Contents

Introduction

Most students are required to read the same material, write the same tests, and complete the same assignments as all the other students. This traditional pedagogical strategy inherently disadvantages many students, which, in turn, also disengages many students. More than a century ago, Dewey (1916) argued such pedagogical strategies expect students to conform to the educational system, they afford students little freedom, and they ignore learners’ strengths, interests, and skills. An alternative approach provides students with options for reading materials and assessment tools that meet their individual needs and allow them to focus on their personal strengths, interests, and skills. This alternative pedagogical strategy is called “differentiated instruction” and is defined as the process of

“ensuring that what a student learns, how he/she learns it, and how the student demonstrates what he/she has learned is a match for that student’s readiness level, interests, and preferred mode of learning” (Tomlinson, 2004, p. 188).

A more nuanced definition is provided by Carol Tomlinson in the video provided in Figure 1. The relevance of this issue is illustrated by Biancarosa and Snow (2004, p. 8), who suggest that “as many as 70 percent of… [adolescents may] require differentiated instruction … targeted to their individual strengths and weaknesses”.

Based on seminal work by Tomlinson (1999, 2003), “differentiated instruction” has become widely adopted in practice. Over the past two decades, a substantial body of knowledge has been generated about the theory and practice of differentiating what or how a student learns. On the other hand, the theory and practice of differentiating how students demonstrate what they have learned has received considerably less attention. This scarcity of information on the theory and practice of “differentiated assessment” is surprising given Tomlinson’s (2004, p. 188) definition explicitly includes “how the student demonstrates” their knowledge. Therefore, this case study distinguishes between differentiated assessment and differentiated instruction as distinct, but related processes. Thus, differentiated assessment is defined as

the process of ensuring how a student demonstrates knowledge, ideas, and concepts matches their readiness level, their personal interests, and their preferred mode of action and expression.

Most pedagogical strategies allow the teacher to decide what, when, how, and where learning is to be assessed, including differentiated instruction and differentiated assessment. An alternative strategy would be to allow students to decide what, when, how, and where learning is to be assessed. Such a strategy would encourage students to have a “voice” in their learning (see Dewey, 1916) and “play an active role in the assessment process” (Francis, 2008, p. 547). This strategy may become increasingly necessary, as Francis (2008, p. 547) warns, because

… “the lecturer is increasingly seen as being fallible, and students are judged to be far more likely now than at any time previously to challenge methods of assessment and to expect greater input into the assessment process on their part.”

This looming challenge for the academy was recognized almost half a century ago by Friere (2005, p. 73), who warned that the education system emboldens students to conform with teacher demands and become passive participants in their learning.

Assessment empowerment allows students to become active participants in the assessment process. Assessment empowerment allows students to: (i) take control of the assessment of their learning; (ii) choose how they want to demonstrate knowledge, ideas, and concepts; and, (iii) allow them to actively focus on their personal strengths, interests, and skills. My accidental journey into the theory and practice of assessment empowerment began with ad hoc accommodations of students’ needs (e.g. new due dates, alternative test formats). Over my teaching career, I have also regularly allowed students to choose research topics of interest to them, provided choices on tests (e.g. answer three of five questions), and allowed students to choose due dates for tests and assignments. However, these choices may be better described as an expression of “critical democracy” rather than assessment empowerment.

My journey took an interesting turn in the fall of 2015. Students were permitted to choose any medium and means to communicate the results from their major research project (e.g. PowerPoint, poster, photo-essay, diorama, or interpretive dance). One particularly creative student used spoken word to poetically and passionately communicate a compelling, articulate, and well-informed story about the quality of drinking water on Indigenous reservations. This experience provided compelling evidence of the benefits from students playing an active role in the assessment of their learning. Since then, I have been expanding the choices in all my college classes, and especially for introductory (100 and 200-level) courses.

Objectives

The primary objective of this case study is to describe what assessment empowerment looks like in a college classroom. This case study also summarizes teacher’s and students’ experiences with assessment empowerment to provide an insider’s perspective. Collectively, this information describes how to implement assessment empowerment, it illustrates some of the benefits and challenges, and, it echoes the voices of the author and students who have experienced this means and medium of action and expression. After reading this case study, readers should be able to …

- Describe how multiple means of action and expression in a post-secondary course can be accomplished through assessment empowerment.

- Define assessment empowerment and describe its potential benefits to students and professors.

- Identify possibilities for applying assessment empowerment in their classroom.

- Plan to incorporate assessment empowerment into their classroom.

