Classroom Response Systems

Contents

- Introduction

- UDL Alignment

- Instructional Practice

- What is a Clicker?

- Getting Started with Clickers

- Using Clickers in Your Classroom

- Taking Attendance

- Checking Student Preparation for Class

- Increasing Engagement and Interactivity

- Providing Formative Assessment for Students

- Testing

- Teaching Students about Using Clickers

- Possible Problems Associated with Using Clickers

- What do students say about clickers in SOIS comments?

- Other student response systems

- What Students are Saying

- Summary

- Learn More

- References & Resources

- About the Author

Introduction

Faculty members in college classrooms today often find themselves teaching large sections (100 plus) of students, especially in introductory classes. For some content areas, the challenges associated with teaching large numbers of students in each class extend throughout post-secondary programs. Balancing instructional needs, such as documenting student attendance, maintaining student engagement, evaluating student understanding of class content, and grading/providing student feedback efficiently and effectively can prove extremely challenging. Clickers (classroom response systems) can provide one technology that faculty members teaching large numbers of students can use for addressing these instructional components. A clicker is a handheld wireless device that resembles a small remote control. It transmits to receivers via infrared or radio signals, sending results to the professor’s computer. Basically, clickers allow rapid collection and analysis of student responses to questions presented by the instructor. The questions used to prompt students’ responses can be strategically selected by the instructor to serve a variety of purposes. Clickers may also be helpful in smaller sections for increasing interactivity and for formative assessment.

At East Carolina University, several faculty members, teaching across a range of content areas, use clickers in the classroom and have provided ideas and suggestions based on their experiences for this module. Dr. Karen Mulcahy (Geography), Dr. Grant Gardner (Biology), and Dr. Subodh Dutta (Chemistry) teach a range of introductory courses offered to large numbers of students, and their primary reasons for using clickers are to keep the students engaged, to increase interactivity, and to maintain opportunities for formative assessment. For some, this means using clickers to take attendance via brief clicker quizzes given at the beginning of class to prime students’ background knowledge and refresh memories from previous classes. For others, it means conducting a quick formative assessment to provide a starting point for class lecture/discussion and to quickly record student attendance. Using clickers with small group activities in a large class provides another way to engage students in active learning with the content and to measure student understanding of key class concepts. Some instructors use clicker questions to poll throughout the class period to increase students’ engagement and to provide formative assessment data.

Mr. Bob Green (Nursing) and Dr. Janice Neil (Nursing), who teach junior and senior students, have highly motivated, engaged learners; yet, clickers also play an important role in their classes. Dr. Neil uses clickers to administer a brief quiz at the beginning of class on material covered during the previous class period, providing a quick way to take attendance and assess learning. For Mr. Green, clickers are used for formative and summative assessment in his classes. In addition to the quick quizzes at the beginning of class, he interjects clicker polls throughout the class, and even administers all course tests with clickers. He also administers all of his exams using clickers. Knowing that students in today’s college classrooms grew up with and are comfortable using technology, he seeks to incorporate these resources, when appropriate, to support student learning.

Read more in the Instructional Practice section of this module about the ways these faculty members use clickers in their classes and their suggestions for new adopters of this technology. Continue reading to learn about the use of clickers in smaller classes and in online classes.

UDL Alignment

Each College STAR module will explain how a particular instructional practice described within the module aligns with one or more of the principles of UDL. For this module, the focus will be on Provide Multiple Means of Representation, Principle I; Provide Multiple Means of Action or Expression, Principle II; and Provide Multiple Means of Engagement, Principle III.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Representation

Using clickers in class aligns with the UDL principle of Provide Multiple Means of Representation in several ways. For example, faculty members may choose to focus on “big ideas” or the most critical information in clicker questions. This, in itself, helps make the key ideas and most important concepts more salient to students, and presenting them in question form enables students to think about how this information might be applied or even assessed. Also, aggregated summaries of student responses to a “clicker poll” are often displayed to students in graphic form. So, simply incorporating this resource into a discussion provides both an auditory (based on class discussion) and a visual/graphic format (clicker poll summary). Instructors can further enhance the variety of ways in which students receive and interact with information by making instructional choices about what to do with information from a poll. For example, conducting a clicker poll may be followed by interactions such as: (a) turn to a neighbor and discuss which response is correct and why (Think-Vote-Share), (b) facilitate a class discussion about which response is correct, or (c) use Mazur’s “Peer Instruction” model (Mazur, 1997) for small groups. With Peer Instruction, in predetermined small groups, each member attempts to explain why his or her response is correct, followed by another polling of the class. These discussions help students to focus on the “big ideas” and to develop conceptual understanding.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression

Using clickers can also address the principle of Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression. Clickers can supplement the other modes of expression (i.e., class discussions, short answer exams, papers, presentations, etc.) used in classes. When different types of clicker questions (e.g., multiple choice, true/false, matching, short answer, and opinion vs. fact-based questions) are included within the class, students are provided with alternate ways to demonstrate understanding. Instructors often find that very few students in large sections ask questions during class or respond orally to questions posed by the instructor. Consequently, the instructor has access to limited information about the level of understanding within the class. Formative assessment conducted with the use of clickers enables all students to respond to all questions, resulting in a dramatic increase in student comfort with responding and in the amount of information the professor has about student understanding. Using clicker questions is often followed by class discussions or peer instruction, which offers more opportunities for expressions of understanding. Additionally, students are able to compare their responses to those from the rest of the class and more accurately monitor their own progress in learning the content compared to their peers. Students receive immediate feedback after tests when responses are given with clickers. And an added benefit for the instructor is the dramatic reduction in time required for grading!

