students must write, but keep students engaged in the lesson by requiring some active note taking. The notes create an outline for students that not only reduce writing demands, but also makes clear the organization of ideas for a lesson. Students in any given class will process information being presented in a lesson at differing speeds. This technique makes it more likely that all students will leave class with the necessary information and connections to master and apply the new material – not just those students who process auditory information quickly. Students who have difficulties with fine motor tasks can benefit by even more explicit notes that contain shorter blanks or choices to circle. (Konrad, 2010)

Outlines and PowerPoint slides (when an electronic or hard copy is given to the students prior to the lesson) also fall into the category of text organizers providing students with a structured guide for filling in appropriate information, and time to also add in pertinent examples and information from class discussions (as they are not spending all of their time trying to record just the most basic information). When instructors give guided notes with in-class review time, learning can be enhanced. (Konrad, 2010) Pre-questioning techniques can be used to provide hints and clues about what will be taught as well as activate background knowledge and aid students in the process of filling in missing information. (Helterbrand, 2012) Additionally, students who use pre-questioning organizers benefit from the detailed information provided in an organized fashion when having to draw conclusions (Larson, 2009).

Dr. Derrick Wirtz, a Psychology professor at ECU, currently uses Advance Organizers and has been since he was a graduate student. Dr. Wirtz provides students with an outline organizer text organizer which follows his PowerPoint slides. He wants his students to have access to course material in advance via instructional technology like Blackboard so they can print the notes and use them during class. Dr. Wirtz shares that this model helps support his student’s note-taking and make the class a more flexible and engaging environment.

Tiffany Woodward, a Management instructor in the College of Business at ECU, shares her experience using Advance Organizers as a way of easing the strain of taking notes during class. Ms. Woodward provides PowerPoint materials before class on her Blackboard site to accommodate her student’s needs. Ms. Woodward understands the difference between learning styles and wants to give her students every opportunity to be successful in her course. Providing materials before class gives her students ample time to browse and gain understanding of course concepts which are later applied during class activities which reinforce learning.

Figure 1: A document set up for guided notes in the form of fill in the blank pre-questioning

Figure 1: A document set up for guided notes in the form of fill in the blank pre-questioning

Graphic Organizers

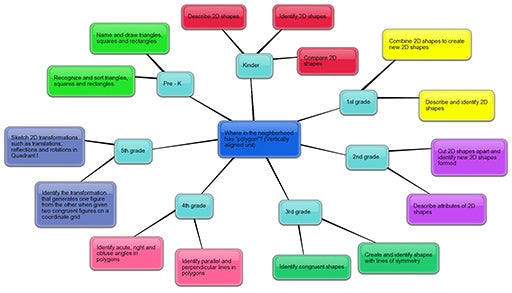

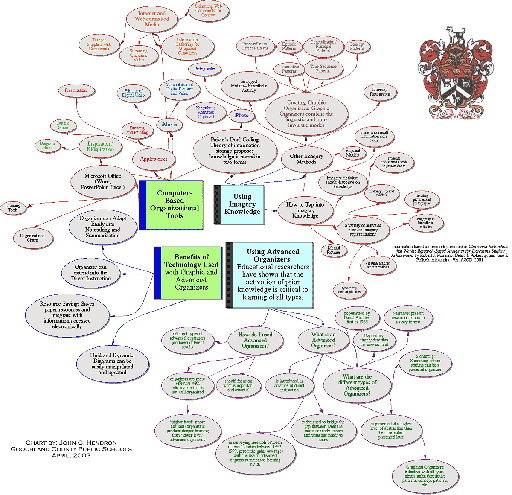

Graphic Organizers capitalize on both linguistic and non-linguistic styles of information storage. There are many different kinds of graphic organizers. Some include concept maps (figure 2), Venn diagrams, or; cluster maps (figure 5). (Coffey, 2006) Thinking maps (figure 6) which can also be included in this category, are often used in the public schools, and thus may be familiar to students in the college classroom as a way of seeing connections between or progressions of ideas. In comparison, concept maps have shown potential for facilitating knowledge retention and transfer as compared with reading text passages, listening to lectures, and participating in class discussions (Nesbit, 2006), by simply helping to bridge the gap between different types of student learners and their learning preferences.