UDL Alignment

There is no single means or medium of action and expression that would be optimal for all learners. For example, some learners are adept at, and enjoy, expressing knowledge, ideas, and concepts through written communication, and others excel at storytelling, while others shine at the visual arts. It is also important to consider the mounting stress and anxiety among America’s adolescents and young adults, which is often amplified as they move away from their family for the first time to attend college. Stress and anxiety may also be associated with a specific means or medium of action and expression (e.g. exams or public speaking). This stress and anxiety would inevitably disadvantage, or even preclude, some students from expressing knowledge, ideas, and concepts. Therefore, it is essential to provide alternative modalities for action and expression that allows students to: (i) effectively navigate the learning environment; and, (ii) more appropriately (or more easily) express knowledge, ideas, and concepts.

Assessment empowerment, as the name implies, empowers students to play an active role in the assessment of their learning. This is accomplished by allowing students to choose how they want to demonstrate knowledge, ideas, and concepts in a way that actively focuses on their personal strengths, interests, and skills. Among the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) guidelines shown in Figure 2, assessment empowerment closely aligns with “Multiple Means of Action and Expression” by providing students with “options for expression and communication”. Assessment empowerment also aligns with “Multiple Means of Engagement” by providing students choices of assignments and content that most closely match their strengths, interests, and skills, which should also provide multiple “options for recruiting interests”. Moreover, by allowing students to literally earn the grade they want (by completing as many assignments as they want), assessment empowerment also provides course-long “options for sustaining effort and persistence”.

Instructional Practice

Students are individuals, which is also true for all of us; we all have our personal strengths, interests, and skills. Thus, for reasons of equity and fairness, it is important to provide students with alternative modalities for expressing knowledge, ideas, and concepts that focus on their strengths, interests, and skills. The consequences have important implications for student engagement and academic achievement. This case study describes how assessment empowerment was implemented in a 200-level World Regional Geography course. However, the principles and practice of this case study are generally applicable for a variety of grade levels, course content, and degrees of implementation.

A total of 46 students completed World Regional Geography course during the fall semester of 2016. Rather than the conventional approach of having a set of required activities (e.g. two tests and one term paper), students could choose from a variety of assignments that matched their personal strengths, interests, and skills. Moreover, students could continue to earn points, by completing as many different assignments as they wanted, until they earned the grade they wanted (see Resource #1 for an excerpt from the instructions in the syllabus). The first step was to design a wide variety of assessment items (see Table 1). When developing these assessment items, backward design principles were used to help maximize the relationships between the assignments and the course learning outcomes. Finally, it was important to consider how to provide options (or choices) for means and mediums of action and expression to ensure the assessment items matched the different strengths, interests, and skills of students in the course. The list of assessment items used in the fall of 2016 are illustrated along with individual and cumulative point values in Table 1.

| Assessment Item (n) | Points Toward Final Grade | Maximum Points |

|---|---|---|

| Participation | I will drop your lowest 5 scores (absences) | 10 |

| Chapter Quizzes (x 11) | 2 points each (+3 for completing at least 10) | 22 |

| Term Tests (x 4) | 10 points each (+3 for completing all 4) | 40 |

| Google Earth (x8) | 3 points each | 24 |

| Position Papers (x6) | 6 points each (+3 for completing at least 5) | 36 |

| Regional Profile (x1) | 30 points each (1 maximum) | 30 |

| Virtual Field Trip (x1) | 30 points each (1 maximum) | 30 |

| Why Geography Matters (x2) | 5 points (2 maximum) | 10 |

Students could choose any combination of assignments based on their personal strengths, interests, and skills. For example, if a student excels at writing tests and quizzes, they could choose to write several tests and quizzes (these options were incentivized with bonus points). If they are good at writing papers, and like to watch international films, they should attend movie night and write several position papers. The value of each assessment item in Table 1 was chosen to reflect the amount of effort required. It was important that these items balance the breadth and depth of problem solving, technical, creative thinking, critical thinking, written and verbal communication learning outcomes for the course. While, at the same time, providing choice of means and modes to express knowledge, ideas, and concepts. Therefore, the assessment items (Table 1) were designed, in part, to help ensure each item was able to simultaneously assess multiple learning outcomes. The occurrences of each item were chosen to help ensure that students would be required to complete more than one type of assignment to earn a passing, and certainly a higher, grade in the course.