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Engagement

Student engagement may be the most commonly reported reason for using clickers. Clickers can be used to build variation into class routines by addressing the Principle of Multiple Means of Engagement. For example, interspersing clicker questions builds in a periodic change of pace and helps students to maintain focus on the class content. When clickers are used periodically during a class to ask questions or poll for understanding, students receive immediate and specific feedback about their level of understanding in relation to the class lecture. Additionally, using clickers for small-group activities can be another way to keep students engaged by providing a different type of interaction with content and classmates. Likewise, the small-group interaction enables students to discuss and explain concepts, which is helpful for moving from memorizing facts to developing conceptual understanding.

Instructional Practice

This module covers information about uses of clickers which are clearly linked to the UDL principles of Multiple Means of Engagement, Multiple Means of Action and Expression, and Multiple Means of Representation. As you read the following description, please think about how you might use clickers in your content area.

What is a Clicker?

Clicker systems include both student and faculty components. Students usually have hand-held devices that enable them to select a letter or number to respond to a question presented by the instructor. The instructor utilizes a receiver, software, a laptop or other computer, and a storage device (i.e., flash drive or external hard drive). Each student’s response is sent by radio waves to the instructor’s receiver, and the software analyzes responses to generate a response record and display the distribution of student responses (e.g. on a bar chart). The instructor has access to this information immediately, and can use the student response summaries to make ongoing instructional decisions. The storage device enables the instructor to save and move the data to another computer after the class session is over.

Several companies manufacture clicker systems. Among these are Turning Technologies and iClicker. Although the basic components are the same, the configuration of specific options does vary with different clicker products.

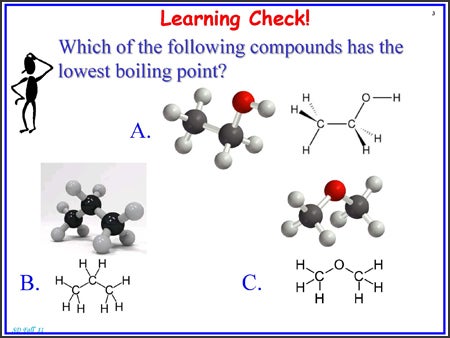

The instructor can insert clicker questions into a PowerPoint presentation or poll with oral questions. When slides are used, the question and possible answers are presented. Students use their clickers to select the correct response. Figure 1 below is an example of a clicker question on a PowerPoint slide. The slide shows the question prompt, “Which of the following compounds has the lowest boiling point?, followed by three possible responses with the compounds represented graphically but not named. The students will select A, B, or C on their clickers to indicate their answer.

Figure 1: Example of a PowerPoint Slide with a Clicker Question

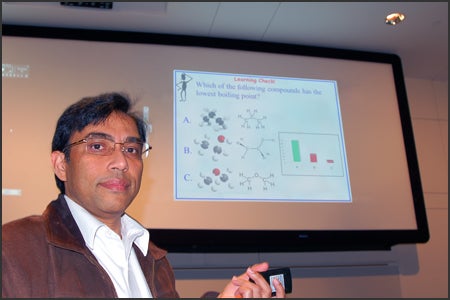

Once students have viewed the clicker question and registered their responses using their individual clickers, the system aggregates the responses and generates a graph showing the distribution of responses to the question. This bar graph of response distribution then appears on a new slide with the question and possible answers. The photograph below, Figure 2, shows Dr. Dutta and the slide, illustrating the question, possible answers, and the distribution of responses.

Figure 2: Dr. Dutta with a slide showing a question, possible responses and response distribution.

The video clip shown below “Students and Teachers Speak: Clickers in the Science Classroom – Why Use Clickers?,” (CU-SEI & CWSEI, 2009) provides an overview of the ways that clickers are used in some classrooms, from both the instructor and the student perspective. It provides an opportunity for you to observe the components and action of the clicker system and to link the use of clickers to information you read in the UDL Alignment section of the module. Be sure to listen to what faculty and students say about the presentation of information (representation), active involvement of students in demonstrating learning (action and expression), and student engagement as they tell about their classroom experience with clickers.

Getting Started with Clickers

In many cases students purchase their own clickers through the student bookstore or other designated source and register the clicker with their course management system (e.g., Blackboard). In other postsecondary settings, the school or department purchases a set of clickers to be used in the classroom. Although it is possible to allow anonymous responses for aggregated data, most instructors seem to prefer that students register their clickers. Registration of the clickers enables an instructor to know which students are responding, and, of course, identifying students is essential if the instructor wants to use the clicker system for taking attendance, giving quizzes, or receiving test responses. The bar chart created by the clicker system software presents the responses anonymously, providing a safe way for all students to respond without raising their hands or speaking their response. If needed or desired, instructors can follow up with individuals who are consistently struggling with correctly responding to prompts.

If you as an instructor are considering using clickers for the first time in your classes, it is important to consider your school’s policy about clicker use, as well as the training and support available for faculty. Each school will be different, but Dr. Wendy Creasey and Ginny Sconiers in the Department of Academic Computing at East Carolina University share information and links to resources for ECU faculty members who want to begin using clickers in their classes. Though your school may have different policies, we hope this information will provide ideas you may need to consider obtaining from your school.

ECU CLICKER INFORMATION FOR FACULTY at East Carolina University, Turning Technologies Response Card NXT is the recommended and supported audience response device. Students can purchase this product through the Dowdy Student Stores.

