Alternative Assessments: Assessing LEARNING, Not METHOD

Contents

Introduction

In academia we tend to have specific traditions related to how we assess students: writing assignments, lab reports, oral presentations, tests, etc. However, these assessment methods often require students to master the method of delivery even before getting to the content itself. For a term paper in a history class, for example, a student earns their grade in part based on their ability to write a well-formed paper – regardless of whether writing was an intended learning objective for the course.

The trouble with this approach is that students come to our courses from a variety of backgrounds and for a variety of purposes. While we can expect them to have a basic level of proficiency with the written word, for example, it is less likely that they will have mastered communication in the forms generally expected in a specific discipline. As a result, an instructor often needs to choose between spending time teaching students to write in the accepted format for their discipline, providing resources and expecting students to figure it out for themselves, or simply providing assignments and hoping for the best.

And the results are often less than pleasing. Students struggle to identify proper formats and approaches, graders get frustrated as they wade through an array of sub-par written work, and everyone wonders if the grades students are assigned really match up with the degree to which they have mastered the skills the instructor really wanted them to master in the first place.

One source of this problem is that we typically start our assessment design with a predetermined mode of response in mind. We begin, for example, with the idea that there should be some specific number of homework assignments, periodic tests or quizzes, presentations, written work, and so on – all layered in a certain way through the semester. We take care to build things in a worthwhile progression through the semester, even offering low and high stakes assignments with plenty of feedback to help students through. But what we forget is that each assignment mode carries with it a skill set that students must also master, in order to perform well.

One way around this problem is to focus our assessment design around content and learning objectives, with permission given to students to vary their method of response. Suppose for example I have asked my students to write a short reflection paper in response to a reading assignment. As an alternative, I might ask them to respond either in writing or through some other method, chosen by them. I can grade their responses according to a rubric that aligns with the learning objectives and goals for the assignment, while giving students the freedom to present their work in a form that suits their interests and capabilities.

This is the alternative assessment model: giving students license to express what they have learned using methods chosen by them, rather than prescribed by their instructor. The result is a situation where barriers related to the format of assessment are removed, and student grades are more likely to reflect levels of student mastery. Instructors can continue to hold students to high standards for content mastery, and students can bring increased effort and creativity to their work.

Objectives

The purpose of this module is to present details of this alternative assessment model, equipping readers to implement their own version, in their own context. After reading this module, you should be able to:

- Identify appropriate contexts for leveraging an alternative assessment model;

- Implement the alternative assessment model in your course(s) by designing assessment tools that minimize barriers related to the format of an assessment; and

- Explain the value of the alternative assessment model by way of its contribution to student motivation and aligned assessment design.

UDL Alignment

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression

The alternative assessment model provides students with the opportunity to demonstrate their learning and mastery of content and concepts through multiple means. More importantly, students are permitted to choose their method of response and express their thoughts through means that are comfortable for them. In addition, by explicitly sharing learning goals with students (a key feature for this approach to assessment), they are provided with targets for their own goal-setting, planning, and strategic development. Taken together, this alternative assessment model benefits students by allowing every individual to draw on their own strengths in order to demonstrate their skills – thereby removing unnecessary barriers to assessment of learning.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Engagement

By lifting the restriction of response mode from an assignment, students are immediately faced with the opportunity to engage in their learning (and demonstration of their learning) through multiple means. This in turn allows students to follow their own interests and respond to assignment prompts in ways that maximize their own investment: students find relevance, value, and opportunities for authentic expression when they are permitted to select their own mode of response. This further increases student motivation, and tends to positively impact the quality of work they produce – all by simply allowing them to design their own response method!

Instructional Practice

The basics of the alternative assessment method are quite simple:

- Pick a class

- Pick a project/assignment

- Allow students to provide an alternative format/method for their presentation

In fact, you need not specifically change anything about a previously developed assessment prompt, except to eliminate specifics about the mode of response.

Steps for Successful Implementation: Best Practices

Providing students with alternatives may cause some consternation among your students: choice can be disconcerting at first, and so it is important to provide a structured approach to the implementation.