Graphic Organizers are not just for lecture settings. They can also be used when writing papers or creating a project – organizing processes such as brainstorming, sequencing, comparing and contrasting, and analyzing. These organizers have been proven helpful to students who learn best with visually presented information. (Amin, 2005) Graphic Organizers can also be very helpful in the facilitation of collaborative learning environments. (Larson, 2009) For more information about Graphic Organizers, watch the video below.

Figure 2 Concept Map Example (click for pdf)

The video below highlights different types of Graphic Organizers and their many purposes.

Figure 3: Cluster Map Example (click image above for pdf)

Figure 3: Cluster Map Example (click image above for pdf)

Figure 4: Thinking Map Examples (click image above for pdf)

Narrative

Narrative Advance Organizers use stories to activate background knowledge allowing students to make connections to things they already know. This type of organizer uses a personal connection to inspire learning. For example, if an instructor is introducing a new unit on Germany, it may help if he/she shares a detailed story about the location where students can relate and potentially make connections. This creates student engagement and can be a powerful tool when used at the beginning of a unit. The difference between a story told for enjoyment and one used as an advance organizer is that the instructor will intentionally connect elements of the story and the content of the lesson early on and throughout the class period.

The video below is from McRel – Classroom Instruction that Works (2nd Edition). It highlights the effectiveness of three different types of Advance Organizers.

Student Engagement and Use of Advance Organizers

The use of Advance Organizers is helpful for a wide variety of students, but this organizational strategy is especially effective for students with learning differences or for students who are visual learners. Students find that Advance Organizers provide a framework for preparing for class, a useful tool during note-taking, and an excellent resource for studying during exam preparation.

Students have shared that they benefit from different kinds of Advance Organizers for a few key reasons. First, students want to know what the instructor considers important. This is not necessarily just in order to know what to study for course tests, but knowing the critical core information in the class establishes the key ideas for students. From there they can use those key ideas on which to “hang” supporting details, examples, applications, etc. A stronger understanding of these types of connections between ideas will likely increase student understanding of course material in general. Students also want to know how to structure their notes, and can use instructor-provided frameworks for doing so. The clearest outline in the mind of an instructor does not always automatically come through to students in the class – thus missing an opportunity for students to make important connections. Third, students want to be able to overcome the challenge of listening, understanding, and writing notes all at the same time. Finally, students want to have clarity about the course which includes the feeling that they didn’t miss anything during the lecture and in their notes. (Van der Meer, 2012) The use of Advance Organizers, when presented properly by an instructor, does not necessarily discourage students from taking notes. On the contrary, students are able to leave class with a much more comprehensive set of notes (that include not only core ideas but also examples, anecdotes, and notes from questions/class discussions).

Research suggests student use of Advance Organizers helps with listening; comprehension; connecting information with prior knowledge; and building confidence motivation and attentiveness. (Jafari, 2012) Students who are using Advance Organizers have commented during the course evaluation process and through faculty instruction nomination forms, that they like the ability to “stay connected” and the “feeling of involvement that the organizer provides”. Students favor having notes available prior to class which helps reduce their stress level during class. Instead of worrying about trying to write everything down, students are able to ask questions and pay attention to examples to gain a better understanding of important course content.

Students add that course content provided through Advance Organizers may seem more clearly structured. Research completed in Germany using 48 first year Psychology students found that a well-structured Advance Organizer provides a better learning outcome than less-structured organizers. (Gurlitt, 2012) Additionally, students prefer Advance Organizers that have headings and subheadings so that information provided can be put into categories and easily located. (Larson, 2009) Students have found web notes, which instructors provide via email or through an online instruction website like “Blackboard”, are increasingly effective when attending lectures. Students like the ability to add their own notes (in addition to what the instructor provided) and feel this approach helps their attention and motivation during class. (Sambrook, 2010)

Advance Organizers encourage student engagement which aligns with the UDL Principle “Multiple Means of Engagement”. Students are stimulated by information that is relevant to their success in their college courses. When professors provide Advance Organizers as a supplement to their course, they provide students with materials essential for learning prior to direct instruction. Therefore, students can begin to actively engage in the learning process before they even step foot in the classroom. This empowers students to take ownership over their learning thus creating motivation and self-advocacy.

Technology and Note-taking Advantages when using Advance Organizers

Advance Organizers are examples of high quality instructional tools which help build confidence, make knowledge meaningful and memorable, and help students make connections. (Dean, 2012) Organizers can take on many different forms and can be created using different technology tools.