Students were cautioned on the syllabus, and regularly throughout the semester, there was “only one way to mess this up, and that [was] to keep putting things off until the end of the semester”. Most assignments had weekly deadlines, and there were no “make-ups”, or extra-credit assignments at the end of the semester to earn more points. Students who attended class were regularly reminded (almost bi-weekly) that it was their responsibility to choose the assignments and plan their semester wisely. Due dates for assignments were posted in the learning management system (LMS) calendar, with e-mail notifications enabled. Despite the warnings, group and personal reminders, a few students were either unwilling or unable to take responsibility for playing an active role in the assessment of their learning. Consequently, based on formative and summative assessment, I designed “personal assignment schedules” (see Resource #1) to help those students who struggle with task initiation and task completion.

There is evidence to support the notion that assessment empowerment has the potential to enhance student engagement, which leads one to believe that providing regular opportunities to earn points throughout the semester would help “sustain effort and persistence”. However, it appears that this regular stream of opportunities was perceived or practiced differently by different learners. Many used this regular stream of opportunities to their advantage, but some to their detriment, especially those who were less motivated or less engaged in their learning. Despite the ability to earn as many points as you want (from a possible 202 points) to earn the grade that you want, and perhaps for a variety of reasons, a few students failed to earn a passing grade in the course (see Figure 3). Students’ comments reveal that many were unfamiliar with, and unprepared for, the responsibility of playing an active role in the assessment of their learning. While some students, for a variety of reasons, had no intentions on passing the course, some otherwise good students failed to capitalize on the regular stream of opportunities to earn points toward their final grade. Students’ comments from semi-structured interviews and course evaluations indicate that procrastination contributed significantly to their sub-optimal performance.

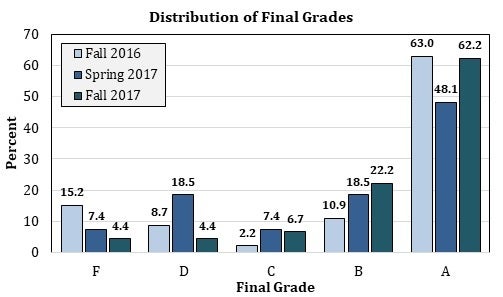

It is noteworthy that the 2016 application of assessment empowerment described in this case study allowed students to earn as many points as they wanted, until they achieve the grade that they wanted. This aspect of the assessment strategy has important implications. For example, if students were sufficiently motivated or engaged, there was a real possibility that every student in my class could have earned an A+. For that reason, I asked permission from my department head, in writing, to proceed with this “experimental” assessment strategy. Figure 3 illustrates the frequency distribution of final grades for three semesters of World Regional Geography. It is notable, however, that notwithstanding the absence of a traditional bell-shaped “normal” curve, not all students earned an A.

Figure 3: Histogram of Final Grades for three Semesters

It is true, however, that a disproportionately high proportion (48-63%) of students chose to work sufficiently hard (completing tests and assignments) to earn an A grade (≥90 points) in the course. Moreover, of the 29 students who earned an A grade in the fall of 2016, almost half of them (more than one-quarter of all students in the course) earned ≥100 points toward their final grade. A study by (Stan, 2012, p. 1999) found that 26% of students “learn for grades”, which may help explain the proportion of students who were sufficiently motivated to earn an A in this course. It may be interesting to explore the impacts of either playing an active role in assessment, or focusing on personal strengths, interests, and skills, or some other aspect of assessment empowerment has on motivating undergraduate students, recruiting their interests, and sustaining their effort for the duration of the course.

The Student’s Experience

Students’ perceptions about their experience with assessment empowerment were collected using a semi-structured interview from more than one-quarter of the students (n=12) near the end of the Fall 2016 semester (last two weeks of November). A sample of students’ comments have been categorized into either complimentary or constructive to represent the two dominant themes that emerged from the data.

| Complementary Comments | Constructive Comments |

|---|---|

| I liked being able to choose the assignments that fit my strengths and preferences. It made me feel like I had more control over my grade in the course. | It allowed me to push off my work a little too much due to my procrastination and not the choice of assignments. |

| We could choose the assignments best suited for us. I did not have to do any I did not want to. I was also able to do the assignments on my own schedule, which was nice. | There wasn’t really anything that I didn’t like about the choice of assignments. The only thing may be that I did more work the 2nd half of the semester instead of right away. |

| I could avoid types of assignments that I don’t like or that I’m not as good at. | It led to more procrastinating and not able to ask around to see what others are doing. |

The sentiments of students’ comments from the semi-structured interview (Table 2) are corroborated by comments on course evaluation forms. The breadth, depth, and variety of complimentary comments far outnumber the constructive, or critical, comments. It appears that students were especially appreciative of the ability to play an active role in the assessment of their learning. The other most frequently reported complimentary comment was the ability to meet the students’ individual needs, whether it was their personal strengths, interests, and skills, or the flexibility to work with their busy schedules. The constructive comments focus almost exclusively on students’ inability to overcome the tendency to procrastinate. These comments have led me to develop a “personal assignment schedule” (see Resource #2), which has helped reinforce the students’ responsibility that naturally comes with choice, autonomy, independence, and freedom. I also regularly check-in with students who may appear to be procrastinating for too long.