Support is provided through the central and decentralized IT staff at the university. For more information on integrating audience response systems in your courses, faculty members are instructed to contact the Instructional Technology Consultant (ITC) for their Academic Unit. Unit ITCs can help provide faculty with the information they need to start using clickers in the classroom as well as help show them how to use the Turning Point software.

Below are sample instructions and resources that are shared with ECU faculty to promote successful integration and support of these tools:

Contact the IT Help Desk for assistance at 252.328.9866/1.800.340.7081 or submit a help ticket at https://ithelp.ecu.edu/. More information can be found in the ITCS Service Catalog. In addition, Turning Technologies has an array of resources and videos to help instructors decide which features fit their particular need. Visit the Audience Response Support page to access helpful online tutorials, training documents, webinar archives, and more.”

Dr. Wendy Creasey and Ginny Sconiers, ECU Academic Computing

In addition to the written description above, training opportunities are provided for faculty through ITCS and the Office for Faculty Excellence. Even if you are not teaching at ECU, you would likely find information in the ECU ITCS Service Catalog and in the videos at the Turning Technologies Audience Response support site that would answer specific questions you have about using clickers.

Using Clickers in Your Classroom

If used effectively, clickers can address the following five of the seven principles of good instruction in undergraduate education described by Chickering and Gamson (1987):

- Encourages contact between students and faculty

- Develops reciprocity and cooperation among students

- Encourages active learning

- Gives prompt feedback

- Emphasizes time on task

The following descriptions of strategies used by faculty members illustrate how instructors are implementing the use of clickers in their classrooms to address these principles and to increase student learning. These strategies are simply examples, and are included here to stimulate your thinking about your own classroom environment. Naturally, each activity (e.g., taking attendance or using clicker polls) can be modified or used for more than one purpose.

Taking Attendance

(Potential Additional Benefits: Conserving Instructional Time and Gathering Formative Assessment Data)

Most instructors believe (and some research literature supports) that student attendance is critical to successful completion of courses (Clark, Gill, Walker, & Whittle, 2011; Gump, 2005; Lyumbartseva & Mallik, 2012; Newman-Ford, Fitzgibbon, Lloyd, & Thomas, 2008). Dr. Dutta has gathered data to look at the impact of attendance on course outcome for students in his large (200 plus) chemistry sections and has found that attendance is, in fact, a predictor of students’ final grades. At the beginning of each semester, he explains to students that the course concepts will build from class meeting to class meeting, so that missing even one day of class will impact understanding in future classes. The formative assessment data he gathers through clicker polls help him to identify students who may be at risk and need extra assistance to succeed in the class, prompting him to provide additional examples to clarify the material.

Many faculty—including Dr. Dutta, Dr. Mulcahy, and Dr. Neil—feel that taking time to “call the roll” reduces much-needed instructional time. Instead, all of these instructors begin class with a brief clicker quiz covering key points presented during the previous class. At the time the class is to begin, the instructors present the quiz via PowerPoint slides, and students respond by using clickers. The data from the quiz is saved by the instructor, noting which students are present and creating a record of student responses. It is possible to view the record of responses to clicker questions posed throughout the class period to know when a student arrives late, providing an even more accurate record of attendance. Students may receive points for being present and responding to the clicker question at the beginning of the class as well as additional points for having the correct answers. Of course, the attendance quiz also provides a quick check, or formative assessment, to be sure students understood the information from the previous class.

Instructors may choose how to use the information gathered through this resource. For example, some instructors choose to show the bar chart for each question so all students can see the aggregated data and compare their own responses to the responses of the class. The instructor can easily assess the graphs to learn whether there are concepts that must be reviewed or retaught in another way before the group can proceed and if there are students who might need individual instruction or support from the tutoring center.

Instructors can follow up with students who miss class (as recorded by clicker quizzes), via emails, or other contact methods. A brief email reminds a student about the importance of being in class and lets the student know the instructor has an interest in the student’s success in the class. This is a quick and efficient way to make a student connection, increase a sense of student accountability, and possibly make a critical difference in student performance and/or retention.

Using clicker quizzes to take attendance saves instructional time and provides formative assessment data for the instructor. Yes, taking attendance may impact the decisions of some students regarding whether or not to come to class, but when using clickers, taking attendance becomes so much more.

Checking Student Preparation for Class

(Potential Additional Benefits: Gathering Formative Assessment Data and Taking Attendance)

Dr. Gardner and Mr. Green give brief clicker quizzes at the beginning of class that not only gather attendance data, but also provide information about whether students have prepared for class. These quizzes contain four or five questions based on the assigned readings. Dr. Gardner feels this practice reiterates his message to students that he is not a “human highlighter” and will not be presenting the material they were to read prior to each class. Gardner says, “We’re going to be engaging in the material—working with greater concepts. So you better have the vocabulary walking in the door.” Dr. Gardner may not give a quiz every day, but knowing that the points from these quizzes are a part of their grades may encourage students to take a look at the readings and come prepared. For Gardner, having students prepared to move forward with major concepts allows him to incorporate small-group activities in his large (200+) class sections to increase engagement and active learning.

Clicker quizzes about assigned reading provide attendance data and encourage students to come to class prepared for the topic to be discussed, freeing valuable class time for group activities and a focus on conceptual understanding.