Instructors and students are both benefiting when it comes to what technology provides in regard to Advance Organizers including; the variety of creation option, ease of manipulation, and ability to provide instant updates. For example, electronic diagrams can be created as a teacher template and later completed by the student to use as notes for studying. Also, the implementation of technology through the creation of Advance Organizers helps to cut down on the depletion of resources such as paper and copier use. (Hendron, 2003)

Another benefit of using Advance Organizers is that they are extremely versatile across different disciplines. Mentioned in this module alone, Advance Organizers are being used in the disciplines of Psychology, Trends in Education, and Business courses. For more examples of additional subject specific Advance Organizers, including Science, English and History, please visit John Hendron’s website.

Note Taking

Advance Organizers provide a means of filling the void students often face when taking notes by encouraging active listening. Handouts given with incomplete details are more effective on student’s performance than students taking their own notes. (Larson, 2009) Students are often stressed and concerned during note taking with the perceived need to write everything a professor says.

Students can become so focused on the note-taking itself that they miss key examples and scenarios that drive home crucial points needed for understanding. In fact, evidence shows that student’s notes include less than 50% of what is presented by the instructor during a lecture. (Sambrook, 2010) Advance Organizers can help fill the void by providing students with key terms, definitions, images, and key concepts which are critical to success in the course. Thus, Advance Organizers can help students during pre-class preparation, in class note taking, and post class studying of important exam material.

Memory is another concern associated with note taking post lecture. Students are encouraged to review their notes after class and when studying, but a big concern is how much the students are actually remembering just from taking notes. Students are far more able to remember key concepts if active engagement takes place in the form of hands on activities and if examples are provided during instruction. Sometimes students are so busy taking notes, these other forms of engagement are swept aside. Research shows that note taking has an influence on memory if there is an increase in engagement and activities relevant to concepts presented in class. (Bohay 2011) suggests that verbatim memory is increased when students take notes in combination with participating in application activities. This research also found that participants who were able to review their notes post lecture, had even better performance on testing and other assignments necessary to success in the course. This can be related to a deeper understanding of important concepts.

Students agree that note taking is essential when studying for exams. However, exam preparation productivity increases greatly with high-quality notes. When students are presented with visual representation of knowledge during note taking many believe it helps in understanding major ideas of the course. (Coffey, 2006)

Summary

There are multiple types of and uses for Advance Organizers in the instructional setting. Learning outcomes have been widely positive and highly supported with use of the types of organizers listed below. Advance Organizers encourage student engagement, which aligns with the Universal Design for Learning principle Multiple Means of Engagement. The following types of Advance Organizers have been presented here

Expository

- Depicts new content (clear cut and factual)

- Informs students specifically about the material they are going to learn or explains the general ideas in advance

- Reviews in advance definitions that students will come across during the lesson

Comparative

- Activates existing knowledge to facilitate the later integration of new ideas

Text

- Assists students with note-taking, the writing process, and brainstorming and/or organizing ideas

- Offers flexibility in development options such as outlines, guided notes, PowerPoint slides, verbal directions, and pre-questioning techniques.

Narrative

- Use of a story to prepare students for instruction

Graphic

- Visually represents how new information will fit together and is organized

- Offers a wide variety of formats such as Concept Maps and Venn Diagrams.

- Offers versatility for purposes such as organizing lectures, brainstorming, structuring the writing process

Instructors are also finding Advance Organizers are easy to develop and use within a wide variety of instructional settings. Advance Organizers are most effective when used at the start of a unit, discussion, question-answer period, homework assignment, video, student textbook reading, or hands-on activity. (Allen, 2014)

Advance Organizers are especially effective when created using principles such as consistence, coherency, and creativity. This organizational strategy is beneficial for all learners in the classroom, but critical for students with learning differences or those who are visual learners. Research suggests student use of Advance Organizers aid in listening, comprehension, connecting information with prior knowledge, building confidence, motivation, and attentiveness. (Jafari, 2012)

Advance Organizers enhance students’ motivation to learn (Shihusa, 2009) by providing students with key terms, definitions, images, and key concepts which are critical to success in the course. These organizers are useful during pre-class note preparation, in class note taking, and post class studying of important exam material. Advance Organizers are also complimented by students and instructors due to their ease of use, creation, and manipulation as well as their versatility of use across multiple curriculums.