A Practitioner’s Insights

To be clear, assessment empowerment is more work for the professor. You need to design an array of alternative assignments for students to choose from, and then you must evaluate them. And, not only the assignments, the associated rubrics must be designed, developed, then loaded into the LMS. While most of the effort is front-loaded (i.e., before the course begins), there is the real possibility that more students will submit more assignments to earn more points, which means you will have to evaluate more assignments. Therefore, it is important that professors work with their LMS to automate some of the grading work (on-line quizzes and many of the Google Earth questions were graded automatically). Depending on class size, it may also be important to discuss the potential for teaching assistant support with your department head.

A high proportion of students capitalized on the opportunity to earn the grade they wanted. Many students, perhaps a disproportionate share compared to conventional assessment practice, chose to complete the quantity and quality of work required to earn an A in the course. Consequently, I have experimented with allowing students to choose from a variety of assignments that were worth between 50 and 60% of their grade, while the remaining 40 to 50% of their grade was mandatory and based on participation (worth 10%) and two term tests (worth 15% to 20% each). I have also considered providing students with a “menu” of assessment items and allowing them to choose any combination that adds to 100%. However, I have settled on allowing students to complete as many assignments as they want to earn the grade they want. I made this decision, because I am less concerned about the appearance of ‘grade inflation’ than I am about student voice, genuine student learning, and enhancing student engagement.

Given that students will naturally choose different combinations of assignments to match their personal strengths, interests, and skills, it is difficult for the professor to ensure all students are being evaluated against the same course learning objectives. Since students can choose different assignments and each assignment requires a different set of skills and learning objectives (e.g. writing vs. technical), it is difficult to ensure that all students, and all assignments, meet all objectives. While some of the learning objectives were co-curricular and the assessment items were designed to simultaneously assess multiple learning objectives, practitioners may find it useful to construct a matrix of knowledge, skills, and attitudes for each assignment and compare it against the course learning outcomes (e.g. using backward design). Retrospective analysis of students’ assignment choices, especially over a few years and perhaps using some clustering algorithms, should help highlight the dominant combinations of assignments. These “assignment clusters” could be used to help ensure the assignments, weighted by their point value (a function of effort), are effectively meeting multiple learning objectives.

It is noteworthy that no student avoided all the tests, and only a few students avoided more than one of the tests. Most students completed the Google Earth assignments and on-line quizzes, which, like most assignments, were scheduled to only be available when covering the corresponding class material during lectures. Some students really enjoy the international films (once 38 of 42 students showed up to an “optional” movie night), while other years only a few students show up (I often buy pizza on those nights). A few assignments, however, and typically high-value items, such as the “regional profile” and the “virtual field trip” assignments were available starting on the first day of classes and were not due until the end of the semester. Interestingly, strategic, goal-directed learners and purposeful, motivated learners (see Figure 2) quickly identified the opportunity and completed the assignments within the first few weeks. In some cases, these students quickly earned upwards of one-third of the points required for an A grade in the course. There were also students who invested considerable time and effort to meet the high standards that were communicated through instructions, an evaluation rubric, and a sample assignment. For example, one student used an analogue scrapbook to communicate the results from a “regional profile”. She used a variety of means of action and expression, such as word art, collage, cartoons, and examples of lived experience. Also interesting are students who either defiantly or distractedly chose to procrastinate and were essentially forced to complete these “big-ticket” items during the last couple weeks of class. Despite using individual grades and histograms of class grades to provide bi-weekly cautionary tales, repeated and multi-modal reminders of due dates, and other tactics, a few students did not respond to the course, the instructor, or the assessment strategy.

Assessment empowerment is not, on its own, motivating for all students. As illustrated by students’ constructive comments and anecdotal evidence from other students, many students chose to procrastinate, some paradoxically citing “choice” as part of their explanation. Arguably, all students always have a choice whether they want to procrastinate, or write a test, or hand in an assignment. Therefore, those students who procrastinated were, perhaps, not sufficiently mature, motivated, nor engaged, or they were unable to prioritize their busy schedules, or they were disengaged by some error in design, in communication, or by the instructor. Or, perhaps too many choices make it difficult or overwhelming for some students. For example, Patall, Cooper, and Robinson (2008) suggest that fewer choices tend to motivate students more than too many choices, and more than five appears to be too many. Another explanation to help explain this propensity to procrastinate may include, at least in part, students’ lack of experience playing an active role in their assessment.