Step 1. Introduce the Concept

Present the idea of the alternative assessment to students early in the semester. Include a description on your syllabus, briefly (and enthusiastically) highlight the opportunity on the first day of class, and share examples of previous student work. For your first time through you might simply use suggestions from below, under what to expect, to give students a sense of the possibilities.

Step 2. Provide Smaller Choice Opportunities

Choice can be uncomfortable for students, and it can feel like a risk that might not be worth taking. In order to mitigate this effect for a final project, look for smaller ways to give students choice throughout the semester. For example, are there smaller assignments for which choice between different prompts might be appropriate? Or is there an assignment where you can give your students the opportunity to use one of three specified modes of response? Using lower stakes assignments to help students experiment with choice is a useful way to increase the effectiveness of the alternative assessment method for larger projects.

Step 3. Create the Assignment Prompt

When you create your assignment prompt using this alternative assessment model, there are two things in particular to make sure you do. First, include an explicit statement of the learning objectives or goals around which this assessment was built. For example, if the goal is for students to demonstrate their ability to apply a set of concepts to a real-world situation, then state that explicitly. If the goal is for students to present their perspective on a specific type of issue, then state that explicitly. By making this the starting point and the centerpiece of your assignment information for students, you turn their attention to what’s important (your learning goals and the keys to successful assessment completion), and away from the details that are less important for the sake of grade allocation (e.g., the specific format requirements for the assignment).

Second, it is useful to create parallel trajectories for students who choose to stick with a more traditional assessment mode (e.g., write a paper) and those who select an alternative delivery mode. For example, due dates and progress reports should come at similar times, workload expectations should be consistent between the options, and grading scales should be similar (see below for more discussion of the how-to’s of grading alternative assessments). This parallel trajectory and expectations help to eliminate potential perceptions of lack of equality or fairness between the two trajectories. In addition, keeping things similar in these ways eliminates additional barriers for students who might otherwise not engage with the assignment in a creative and dynamic way.

Step 4. Discuss the Assignment in Class

Much like Step 1, it is important to use some class time to present the alternative assessment options to students. This need not take a lot of time, but it is another opportunity for you to re-frame the assessment for students so that they think about it in terms of the goals and learning objectives of the assessment – instead of simply the dance they need to do to get their grade in the course. Focus on the purpose of the assignment, the opportunity you are giving them to engage with the assignment in a creative way, and the opportunity for them to use their existing skills to demonstrate their knowledge and mastery of course content. Finally, by sharing some ideas or examples of past work, you will help students begin to come up with their own ideas while also normalizing the alternative assessment choice.

Step 5. Request Proposals

For final projects and term papers, it is often useful to ask students to turn something in at an early stage, in order to help them make progress and in order to provide them with some feedback and direction. With the alternative assessment method, this step is vital. In particular, the first stage of the assignment should be for students to submit their proposal for their project. You’ll want to know what they plan to do, and how they plan to do it. Ask them to describe their ‘deliverable(s)’, along with a timeline for completion of their project. For those selecting a non-traditional mode, it is also useful to ask them at this stage if they would like to share their final project with the rest of the class (at an end-of-semester showcase, for example). If you also plan to provide an opportunity for students to turn in drafts of their work, ask them to indicate what they would like to turn in at the draft-submission point in the semester.

Once proposals are received, aim to provide quick feedback for students about the scope and design of their work, and information about how their project will be graded. This is also an opportunity to add specific requirements for students, to make sure you are getting what you need from them. For example, a student who decides to produce a painting as their deliverable may need to also provide you with a short written submission to explain the ways in which their artwork serves as a response to the given prompt. This less formal piece of writing allows you to understand what’s in the student’s mind without having to guess what’s intended by their artwork, and without requiring them to write according to the norms of your discipline.

One final piece to consider at the proposal stage is the extent to which you will allow students to change their minds. Some students may be nervous about selecting an alternative assessment mode, and allowing some flexibility for changing of minds can help allay those fears. In your feedback, set a deadline for this type of student to indicate the point-of-no-return – so that they have some time to experiment, but so that they also get started on the work with sufficient time remaining before the assignment deadline.