Increasing Engagement and Interactivity

(Potential Additional Benefits: Gathering Formative Assessment Data and Incorporating Small Groups)

All of the faculty members who provided information for this module mentioned using clickers to increase student engagement and interactivity. This applied especially to first-year students, students in large sections, and students who may be reluctant to speak up in class. Interactive technology, such as clickers, can help engage a classroom full of unresponsive students (Guthrie & Carlin, 2004).

One of the reasons Dr. Mulcahy chose to use clickers was to increase interaction and engagement in her classes. Despite her earlier attempts to engage the students in discussion, they would just “sit there”—not responding or actively participating in class dialogues. If students did respond, they were usually the same few students. For this instructor, clickers provide a system that allows all students to answer every question and to do so in a way that their individual responses are not identified to others in the class. Therefore, using clickers makes it safe for the students to respond, since they do not have to raise their hands or have others hear their responses. Mulcahy now uses responses to clicker question polls as the participation grade for the class. Students get two points if their response is correct and one point if the response is not correct. Dr. Mulcahy says, “It has enabled more engagement from each student. I’m better able to judge whether or not they understand a particular concept. That feedback is invaluable in trying to explore the concepts because they won’t tell you if they don’t understand.” Mulcahy notes that as the students in her class become accustomed to interacting via clickers, it starts to create a more vocal, more interactive environment where students begin discussing content with their peers.

The video clip below titled “The Anatomy of a Clicker Question: Clickers in the Science Classroom,” [transcript] (CU-SEI & CWSEI, 2009) provides a brief introduction to clicker questions across several content areas. As noted in the video by both instructors and students, clicker questions are most effective when challenging, conceptual questions are used and followed by discussion.

When planning for class and creating his PowerPoint slides, Dr. Dutta intentionally writes questions to insert for clicker polls every 10 to 15 minutes of the class period. Regularly giving students questions to answer helps keep them engaged, provides them with feedback about their responses, and provides a real-time formative assessment for the instructor. Without this type of formative assessment in large sections, the instructor would not know if students were struggling or grasping the concepts. The clicker questions can be used to prompt a brief discussion or provide an opportunity to clarify. It takes Dr. Dutta about two to five minutes to write a poll question, depending upon the type of question. The few minutes it takes him to generate and insert lecture questions pales in comparison to the increased student engagement and feedback opportunities. Naturally, questions can be developed prior to class and even inserted in the PowerPoint presentations, but they also can be inserted spontaneously during a class discussion. Mr. Green uses both types of questions during class, adding oral questions as needed to immediately poll the students on an issue presented during the class instruction.

Mazur’s Peer Instruction model (1997) is among the group activities Dr. Gardner uses in his large sections (200 plus) to enable students to engage with the content in multiple ways. Gardner will display a clicker poll question, have all students respond, present the bar chart showing the response distribution, and then have the class divide into their predetermined groups. In their groups, students discuss the question and try to explain their thinking processes regarding their selected answer. Each group member defends and explains his or her answer, and then the same clicker poll question is presented again. At this point, the instructor may reveal and discuss the correct answer or ask students to explain the concept. This process actively involves students and incorporates peer descriptions of class concepts. By using the clicker responses from all students rather than only from a group leader, the instructor knows which students are still not grasping the concept.

This flash video clip [2.20 min.] by Dr. Bill Reay from Ohio State University, gives a brief description about the way one professor uses clickers with groups in his large sections and his reasons for choosing clickers.

Using clicker polls during class increases student engagement with the content, provides formative assessment data for the instructor to assess the level of understanding of each student in the class, and these polls can facilitate the use of small group discussions during class to enhance conceptual understanding.

Providing Formative Assessment for Students

Dr. Gardner suggests that in addition to collecting formative assessment data to inform instruction, it is also important for students to gather formative assessment data about their own performance. Students may find it challenging to gauge their level of understanding in a class— especially during a lecture that seems to be making sense at the time. Instead, it may only be once students are expected/required to interact with and apply class content that they realize they lack understanding. When a clicker poll question is presented and the bar chart of aggregated data is on the screen, students get a clear picture of how they are doing in relation to the rest of the class. Gardner says, “If the graph flashes up that 60 percent of the people got it right, I think to them it is an honesty check.” The student might be thinking she knows that material but realizes she doesn’t understand it and really needs to review the information. Likewise, if 60 percent got the wrong answer and the student was one of those, she might realize that, though she selected the wrong answer, she is not too far behind others. “So for them, it’s a kind of interplay of what they understand and also what the class understands. It helps them, again, feel part of this larger group of the class,” Gardner says. There can be some level of comfort in knowing how they compare to the group, especially when students may be feeling they are the only people who do not understand. Of course, it is what students do with this formative assessment that makes the real difference in learning. If this information causes the students to review something they thought they understood, more learning will likely occur.

Showing the bar chart generated following clicker poll questions provides information each student can use to assess his or her own understanding relative to the total class. This can provide a critical reality check for some students.

Testing

Dr. Mulcahy and Mr. Green have their students use clickers to complete all testing within their classes, and they view this as a huge timesaver for grading and posting grades. Grading is completed automatically by the clicker system so students know their grade before they walk out the classroom door. Grades can then be uploaded directly into the Blackboard gradebook. Mulcahy likes the ease of uploading clicker-collected grades and encourages other faculty to try it.

Instructors who use clickers for tests can view data overall or even by responses to individual questions. So, instructors can obtain test data for item analysis that is critical for ensuring that test questions are accurately assessing student understanding of class materials. For example, using item-analysis, an instructor could notice that student responses for a particular question are pooled around two answers, go back and review those two choices, and decide if both answers might actually be acceptable. If the instructor decides credit should be given, he or she can make a quick change in the grade. This is a basic example, but more advanced forms of analysis are available with some clicker systems.