I choose to implement assessment empowerment more fully in 100 and 200-level courses, but my reasoning is conflicted. On the one hand, introductory-level courses tend to be larger and, thus, tend to have a greater variety of majors, which also means they tend to have a greater variety of interests, strengths, and skills. So, introductory level courses may be the best venue for assessment empowerment. On the other hand, these courses tend to have the youngest, less experienced, and perhaps less mature students. So, introductory level courses may be the worst venue for assessment empowerment. I have also implemented assessment empowerment in an upper-level course (GIS II: Advanced Spatial Analysis); students chose the research question (and data) for their independent research project. This group of mostly seniors were more experienced, motivated, and mature, but a few students still struggled with task initiation. Of course, designing a reasonable and sound research project is a difficult task for most undergraduate, and many graduate, students.

It has become increasingly clear that students do not have a good understanding of assessment. To be fair, some academics are, perhaps, not as familiar with the theory and practice of formative and summative assessment as they should be. And, we should be able to forgive the students, since they have limited, if any, experience playing an active role in the assessment of their learning. Therefore, it is important to communicate the meaning of assessment, and perhaps provide some metacognition exercises, that allow students to: (i) explore what kind of learners they are; (ii) reflect on their individual strengths, interests, and skills; (iii) consider how they would like to express and communicate knowledge, ideas, and concepts; and, (iv) exercise their roles and responsibilities in a critical democracy.

In conclusion, most students’ comments regarding their experience with assessment empowerment have been overwhelmingly positive. These positive attitudes translate into positive attitudes toward the class and toward the instructor. These positive attitudes also translate to higher levels of academic achievement among students. Consequently, due to the enhanced student engagement, academic achievement, and positive attitudes, I firmly believe the additional work associated with implementing assessment empowerment in my classroom was effective and worthwhile.

Learn More

Where can I get additional resources?

The following resources provide additional information for readers to learn more about the pedagogical strategies portrayed in this case study.

UDL

See the CAST website for a wealth of Universal Design for Learning information that includes the version 2.0. Guidelines at http://udlguidelines.cast.org/

Differentiated Instruction

Start with Carol Tomlinson’s website at http://www.caroltomlinson.com/, which has several lesson plans, strategies, articles, and other resources available.

Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development’s website, especially the books and publications page (http://www.ascd.org/books-publications.aspx), which allows you to search, other books and resources are also available.

Critical Democracy/ Student Voice

Seminal works by John Dewey’s (1916) Democracy and Education along with Paulo Freire’s (2005) Pedagogy of the Oppressed are good places to start, but there is an expanding volume of information about student voice and critical democracy.

SoundOut has compiled a bibliography supporting their work on “meaningful student involvement” that is available at https://soundout.org/student-voice-bibliography/

Evelyn Schneider’s (1996) Giving Students a Voice in the Classroom discusses empowerment benefits associated with classroom strategies that are designed to meet students’ psychological needs. The article is available online at http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/sept96/vol54/num01/Giving-Students-a-Voice-in-the-Classroom.aspx

Student Choice (Flipped Syllabus)

A mounting body of research provides convincing evidence assessment empowerment can, for example, improve academic achievement, enhance student engagement, increase student effort, and foster students’ independence (see, for example, Francis, 2008; Dobrow et al., 2011; Pattal et al., 2010; Fulton and Schweitzer, 2011; Owusu-Ansah, 2016). While much of the research on assessment empowerment has been performed on students in public school (Weimer, 2014), there is an obvious deficiency of research on the impacts of assessment empowerment on post-secondary students (Dobrow et al., 2011; Weimer, 2012, 2014). While there may be a lack of research on choice in the college classroom, Flowerday and Schraw (2000) remind us there is literature about control and its negative impact on motivation.

John Boyer (aka Professor Plaid) allows choice using a “flipped syllabus” in his World Regional Geography class. There are several media sources that may provide more details, such as “How this teacher has flipped his syllabus online”, which is available at https://www.studyinternational.com/news/teacher-flipped-syllabus-online/

Additionally, Weimer (2014) provides insights into course design for assessment empowerment in the college classroom; it may be the best place to start.

References & Resources

Biancarosa, C., & Snow, C. E. (2006). Reading next—A vision for action and research in middle and high school literacy: A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Dobrow, S., Smith, W., & Posner, M. (2011). Managing the grading paradox: Leveraging the power of choice in the classroom. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 10(2), 261-276.