Step 6. Check-in & support

If you have the capacity to do so, it is useful to allow students to turn in partially completed work, or to meet with you outside of class to share their work and talk about any specific issues they may be facing. This is another way to help reduce student anxiety that arises due to the lack of specific formula or ‘rules’ for the assignment. Often a quick look at what they’re doing followed by an email affirming their choices to date (and/or some redirection through feedback) provides a student with the confidence they need to complete their project. They may be wondering how their assignment will be graded, so focusing comments on how their work can be developed to best meet the criteria for the assignment is a good approach to take. Overall, use your existing mechanisms for communication with students (e.g., email, office hours, chat platforms, etc.), and focus on providing students with information they need to successfully and confidently turn in completed work.

Step 7. Final Showcase

One of the best parts about the alternative assessment method is the creativity with which students approach their work. If at all possible, aim to use the final day of your class for students to display and share their work. If someone has designed a board game, allow them to explain it briefly to the class and then let students try it out. If someone has developed a complex metaphor or written a poem, allow them to read it to the class. Vary your format according to the sorts of projects students have developed, and use it to wrap up your class narrative in a way that leaves everyone feeling positive about the course.

Step 8. Grading

Alas, every assessment ultimately needs to be turned into a grade for our students. The question is, how can we possibly grade such a diverse set of projects without crying ourselves to sleep?!

As it turns out, the answer is quite simple: since you started with specific learning objectives and goals for the assignment, aim to grade each assignment in line with those specific learning objectives and goals! The point is not to get overly focused on the mode of delivery, but to focus on the content and demonstration of specific mastery of specific knowledge or skills. Further, a good place to start is to think about the criteria you might use to assess a deliverable in a traditional format. Describe those criteria, then revise your descriptions by removing specific mention of the mode.

For example, consider the following set of grading criteria for use in a Modern Philosophy course:

| Criteria | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Clarity & Use of Medium (25%) | Effective use of chosen medium for delivery of content. Easy to identify your message/key points from what you’ve provided. |

| Connection to Modern Era Themes & Authors (25%) | Project effectively and (to some degree) explicitly incorporates and interprets Modern Era themes and philosopher contributions. |

| Sophistication & Depth (40%) | Project provides a robust response to your chosen prompt, with attention paid to the nuances involved. Your response goes beyond a rehearsal of in-class discussion. |

| Creativity (10%) | Unique thoughts and/or artifacts, curated by you. |

With a loose rubric like this, you can see clearly which criteria are important, and it should also be easy to see how you might use this to grade a students’ piece of artwork, a speech given to the class, a policy proposal, a social media experiment, a traditional philosophy paper, and so on. Ideally, you will have had smaller assignments throughout the semester that have relied on similar criteria, and so students will already be comfortable with the general ideas behind them. As a result, both they and you should be able to fairly easily translate your criteria to different assignment modes. Remember: while some points may be given for the use of the medium (as in the sample above), the point is to focus on the principles beneath a successful project.

What To Expect

Once you manage to unleash your students’ creativity, you will undoubtedly be surprised and impressed by much of what they create. More than anything, you can expect many of your students to dedicate more time and attention to their project than they would have if they had not been given the sort of choices this approach allows. However, it is also useful to have some idea of what you can expect. Based on my own experience and comparison with a few others who have implemented their own versions of this alternative assessments model, here’s what you can expect to receive from students:

Figure 1: Original Artwork — paintings, sketches, photo essays, etc.

Figure 2: Creative Writing — children’s books, short stories, poems, etc.

Figure 3: Games — board games, card games, role-playing games, etc.

Figure 4: Metaphors: something from their life and experience, with robust connections made to the concepts in your class.

Figure 5: Artistic Performances: original songs, interpretive dance, etc.

Figure 6: Artistic Performances: original songs, interpretive dance, etc.

Figure 7: Multi-media Presentations: video blogs, websites, audio essays, speeches, etc.