Mr. Green and Dr. Mulcahy shared that, for now, the clickers they are using are only useful for multiple-choice or true/false testing. Typing short answers or essays would be very time consuming, requiring a student to tap a button multiple times to get to the desired letter, much like texting on older cell phones where each key represented more than one letter. This may change as technology advances.

Questions often asked about testing with clickers include

- How do you control for cheating?

- What happens if the system crashes or if a student questions the grade?

- Does it take more instructor time?

How do you control for cheating? Instructors interviewed for this module employ several strategies to preclude cheating. For example, the letter image on the clicker display is rather large and might be seen by someone sitting beside a student. To help with this problem, Mr. Green creates two versions of his tests, and students enter the version number on their clicker before they begin the test. Alternating distribution of test versions can deter cheating via copying from one’s neighbor. Another issue is the possibility of students stepping out of the classroom and then changing their answers. It may be possible for them to walk right outside the door, and quickly look up and change a response since the answers are sent by a wireless signal. It is important to be certain students click “submit” on their clickers before leaving the room. Green requires that students show him their clickers to be certain they have submitted the responses when they hand him the printed test questions on their way out of class. With this approach, he knows the grade, the student knows the grade, and the student cannot make any changes.

What happens if the system crashes or students question the accuracy of the grade? How do instructors assure students that the grade they receive for a clicker test is accurate? Dr. Mulcahy suggests that a backup plan is critical and encourages first-time faculty users of clickers for testing to have students mark test answers on a bubble sheet and enter the answers using the clicker. This redundancy ensures that student answers are recorded even if a glitch in the technology happens during testing, while the instructor becomes more comfortable addressing potential technical challenges.

Even though he has considerable experience with this form of instructional technology, Mr. Green always uses a back-up system when testing, simply because of the high-stakes nature of all testing for his students. He gives students a printed copy of the test on which they write their responses prior to submitting the selections via clickers. In the event of technical challenges with the clicker system, he arrives on test day with plenty of backup bubble sheets. Even if no technical difficulties arise, this system offers an additional safeguard for students. If a student feels that his or her clicker wasn’t working correctly during the test (or that he or she might have made a coding mistake), Green can compare the marks on the printed test to the responses recorded by the clicker system. For most students, the backup system reduces test anxiety that may be associated with the extra (and technological) coding layer. For others, knowing the professor has both records may tempt an effort to “game the system” by putting one answer on the printed test and entering the other in the clicker on questions where they have only been able to narrow down two of the possible answers. Mr. Green ensures that students understand that if there are discrepancies between the printed test and clicker responses, the printed test with written responses will be the “gold standard,” the response used for grading. Dr. Neil also emphasizes the importance of deciding up front what the “gold standard” will be for the class if clickers are used for testing. Setting the ground rules up front does away with any disagreements regarding each student’s grade.

Time is always a consideration for instructors challenged with covering required course content in a brief, semester-long time frame and providing student feedback sufficient to build understanding throughout the semester. When asked if clickers helped him to be more efficient with what often seems like endless grading, Mr. Green candidly responded that his first semester testing with clickers was challenging. He strongly suggests having a good backup plan for recording responses on assessments. Now that he is more comfortable with the clicker technology, however, he finds that it saves a tremendous amount of time with grading and helps provide the data needed for a clearer picture, not only of overall class performance, but by illustrating how individual students in his large section are doing.

Having students use clickers to enter responses on tests reduces the amount of time the instructor must devote to grading; time that instead can be spent analyzing the responses and making future instructional decisions accordingly.

Teaching Students about Using Clickers

It isn’t enough to require your students to purchase clickers and bring them to class. If you want students to understand the importance of using clickers, you need to explain to students why you chose the clicker technology. Help them to understanding how learning takes place.

The video, “Explaining to Your Students Why You are Using Clickers,” [transcript] (CU-SEI & CWSEI, 2009) describes the importance of and ways to prepare students for use of clickers in the classroom.

Possible Problems Associated with Using Clickers

- Accessibility may be a challenge for some students with disabilities who are enrolled in classes where clickers are being used.

- Consider accessibility features of the clicker technology you use in your classes and of the accommodations students need in order for the playing field to be level. Review the accessibility features of the clicker system you select. This information should be available on the company’s website.

- If student response using clickers is a requirement in your grading scheme, pursue other alternative-response formats. Some students may be able to select the correct response on a clicker if the instructor reads aloud the questions and response options. Some students with physical disabilities may be unable to hold a clicker or press the keys. Consider other options such as response cards or alternate keyboard entries. Talk with people in the Office of Disability Supports on your campus to learn about possible alternatives that align with student response systems.

- Not all students in the class will purchase clickers and bring them to class, which limits participation and feedback.

- Some instructors have a few spare clickers to lend to students when needed.

- Instructors who assign points for clicker questions might consider dropping a certain number of days of clicker use in case students forget to bring their clicker or experience technological problems, such as having a dead battery.

- In some ways, this failure to purchase clickers is no different than the fact that some students do not purchase the textbook for class. Not purchasing a clicker may be related to insufficient funds to purchase the textbook and/or clicker. If so, making the clicker required for class means that financial aid and/or scholarships can usually be used to cover the cost. It is also suggested that instructors inform students that clickers are a long-term investment and may be useful in future courses throughout their program of study.