Learn More

Literature Base

Advance Organizers are high quality instructional tools which help build confidence, make knowledge meaningful and memorable, and help students make connections. (Dean, 2012) According to David P. Ausubel, Advance Organizers are easy to develop and practice within a wide variety of educational settings. Additionally, an instructor with accurate educational training can create and use Advance Organizers making them a vital instructional tool in a student’s capacity to retain new information. (Allen, 2014)

Advance Organizers are to be used as educational tools to aid in a learner’s education, not to replace valid instructional materials. (Allen, 2014) Due to classroom dynamics and the increase of student learning differences, instructors and educators are implementing and applying their own styles and approaches to using Advance Organizers.

Not only are Advance Organizers increasing student engagement, but they are also being studied in direct correlation to their effect on helping students with recall and memory. Twenty four experiments have yielded positive student results when Advance Organizers are given prior to instruction, when students have enough time to study the organizer prior to being presented new information, and when they are tested for recall after a short delay. (Corkill, 1992) When instructors use visual aids such as PowerPoints, video clips, and hands-on activities students are better able to take notes and understand important concepts. Additionally, studies show that struggling students benefit when instructors teach them organizational skills, study skills, and how to effectively use Advance Organizers. (Maydosz, 2010)

When students are presented with visual representation of knowledge during note taking most believe it helps in understanding major ideas of the course. (Coffey, 2006) Handouts given with incomplete details are more effective on student’s performance than students taking their own notes. (Larson, 2009) Results show that there is a boost in verbatim memory when notes are taken as well as in performance. Additionally participants who were able to review their notes had even better performance on testing and other assignments necessary to success in the course. This in turn causes deeper understanding of important concepts. (Bohay, 2011)

Student learners need instruction to be clear, easy to understand, and relevant to one’s growing network of knowledge. Students in a Computer Science course agreed that use of visual representations such as concept maps (graphic organizers) were helpful in studying for exams, and in helping to understand major course concepts. (Coffey, 2006)

References & Resources

Allen, A., Exsted, T., Miley, T., Pulkkinen, T. (2014) Ausubel and Advance Organizers. Retrieved fromhttp://im404504.wikidot.com/template:new-template-ltpages

Amin, A.M. (2005). Using graphic organisers to promote active e-learning., 4010-4015. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/20702/ Retrieved from EdITLib

Bohay, M., Blakely, D. P., Tamplin, A.K., & Radvansky, G.A. (2011). Note taking, review, memory, and comprehension. The American Journal of Psychology, 124(1), 63-73. doi: 10.5406/amerjpsyc.124.1.0063 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21506451 Retrieved from JSTOR

CAST (n.d.) About CAST: What is Universal Design for Learning. Retrieved fromhttp://www.cast.org

CAST (2009). CAST UDL Online Modules.

CAST (2011a). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines Version 2.0. Retrieved from http://www.cast.org

Coffey, J. (2006). Getting the big picture: Visual advance organizers in computer science course presentation. 1785-1791. http://www.editlib.org/p/23248 Retrieved from EdITLib

Corkill, A.J. (1992). Advance organizers: Facilitators of recall. Educational Psychology Review, 4(1), 33, doi: 10.1007/BF01322394. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2FBF01322394http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01322394 Retrieved from Springer Link

Dean, C. B., Hubbell, E. R., Pitler, H., & Stone, B. (2012). Cues, Questions, and Advance Organizers.Classroom Instruction that Works Research-Based Strategies for Increasing Student Achievement. Denver: McRel.

EnACT. (n.d.) 14 common elements of UDL in the college classroom.

Evans, C., Williams, J. B., King, L., & Metcalf, D. (2010). Modeling, guided instruction, and application of UDL in a rural special education teacher preparation program. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 29(4), 41-48. Retrieved from Education Research Complete.

Fohlmeister, R. (2010). Concept Map. Retrieved fromhttp://mathmastermindgeometry.pbworks.com/w/page/22808165/Concept%20Map

Gurlitt, J., Dummel, S., Schuster, S., & Nuckles, M. (2012). Differently structured advance organizers lead to different initial schemata and learning outcomes. Instructional Science: An International Journal of the Learning Sciences, 40(2), 351-369. doi: 10.1007/s11251-011-9180-7. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ956168&site=ehost-live

http://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs11251-011-9180-7″ target=”blank Retrieved from EBSCO HOST and Springer Link

Helterbrand, Sherri. (2012). Cues, Questions, and Advance Organizers. Region 14 State Support Team. Prepared for Bright Local Schools Summer Academy.