Figure 8: Popular Media Use: buzzfeed quiz, memes based on course content, etc.

Learn More

The alternative assessment method described in this module is well-grounded in the research on teaching and learning. In what follows you will see three specific ways in which this alternative assessment method aligns with well-established, evidence-based best practices in teaching and learning.

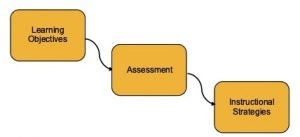

Backward Design & Alignment

One of the foundations of effective course design is the backward design method (Wiggins & McTighe, 1998). The general idea is that our first step in effective course design is to identify the goals – or learning objectives – for our students. What is it that we want them to be able to do by the end of the course? With this in hand, we can then construct assessment tools that will help us determine whether students have in fact gained the ability to do what it is we want them to be able to do by the end of the course. From there we can also build in our approach to teaching the class, using methods and approaches to content that are likely to teach students the things we want to teach them, so that they can in fact perform well when assessed, thus demonstrating their levels of mastery with respect to our learning objectives for the course. And this of course is a connection to Universal Design for Learning at a most basic level: if we begin with learning objectives in mind, and let that direct our course design, we can easily remove many of the barriers to effective assessment – as discussed throughout this module – by focusing on assessing learning rather than assessing a particular method or mode of performance.

Figure 9: Backward Design as presented by Wiggins & McTighe (1998)

To further our efforts in effective course design and assessment, Dee Fink (2003) reminds us that the key components must be integrated, or sufficiently aligned, in order to operate well together. That is, our courses are most likely to result in high levels of student learning when our learning objectives, assessment methods, and instructional strategies are all sufficiently in sync with one another. Backward design is a process that tends to lead to this sort of alignment, which then leads us to rich and rewarding learning experiences.

Further, Fink (2003) draws on Campbell & Smith (1997) to provide us with a strong case for the integration and use of learning objectives in our course design and in our development of learning objectives. While the “old paradigm” of teaching leads us to assess students in line with specific norms, drawing on traditional methods like multiple-choice tests and term papers, the “new paradigm” – the paradigm where significant learning occurs – is based on well-established criteria, and allows for assessment of performance in a variety of ways. This, again, is where the connection to the principles of Universal Design for Learning is situated.

The use and communication of learning objectives is known to support student learning in multiple ways (see Anonymous (n.d.) for a good summary). Further, a crucial part of the process of assigning meaningful grades to students is the presentation of clear expectations for each task, along with information about the criteria that will be used to assess performance (Collier & Morgan, 2008). As a result, the role of learning objectives in the development of any assessment tool is important, and there is value in communicating those objectives to our students along the way.

In other words, the reliance on learning objectives in the alternative assessment method described in this module is well-grounded in evidence-based best practices for course design. Taking an approach to assessment that focuses on criteria, goals, and objectives allows us to escape the problems created by reliance on specific modes of assessment, while also strengthening the connection of our assessment tools to their purpose in the context of our courses. And by escaping from these problems we also open ourselves up to accepting work from students from an array of learning profiles, thus creating mechanisms for authentic assessment of their work.

Learner-Centered Teaching & Student Autonomy

One of the markers of contemporary teaching and learning in higher education (in the West) is the drive to give students an active role in the process. Gone are the days when the instructor takes the role of sage on the stage while students dutifully record the instructor’s words for future reference and study. Instead, the goal is to put the learner at the center of the endeavor and to equip the instructor to design learning experiences that take their students’ needs, interests, and opinions into account.

As championed by Mary Ellen Weimer, this is the learner-centered teaching model. The balance of power is shifted from instructor alone to instructor + students. Our focus shifts from the content we want to teach, to the things we want our students to be able to do with the knowledge they have gained. The instructor becomes the facilitator of learning, focusing on developing learning opportunities and activities for students. The teacher aims to motivate the student, and the student makes decisions about the extent to which they will engage in the learning process. (Weimer, 2013).