- It takes time for faculty to get comfortable with using the technology.

- A learning curve is associated with technology any new instructional approach. Each instructor will need to decide if the time saved in grading quizzes and the increased formative assessment aspect outweigh the time necessary to learn the technology.

- Sometimes technology does not work; at that point, instructors must continue with class and teach.

- There may be times when the clicker technology does not work, a lightbulb on the projector burns out, or there is an electrical outage. As with any instructional tool, each instructor will need to decide if these rare occurrences outweigh the usefulness of the clicker system.

What do students say about clickers in SOIS comments?

Some student comments support the usefulness of this technology:

- Some students say clickers help them to learn more.

- When questions that are similar to clicker polling questions used in class appear on a test, students have remarked that they got the test question right because the in-class questions prompted them to review material they had not previously understood.

What does data gathered across several semesters show about the impact of clicker use for one of the instructors who contributed to this module?

Since beginning to use clickers several semesters ago, Dr. Dutta reports an increase in attendance and a decrease in students making Ds and Fs. One might assume that this improvement in grades would have a positive impact on retention of students. However, more research on the impact of this instructional tool is needed. If you are interested in participating with a faculty learning community devoted to trying and evaluating the effectiveness of clickers in the classroom, please consult the ECU Office for Faculty Excellence or the faculty development office on your campus.

Other student response systems

For faculty member who would like to try implementing a student response system without investing in a clicker system, there are some other options to consider, both low-tech and high-tech.

Low-tech ways of gathering student response include ideas such as individual response cards or individual white boards. While these low-tech systems do not result in electronic data, they can provide a quick look at the level of understanding within the class. When using individual response cards, each student has a set of cards from which they hold up a letter or symbol to indicate the correct response. For example, if the instructor projects or states a question prompt and three possible responses identified as A, B, or C, the students would hold up a card for A, B, or C to indicate their selection of the correct response. Likewise, when using individual white boards, students would write the letter or symbol they think represents the correct response. The anonymity afforded the student is diminished with this type of response system since students can look around the class and view others’ responses, but these systems do help with engagement and broad formative assessment.

There are student response technologies that do not require clickers but are web-based systems that use cell phones as the mode for entering responses. Among these are Poll Everywhere, SMS Poll, and Wiffiti. These systems may provide anonymity during discussions when students cannot see the responses of individual students, which is important when sensitive topics and opinions are involved. Karen Vail-Smith, an ECU instructor in Health Education, uses Wiffiti, which generates a “graffiti board” of student responses—a great tool for the sensitive topics that might be discussed in a health education class.

Educause (2011) provides a nice summary of things you should know about these types of open-ended response systems. An instructor should evaluate these cell phone-linked systems to determine accessibility, cost, and data collection. While we assume that students will always remember to bring their cell phones to class, it is important to consider the potential cost to the student for cell phone minutes and that some students may not have cell phones. The systems will not provide all the features of a clicker system, but there are features that could support some pedagogical practices in a postsecondary classroom. The cell phone and/ or wireless Internet strength in many classrooms is not sufficient to support large groups of students using mobile devices. The open-ended systems will not provide all the features of a clicker system, but there are features that could support some pedagogical practices in a postsecondary classroom.

What Students are Saying

In addition to hearing what instructors say about using clickers (student response systems) and what the research supports as the effects of using clickers, it is also important to hear from students what they perceive to be the impact of using clickers on their learning. In the spring of 2013, two East Carolina University students shared their experiences with using clickers in undergraduate classes. In the brief videos below, Fatima and Travis offer their perceptions of the potential impact of clicker use on student learning.

Summary

Students and faculty members report the following potential benefits of using clickers in the classroom. Each instructor will need to make individual decisions about potential uses and benefits in specific postsecondary classes.

Outcomes of Clicker Use For Faculty

- increased instructional time

- opportunities for real-time formative assessment

- increased student participation

- increased class energy levels

- opportunities for increased understandings about and follow-through with individual students

- decreased time spent grading

Outcomes of Clicker Use For Students

- ability to participate in class discussion – anonymously

- opportunities for immediate feedback

- practice with self-monitoring through formative assessment via class graphs

- connection with more informed instructors

- interactive classes

Remember: it is not the technology, the clicker, but the pedagogical practices for which the instructor uses the technology that make the difference in learning!

Learn More

Support is available in research literature for the use of clickers to improve classroom environments, learning, and assessment. Specifically, clickers have been linked with improvements in attendance, attention, participation, engagement, interaction, discussion, quality of learning, learning performance, feedback, and formative and summative assessment (Caldwell, 2007; Fies & Marshall, 2006; Judson & Sawada, 2002; Kay & LeSage, 2009; Mayer et al., 2009; Roschelle, Penuel, & Abrahamson, 2004; Simpson & Oliver, 2007). Although this literature supports the idea that clickers positively impact learning, some questions have arisen regarding whether the positive impact on learning is based upon the use of clickers or the pedagogical practices promoted by these tools (Bruff, 2009). For example, recent research focuses on the use of clickers to promote active-learning strategies (Deslauriers, Schelew, & Wieman, 2011; Smith et al., 2009).

Eric Mazur, a physics professor at Harvard University, uses an active learning strategy he calls “Peer Instruction,” which includes the use of clickers to increase understanding and retention of major concepts (1997). Research demonstrates that students learn more when taught with this peer-instruction model, which includes small-group activity supported by individual response (clickers), than they do with traditional lectures (Crouch & Mazur, 2001).