Hendron, J. (2003). Advance & Graphical Organizers: Proven Strategies Enhanced through Technology. Goochland County Public Schools.

Heward, W. (n.d.) Guided Notes – Improving the Effectiveness of Your Lectures. The Ohio State University Partnership Grant: Fast Facts for Faculty.

Immordino-Yang, M., & Damasio, A. (2007). We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education. Mind, Brain & Education, 1(1), 3-10. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-228X.2007.00004.x https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1751-228X.2007.00004.x Retrieved from Wiley Online Library

Jafari, K., & Hashim, F. (2012). The effects of using advance organizers on improving EFL learners’ listening comprehension: A mixed method study. System, 40(2), 270-281. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2012.04.009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2012.04.009 Retrieved from ScienceDirect

Konrad, M., Joseph, L., Itoi, M. (2010). Using guided notes to enhance instruction for all students. Intervention in School and Clinic, 46(3), 131. doi: 10.1177/1053451210378163http://isc.sagepub.com/content/46/3/131.full.pdf+html

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1053451210378163 Retrieved from SAGE Journals

Larson, R.B. (2009). Enhancing the recall of presented material. Computers & Education, 53(4), 1278-1284. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2009.06.010.http://jw3mh2cm6n.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=Refworks%3A&charset=utf-8&_char_set=utf8&genre=article&aulast=Larson&auinit=R.B.&title=Computers%20%26%20Education&stitle=Comput.Educ&date=2009&volume=53&pages=1278-1284&issue=4&atitle=Enhancing%20the%20recall%20of%20presented%20material&spage=1278&au=Larson%2CRonald%20B.%20&

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.06.010 Retrieved from ScienceDirect

Maydosz, A., & Raver, S.A. (2010). Note taking and university students with learning difficulties: What supports are needed? Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 3(3), 177-186. doi: 10.1037/a0020297

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0020297 Retrieved from EBSCO HOST

Mayer, R.E. (1979). Twenty years of research on advance organizers; Assimilation theory is still the best predictor of results. Instructional Science: An International Journal of Learning Sciences, 8(2), 133. doi: 10.1007/BF00117008.

McGuire, Ken. (2012). Leadership and a Common Vision.

National Center on Universal Design for Learning. (2011). About UDL. Retrieved fromhttp://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl

Nesbit,J.,Adesope, O. (2006). Learning with concept and knowledge maps: A meta-analysis Review of Educational Research, 76(3), 413. doi: 10.3102/00346543076003413http://rer.sagepub.com/content/76/3/413.full.pdf+html

http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00346543076003413 Retrieved from SAGE Journals

Rose, D., & Dalton, B. (2009). Learning to read in the digital age. Mind, Brain & Education, 3(2), 74-83. doi:10.1111/j.1751-228X.2009.01057.x http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-228X.2009.01057.x

Rose, D. H., Harbour, W. S., Johnston, C. S., Daley, S. G., & Abarbanell, L. (2006). Universal design for learning in postsecondary education: Reflections on principles and their application. Journal of Postsecondary Education & Disability, 19(2), 135-151. Retrieved from Education Research Complete.

Rose, D. H. & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum. Retrieved from http://www.cast.org

Sambrook, S., & Rowley, J. (2010). What’s the use of webnotes? Student and staff perceptions. Journal of further and Higher Education, 34(1), 119-134. doi: 10.1080/03098770903480338

Shihusa, H., & Keraro, F.N. (2009). Using advance organizers to enhance students’ motivation in learning biology. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science & Technology Education, 5(4), 413-420. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=51502325&site=ehost-live

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/150d/fb7a8075c98dfb31f4323f7cbf2d7b46581f.pdf Retrieved from EBSCO HOST

UDLCAST. (2011, October 7). Introduction to UDL [Video file]. Retrieved fromhttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MbGkL06EU90&feature=relmfu

Van der Meer, J. (2012). Students’ note-taking challenges in the twenty-first century: Considerations for teachers and academic staff developers. Teaching in Higher Education. 17(1), 13-23. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2011.590974. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2011.590974

About the Author

Morgan James

STEPP Program

East Carolina University

Derrick Wirtz

Psychology

East Carolina University

Tiffany Woodward

Business Management

East Carolina University