With this as our framework, providing students with choice seems almost mandatory. The alternative assessment method described in this module is an opportunity for students to be active partners in their learning. Through this active participation, students are then empowered to express themselves in ways that fit with their own strengths, helping to remove the challenges that can arise when the principles of Universal Design for Learning are neglected.

Motivation, Learning, and Performance

It is well-established that motivation is an integral part of both learning and performance/accomplishment – in the workplace, in sports performance, and in education (e.g., Ambrose et al, 2010; Colquitt et al, 2000; Deci & Ryan, 1985; De Raad & Schouwenburgh, 1996; Kanfer, 1991; Locke & Latham, 2002). Motivation takes individuals to a place of directed action, which typically results in an increased level of performance and/or learning gains. Skills are acquired and put to use, tasks and projects are accomplished, and those supervising the work or learning are rewarded for the improved output.

Ambrose et al (2010) characterizes motivation as a key starting point for learning and performance. In their model of how learning works, they place motivation as a driver for goal-directed behavior, which in turn leads to learning and performance gains (see Locke & Latham (2002) for a complementary account). What is key for our purposes is the question of what factors contribute to motivation in the first place. Drawing on others before them, Ambrose et al (2010) pull out three core contributing factors: (a) the importance – or value – of a goal to the individual, (b) the individual’s belief – or expectancy – that they can in fact achieve the goal before them, and (c) the individual’s belief – or expectancy – that upon achievement of a goal they will be rewarded appropriately.

Further, the role of value in motivation can be better understood in terms of the distinction that is often made between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Simply put, we say that a person is intrinsically motivated when the source of their motivation comes from the accomplishment of the task or goal itself. For example, an intrinsically motivated student may work on solving a difficult problem just for the satisfaction that comes with success, or the inherent interest they have in the problem at hand. An extrinsically motivated individual, on the other hand, may be motivated to solve the same problem, but they do so for a reward or outcome that is external to the task itself – such as a grade or recognition from others.

Figure 11: Motivation and Learning as presented by Ambrose et al (2010)

Extrinsic motivation can be further broken down into different types, distinguished by the location of their source as external or internal to the individual. Ryan & Deci (2000) break it down into four distinct categories, as depicted in Table 2:

| Type of Extrinsic Motivation | Source of Motivation |

|---|---|

| External Regulation | External rewards/punishments |

| Introjected Regulation | Approval from self/others (ego-controlled) |

| Identification | Conscious valuing of activity, or self-endorsement of goals |

| Integrated Regulation | Incorporation into an internal hierarchy of goals |

In general, we expect student motivation to increase as the source of that motivation is more internal to the individual. So, for example, we can expect a student completing an assignment where they have been given no opportunity to connect with their own interests to show signs of weaker (or less persistent) motivation than a student who has been given the opportunity to engage with creativity and flexibility. The first student may feel annoyed at the arbitrary nature of the tasks forced upon them, while the second is likely to engage in a rich learning experience with a view to building a specific skill set they expect to be valuable in the future.

Building on this, research also shows that when we give students the power of choice, their motivation (and thereby their learning) increases. Locus of control – or the extent to which a person believes their fate is under their control – is a factor that has been shown to be related to academic and workplace achievement (Findley & Cooper, 1983; Kalechstein & Nowicki, 1997; Rotter, 1966; Spector, 1982). Furthermore, when a student believes they are autonomous – which tends to be the case when they are afforded the right to make decisions for themselves – their motivation and learning increases. (Deci & Ryan, 1987; Iyengar & Lepper, 1999; Skinner & Belmont, 1993; Zuckerman et al, 1978)

The alternative assessment method, then, connects up with the literature on student motivation in the following ways:

- Students who intentionally choose the mode of their response to the assignment prompt experience heightened levels of identification with their work, thus increasing their levels of extrinsic motivation.

- Students who engage in creative activity experience heightened levels of intrinsic motivation due to their investment in the work they are pursuing along the way.

- By giving students enough structure and support along the way, as well as a clear indication of the purpose and grading criteria associated with their work, student levels of expectancy (belief they will be appropriately rewarded + belief they can accomplish the goals) increase.