Flowerday, T. & Schraw, G. (2000). Teacher beliefs about instructional choice: A phenomenological study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(4), 634-645.

Francis, R. (2008). An investigation into the receptivity of undergraduate students to assessment empowerment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 33(5), 547-557.

Freire, P. (2005). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. (M. B. Ramos, Trans.). New York, NY: Continuum. (Original work published 1970) Retrieved from http://www.msu.ac.zw/elearning/material/1335344125freire_pedagogy_of_the_oppresed.pdf

Fulton, S., & Schweitzer, D. (2011). Impact of giving students a choice of homework assignments in an introductory computer science class. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 5(1), 1-12.

Owusu-Ansah, A. (2016). Balancing choice and control in the classroom: Reflections on decades of post-doctoral teaching. Journal of Education and Training, 3(2), 10-15.

Patall, E., Cooper, H., & Robinson, J. (2008). The effects of choice on intrinsic motivation and related outcomes: A meta-analysis of research findings. Psychological Bulletin. 134(2), 270-300.

Pattal, E., Cooper, H., & Wynn, R. (2010). The effectiveness and relative importance of choice in the classroom. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(4), 896-915.

Stan, E. (2012). The role of grades in motivating students to learn. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences. 69, 1998-2003.

Tomlinson, C. A. (1999). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Tomlinson, C.A. (2003). Fulfilling the promise of the differentiated classroom. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Tomlinson, C.A. (2004). Sharing responsibility for differentiating instruction. Roper Review, 26, 188.

Weimer, M. (May 16, 2012). Giving students choices on how assignments are weighted. From website: Faculty Focus: Higher Ed Teaching Strategies from Magna Publications. Retrieved from http://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/teaching-professor-blog/giving-student-choices-on-how-assignments-are-weighted/

Weimer, M. (February 20, 2014). Adding choice to assignment options: A few course design considerations. From website: Faculty Focus: Higher Ed Teaching Strategies from Magna Publications.

Additional Resources

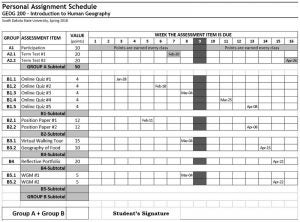

This section contains two resources that were mentioned in the body of the case study. Resource #1 is an excerpt of assessment empowerment instructions from the syllabus. Resource #2 is a copy of a Personal Assignment Schedule, from a different course, that was used to help (i) mitigate the tendency of some to procrastinate, (ii) codify students’ assessment choices, and (iii) plan their respective due dates.

Resource #1 – Assessment Items and Procedures

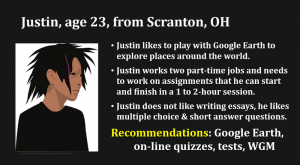

This section contains an excerpt from the “instructions” section of the course syllabus, which includes a descriptive preamble to this unconventional assessment strategy. The syllabus is presented on the first day of classes, and the focus is mostly on assessment. Each item is described to help explain the types of assessment items that students should choose to reflect their personal strengths, interests, and skills. To provide further information, each assignment’s rubric is presented and explained, a sample completed assignment is illustrated, and students are shown where they can access this information on the LMS. Furthermore, there are slides to illustrate alternative “scenarios” and some of them (Figure 4, for example) illustrate a sample combination “scenario” that based on a students’ strengths, interests, and skills.>

Figure 4: Recommended Combination of Assignments Sample Slide

A recent addition to my routine are “personal assignment schedules”, which I hand out to students on the first day of class. I illustrate (often using think-aloud demonstrations) how to complete the assignment schedule. Then I have the students choose a single assessment item that they will most likely complete and have them enter it into their personal schedule. Fully completed and signed personal assignment schedules are required from all students. I review the schedule, make personalized comments that are based on their choices, assign one extra-credit point toward their final grade, and then return it to the student at the beginning of next class. As a continuing reminder of their progress in the course, their cumulative grade is available in the LMS, I regularly show a histogram of class grades and pass around a list of student numbers and grades at the beginning of class to ensure they remain aware of where they stand, both in the course and against their peers.

Assessment Items and Procedures

This course may be described as “unconventional” when it comes to my proposed approach to assess student learning. Rather than the common approach of having a set of required activities (e.g. 2 tests and 1 term paper), I provide you a variety of different options that you can choose to earn points towards your grade. This approach allows you to choose a combination of assignments that capitalize on your individual interests and strengths.