The video shown below titled, “Eric Mazur shows interactive teaching,” (Mazur, 2008), explains in detail why Mazur thinks active-learning strategies, such as peer instruction, help students develop deeper understanding rather than just the memorization of facts.

Additional research supports the idea that peer instruction improves student understanding and conceptual reasoning (Crouch, Watkins, Fagen, & Mazur, 2007). The following video clip titled, “The Research: Do Clickers Help Students Learn?,” (CU-SEI & CWSEI, 2009) provides examples of research at the University of Colorado that support Mazur’s work and the idea that students are learning through peer instruction.

In the examples shown in the above video clips, clickers are a tool or vehicle with which the active learning and peer interactions can be promoted and recorded.

Similarly, when considering the use of clickers in the classroom, it is essential to focus on the types and quality of questions used (Beatty, Gerace, Leonard, & Dufresne, 2006; Bruff, 2009). Creating effective clicker questions is different from creating exam questions. Bruff (2009) shares a taxonomy of clicker questions, and Beatty and colleagues (2006) suggest that clicker questions “…should have an explicit pedagogic purpose consisting of a content goal, a process goal, and a metacognitive goal” (p. 31). These authors also offer guidance about tactics to use in writing powerful questions for classroom response systems.

Extensive information about using clickers in postsecondary settings has been compiled by Derek Bruff, Director of the Center for Teaching at Vanderbilt University, including a bibliography of articles about clickers in specific content areas (Bruff, 2012). This resource, with articles grouped by content area, may be helpful for individuals who wish to see how others in their fields of study are using this technology. This information is available on the Vanderbilt Center for Teaching website (https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/clickers/).

In addition to research supporting the use of clickers in face-to-face classes, information is available about using clickers from a distance (Medina, Medina, Wanzer, Wilson, Er, & Britton, 2008) and using student response systems that do not involve clickers (EDUCAUSE, 2011), all of which may answer questions about how instructors outside of traditional lecture halls might consider using response systems.

References & Resources

Beatty, I. D., Gerace, W. J., Leonard, W. J., & Dufresne, R. J. (2006). Designing effective questions for classroom response system teaching. American Journal of Physics, 74(1), 31-39. doi:10.1119/1.2121753

Bruff, D. (2012). Classroom Response Systems (Clickers).

Bruff, D. (2009). Teaching with classroom response systems: Creating active learning environments. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Caldwell, J. E. (2007). Clickers in the large classroom: Current research and best-practice tips. CBE – Life Sciences Education, 6, 9-20. doi: 10.1187/cbe.06-12-0205

http://dx.doi.org/10.1187/cbe.06-12-0205

CAST (n.d.) About CAST: What is Universal Design for Learning. Retrieved from http://www.cast.org

CAST (2009). CAST UDL Online Modules. Retrieved from http://cast.org

Chickering, A. W., & Gamson, Z. F. (1987). Seven principles of good practice in undergraduate education. AAHE Bulletin, 39(7), 3-6.

Clark, G., Gill, N., Walker, M., & Whittle, R. (2011). Attendance and performance: Correlations and motives in lecture-based modules. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 35(2), 199-215. doi:10.1080/03098265.2010.524196

Crouch, C. H. & Mazur, E. (2001). Peer instruction: Ten years of experience and results. American Journal of Physics, 69(4), 970-977. doi: 10.1119/1.1374249

Crouch, C. H., Watkins, J., Fagen, A. P, & Mazur, E. (2007). Peer instruction: Engaging students one-on-one, all at once. (Chap. 1) In Volume 1 Research-Based Reform of University Physics. (pp. 1-55.). College Park, MD: American Association of Physics Teachers. Retrieved from http://www.compadre.org/Repository/document/ServeFile.cfm?ID=4990&DocID=241

CU-SEI & CWSEI. (2009). Clickers in the science classroom: The anatomy of a clicker question. [Video file] Retrieved from

http://www.cwsei.ubc.ca/resources/SEI_video.html or

http://www.youtube.com/watch?NR=1&feature=endscreen&v=EMhJcwvmamY

CU-SEI & CWSEI. (2009). Explaining to your students why you are using clickers. [Video file]. Retrieved from

http://www.cwsei.ubc.ca/resources/SEI_video.html or

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NGx7EzDQ-lY

CU-SEI & CWSEI. (2009). The Research. Do clickers help students learn?. [Video file]. Retrieved from

http://www.cwsei.ubc.ca/resources/SEI_video.html or

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PxKHXyVtVIA

CU-SEI & CWSEI. (2009). Students and teachers speak: Clickers in the science classroom – Why use clickers?. [Video file]. Retrieved from

http://www.cwsei.ubc.ca/resources/SEI_video.html or

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tpAEx2abKBQ&feature=channel&list=UL

Deslauriers, L.,Schelew, L. E., & Wieman, C. (2011). Improved learning in a large-enrollment physics class. Science, 332, 862-864. doi: 10.1126/science.1201783

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1201783

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/332/6031/862.full?ijkey=GMW4zTHNMM1Tc&keytype=ref&siteid=sci

EDUCAUSE. (2011). 7 things you should know about open-ended response systems.