- Since students are making choices for themselves, they are able to target a level of challenge for themselves that is likely to be challenging enough to keep them interested, while not so difficult they do not feel they can achieve the goal. Again, expectancy increases.

Furthermore, we can see from this list that the alternative assessment model provides students with a framework that allows them to draw on their own strengths, while avoiding the often de-motivating factors associated with prescriptive modes for assessment. Since the goal is not to assess the mode of these assignments but instead the skills and knowledge embedded within, the alternative assessment model frees students to focus their energy productively, with a side of motivation and engagement along the way.

References & Resources

Ambrose, Susan A., Michael W. Bridges, Michele DiPietro, Marsha Lovett, and Marie K. Norman (2010). How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Anonymous (n.d.). The Educational value of Course-level Learning Objectives/Outcomes. Eberly Center for Teaching Excellence, Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved from http://www.cmu.edu/teaching, March 2017.

Campbell, W.E., & Smith, K.A., eds. (1997). New Paradigms for College Teaching. Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company.

Collier, P. J., & Morgan, D. L. (2008). “Is that paper really due today?”: differences in first-generation and traditional college students’ understandings of faculty expectations. Higher Education, 55(4), 425-446.

Colquitt, J. A., & Simmering, M. J. (1998). Conscientiousness, goal orientation, and motivation to learn during the learning process: A longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Psychology. 83: 654-665.

Deci, Edward L. & Ryan, Richard M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

Deci, Edward L., & Ryan, Richard M. (1987). The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(6), 1024–1037.

De Raad, Boele and Schouwenburg, Henri C. (1996). Personality in learning and education: a review. European Journal of Personality. 10(5): 303-336.

Dirks, Clarissa, Wenderoth, Mary Pat, and Withers, Michelle (2014). Assessment in the College Science Classroom. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman and Company.

Findley, Maureen J. and Cooper, Harris M. (1983). Locus of Control and Academic Achievement: A Literature Review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 44(2): 419-427.

Fink, Dee (2003). Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (1999). Rethinking the value of choice: A cultural perspective on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(3), 349–366.

Kalechstein, A. D., & Nowicki, S., Jr. (1997). A meta-analytic examination of the relationship between control expectancies and academic achievement: An 11-year follow-up to Findley and Cooper. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 123: 27-56.

Kanfer, R. (1991). Motivation theory and industrial and organizational psychology. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, edited by M.D. Dunnette and L.M. Hough, pp. 75-170. Palo Alto, CA: Consult. Psychol.

Locke, Edwin A. & Latham, Gary P. (2002). Building a Practically Useful Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation: A 35 Year Odyssey. American Psychologist. September 2002: 705-717.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied. 80: 1-28.

Ryan, Richard M. and Deci, Edward L. (2000). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology. 25: 54-67.

Skinner, E. A., & Belmont, M. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(4), 571–581.

Spector, P.E. (1982). Behavior in organizations as a function of employee’s locus of control. Psychological Bulletin. 91: 482-497.

Weimer, Mary Ellen (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: 5 Key Changes to Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Wiggins, Grant and McTighe, Jay (1998). Understanding by Design. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Zuckerman, M., Porac, J., Lathin, D., Smith, R., & Deci, E. L. (1978). On the importance of self-determination for intrinsically motivated behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 4(3), 443–446.

About the Author

Ruth Poproski

Ruth Poproski is the Associate Director for Teaching and Learning at the Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) at the University of Georgia (UGA). She leads the CTL’s team focused on educational development for all instructors, TAs and future faculty across campus, learning technologies, TA development and recognition, and the scholarship of teaching and learning. Prior to joining UGA in 2019 Ruth worked at Carnegie Mellon University and then the Georgia Institute of Technology – as a Teaching Consultant and Assistant Director for Faculty Teaching and Learning Initiatives. She holds a Ph.D. and M.S. in Logic, Computation, and Methodology, and an M.A. in Philosophy. She has taught courses in Philosophy, Logic, and Game Theory, and is passionate about supporting good course design, teaching, and mentoring practices in higher education.