This approach is based on the idea of a “critical democracy”; students can choose what that want to work on, and they are able to earn points by completing different activities until they achieve their desired grade. If you excel at writing tests, then you should write lots of tests. If you are good at writing papers, then choose to write lots of position papers. I recommend that you complete a variety of different assignments, but make sure that earn enough points to get the grade your want. Yes, everyone can get an A under this approach. However, it is important to note that just because an assignment is worth 30 points, your assignment will be graded so if you score 50% you will earn 15 points (30 points x 50% = 15 points).

WARNING! It is also very important for you to understand that you, and only you, are responsible for earning your final grade. There is only one way that you can mess this up, and that is to keep putting things off until the end of the semester. It WILL NOT WORK if you wait until the end of the semester and try to make up for procrastinating all semester. Most of the assignments have weekly deadlines, and THERE ARE NO “MAKE-UPS”, or extra-credit assignments at the end of the semester to earn points. So, it is your responsibility to choose the assignments and plan your semester wisely!!!

When choosing the assignments that you want to complete, you are free to complete as many different assignments as you choose to achieve the final grade that you want in this course.

| Assessment Item (n available) | Points Toward Final Grade | Maximum Score |

|---|---|---|

| Participation | I will drop your lowest 5 scores (absences) | 10 points |

| Chapter Quizzes (x 11) | 2 points each (+3 for completing at least 10) | 22 points |

| Term Tests (x 4) | 10 points each (+3 for completing all 4) | 40 points |

| Google Earth Exercises (x8) | 3 points each | 24 points |

| Position Papers (x6) | 6 points each (+3 for completing at least 5) | 36 points |

| Regional Profile (x1) | 30 points each (1 maximum) | 30 points |

| Virtual Field Trip (x1) | 30 points each (1 maximum) | 30 points |

| Why Geography Matters (x2) | 5 points (2 maximum) | 10 points |

Participation (1) It is important to regularly attend class and actively participate in class discussions and exercises. I will be using REEF Polling by i>clicker in class this term. REEF Polling helps me to understand what you know, gives everyone a chance to participate in class, and allows you to review the material after class. Therefore, you will need to create a REEF Polling account to vote in class using your laptop, smart phone, or tablet connected to the university’s Wi-Fi. Go to http://reef-education.com or download the REEF Polling app and sign up for a REEF Polling account. You should use your university email address and your Student ID in the Student ID field. If you need to change your email address, password, or student ID, edit your account profile. Do NOT create and use more than one REEF Polling account as you will only receive credit from a single account. You will need to purchase a subscription to use REEF Polling. Creating a REEF account automatically starts a free 14-day trial subscription.

Chapter Quizzes (11) As we complete the readings and lectures for each chapter, an on-line quiz we be made available through Connect. The quiz may be completed for one week only following the completion of each chapter. The quiz will be made up of multiple-choice and map identification questions that directly pertain to the material covered in the assigned readings and lectures. Students are expected to complete the quizzes individually and will have more than one attempt to complete the quiz.

Term Tests (4) Term Tests will be administered throughout the semester (see the Proposed Lecture Schedule for dates of each test). Each will be written in class and will cover all lectures, readings, and discussions. Therefore, it is important to read the material, attend class, and complete assignments. The test will consist of multiple-choice and short-essay questions that may refer to figures, tables, or diagrams discussed in class or from the textbook. If you choose not to write a specific test, you are excused from class that day.

Google Earth Exercises (8) Google Earth is probably the most accessible, easy-to-learn map making software available to students and teachers. Many, if not most, students are already familiar with Google Earth. Google Earth is a geographic information and visualization program that superimposes spatial data onto a dynamic three-dimensional globe, which allows us to explore the planet from our computers. If you have not done so already, you must first download a copy of Google Earth to your computer. If you are unable or unwilling to get Google Earth running on your computer, you are welcome to use one of the Geography Department’s GIS computer labs. If you are totally unfamiliar with the software, or you have limited experience using it, begin by accessing Google’s Online User Guide. It can be found on the help menu. Additionally, there is plenty of detailed information amiable on YouTube about specific Google Earth topics. Once you have Google Earth loaded on your computer and are familiar with navigating the software, you are asked to answer a series of questions in the form-fillable assignments that are available on the course D2L site.