Fies, C., & Marshall, J. (2006). Classroom response systems: A review of the literature. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 15(1), 101-109. doi: 10.1007/s10956-006-0360-1

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10956-006-0360-1

Gump, S. E. (2005). The cost of cutting class. College Teaching, 53(1), 21-26. doi:10.3200/CTCH.53.1.21-26

Guthrie, R. W. & Carlin, A. (2004). Waking the dead: Using interactive technology to engage passive listeners in the classroom. Proceedings of the Tenth Americas Conference on Information Systems, New York. Retrieved from http://www.mhhe.com/cps/docs/CPSWP_WakindDead082003.pdf

Immordino-Yang, M., & Damasio, A. (2007). We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education. Mind, Brain & Education, 1(1), 3-10. doi:10.1111/j.1751-228X.2007.00004.x

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-228X.2007.00004.x

Judson, E., & Sawada, D. (2002). Learning from past and present: Electronic response systems in college lecture halls. Journal of Computers in Mathematics and Science Teaching, 21(2), 167-181. Norfolk, VA: AACE. Retrieved from Ed/ITLib Digital Library.

Kay, R. H., & LeSage, A. (2009). Examining the benefits and challenges of using audience response systems: A review of the literature. Computers & Education, 53, 819-827. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2009.05.001

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.05.001

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/03601315/53/3

Lyubartseva, G., & Mallik, U. P. (2012). Attendance and student performance in undergraduate chemistry courses. Education, 133(1), 31-34. Retrieved from EBSCOhost.

Mayer, R. E., Stull, A., DeLeeuw, K., Almeroth, K., Bimber, B., Chun, D., . . . Zhang, H. (2009). Clickers in college classrooms: Fostering learning with questioning methods in large lecture classes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 34(1), 51-57. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2008.04.002

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2008.04.002

Mazur, E. (1997). Peer instruction: A user’s manual. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Mazur, E. [Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning]. (2008, January 20). From questions to concepts: Interactive teaching in physics [Video File]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lBYrKPoVFwg

Medina, M. S., Medina, P. J., Wanzer, D. S., Wilson, J. E., Er, N., & Britton, M. L. (2008). Use of an audience response system (ARS) in a dual-campus classroom environment. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 72(2), 38. doi:10.5688/aj720238

National Center on Universal Design for Learning. (2011). About UDL. Retrieved from http://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl

Newman-Ford, L., Fitzgibbon, K., Lloyd, S., & Thomas, S. (2008). A large-scale investigation into the relationship between attendance and attainment: A study using an innovative, electronic attendance monitoring system. Studies in Higher Education, 33(6), 699-717. doi:10.1080/03075070802457066

Reay, B. (n.d.). “Teaching with clickers.” Ohio State University. Retrieved from http://streamwww.classroom.ohio-state.edu/flash/digitalunion/12145-1

Roschelle, J., Penuel, W. R., & Abrahamson, L. (2004). Classroom response and communication systems: Research review and theory. 2004 Annual Meeting of AERA: San Diego.

Rose, D. H., Harbour, W. S., Johnston, C. S., Daley, S. G., & Abarbanell, L. (2006). Universal design for learning in postsecondary education: Reflections on principles and their application. Journal of Postsecondary Education & Disability, 19(2), 135-151. Retrieved from Education Research Complete.

Rose, D. H. & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Retrieved from http://www.cast.org/

Simpson, V., & Oliver, M. (2007). Electronic voting systems for lectures then and now: A comparison of research and practice. Australian Journal of Educational Technology, 23(2), 187-208.

Smith, M., Wood, W., Adams, W., Weiman, C., Knight, J. Guild, N., & Su, T. T. (2009). Why peer discussion improves student performance on in-call concept questions. Science, 323, 122-124. doi: 10.1126/science.1165919

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1165919

http://www.sciencemag.org/content/323/5910/122.full?ijkey=M/hcXSfjyYAas&keytype=ref&siteid=sci

UDLCAST. (2011, October 7). Introduction to UDL [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MbGkL06EU90&feature=relmfu

Additional Resources

APA Style: A DOI primer. Retrieved from http://blog.apastyle.org/apastyle/2009/09/a-doi-primer.html

Banks, D. A. (Ed.). (2006). Audience response systems in higher education: Applications and cases. Hershey, PA: Information Science Publishing. Retrieved from EBSCOhost eBook Collection database

Bruff, D. (2007). Clickers: A classroom innovation. National Education Association Advocate, 25(1), 1-8. Retrieved from http://www.hunter.cuny.edu/shp/centers/hpec/docs/clickers_and_classroom_dynamics.pdf

CAST: Center for Applied Special Technology. Retrieved from http://www.cast.org

CrossRef. (2002). DOI resolver. Retrieved from http://www.crossref.org

CU-SEI & CWSEI. (2009). Clicker resource guide: An instructors guide to the effective use of personal response systems (clickers) in teaching. Retrieved from http://www.cwsei.ubc.ca/resources/SEI_video.html

EDUCAUSE. (2005). 7 things you should know about clickers.

National Public Radio. (2012). Physicists seek to lose the lecture as a teaching tool. [Audio File].

Russell, J. How to use clickers in the classroom. [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CnnP0uCqD4k&feature=email

Science Education Initiative University of Colorado Boulder. Upper division clickers in action. [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xxigdSbL3CM

Science Education Initiative University of Colorado Boulder. Clicker and Education Videos – this site offers the videos in various formats [Video files] http://www.cwsei.ubc.ca/resources/SEI_video.html

About the Author

Subodh Dutta

Chemistry

East Carolina University

Grant Gardner

Biology

East Carolina University

Bob Green

Nursing

East Carolina University

Karen Mulcahy

Geography

East Carolina University

Janice Neil

Nursing

East Carolina University