“Movie Night” Position Papers (6) There will be a series of 6 movie nights throughout the course. The movies will be screened on alternating Wednesday evenings starting at 6:30pm (the final schedule and list of movies will be posted on D2L and announced in class). The purpose of the position paper is to provide an opportunity to discuss emerging topics without the experimentation and original research normally required for an academic paper. Commonly, a position paper attempts to argue a position (opinion) with supporting evidence. Position papers require you to concisely articulate the arguments provided by the film you have watched. This helps you to become a more active participant, which means that you look for clues and ask questions as you watch rather than simply just accepting any director’s argument. Also, by thinking about and effectively, or persuasively, communicating an argument in writing (the art of rhetoric), you are doing the work that is essential for many jobs and for exam preparation, because both your employer and professor often require you to assess questions and arguments and further analyze them. Position papers also help me assess how you are doing in the course, because they allow me to see how well you are making the connections and understanding the videos. Position papers are expected to 3 pages in length (not including title page and bibliography), double-spaced, 12-point font, with 1-inch margins. All bibliographic sources must be cited in the report and follow a consistent style (Chicago, MLA, or APA) See instructions and evaluation rubric for more details.

Regional Profile (1) Students are expected to write a report (8-pages, double-spaced, 12-point font, with 1-inch margins), inclusive of pictures, maps, diagrams for any one region covered during this course. Once you have chosen your region, you will need to develop a “profile” that describes the 5 major themes of geography. The report should outline the physical geography, demography, historical geography, economic geography, cultural geography, and environmental issues associated with that region. Central to this report is how these aspects of the region interact to shape the region’s character and “sense of place”. It is important to include maps, photos and diagrams (where appropriate) to help illustrate the various aspects of the regional profile. The bibliography must include a minimum of six academic sources and all sources must be cited in the report and follow a consistent style (Chicago, MLA, or APA). See instructions and evaluation rubric for more details.

Virtual Field Trip (1) A virtual field trip is like a field trip to an actual place, but instead of physically visiting that place it uses internet (i.e., virtual) resources to visit a place of interest in order to accomplish specific educational objectives. The purpose, or educational objective, of this virtual field trip assignment is to provide opportunities for students to get a feel for a place and gain a sense of what the place is like without actually being there. Furthermore, the purpose of preparing a virtual field trip is to provide students with hands-on experience working with multimedia files and both developing and delivering a presentation. Each student is expected to (1) develop an outline, (2) create a virtual field trip in MS Power Point, Google Earth, or other format, and (3) deliver a 15-minute presentation for the class (alternative arrangements are possible). The virtual field trip can be based on any region covered in this class, but it must be different from all other students, so regions are assigned on a first-come-first-served basis. This is a major project worth a significant proportion of your final grade, so it is important that you do not fall behind. The bibliography must include a minimum of six academic sources and all sources must be cited in the presentation and follow a consistent style (Chicago, MLA, or APA). See associated instructions and evaluation rubric for more details.

Why Geography Matters (2) Because everything happens or exists somewhere, we can study or consider how it’s unique geographic occurrence affects it or other phenomena, including us, or how it differs from similar things elsewhere. Hopefully, this and other geography courses you take at university will change your mind about what geography is, how it is relevant to you and society in general, and Why Geography Matters. Hopefully we will discuss a topic in class, you will attend an event on campus (these will be announced on D2L “updates” and in class), or you will read or hear something in the news that makes you think about how and why geography matters. Your assignment is to write a short essay (two pages, double-spaced, 12-point font, with 1-inch margins), explaining (a) what it is and (b) why and/or how it is a good example of Why Geography Matters. See instructions and evaluation rubric for more details.

Resource #2 – Personal Assignment Schedule

developed for another course (GEOG 200) in which I used assessment empowerment. It is noteworthy that this course used required, Group A, assessment items (two tests and participation) collectively worth 50% of their final grade. The other half of their grade, or more accurately up to a maximum of 50 points (of the 99 available points) toward their final grade, are optional, Group B, assignments. The purpose of the personal assignment schedule is to have students consider, reflect, and create their own assessment plan that matches their personal strengths, interests, skills, and schedule for the semester. It is noteworthy that some students may require a few minutes of individual attention to help appropriately choose and plan their assessment schedule. The personal assignment schedule is signed by the student and submitted to the professor. I approve the schedule, comment on their choices, and hand it back to the student the next day. I choose to incentivize the process by awarding 1 bonus point for taking the time to complete the schedule.

About the Author

Jamie Spinney

Jamie Spinney is an Assistant Professor at South Dakota State University. He is a teacher-scholar who is best described as a broadly-trained geographer, with professional training as a high school teacher, an adult educator, an urban/ regional planner, and a geomatics specialist. Guided by his pedagogical training and influenced by his varied teaching experiences, his journey toward teaching excellence includes the scholarship of teaching and learning. For example, he is actively investigating student engagement, technology in the classroom, and applications of assessment empowerment. He is also interested in the role of inquiry-based experiential teaching for enhancing undergraduate and graduate instruction.