Creative Expressions of Learning

Contents

Introduction

Creative expressions of learning facilitates a deep-level learning that grounds students in sensory awareness and fosters student engagement. In going beyond the standard triumvirate of a test, paper, and oral presentation, creative expressions enable students not only to communicate their learning but to develop a “felt sense” of it, demonstrating their knowledge in an all-encompassing way. Creative expressions of learning supplement and complement, rather than replace, traditional assignments.

While some instructors already supplement traditional practices with group projects, service-learning, Socratic dialogue, and/or experiential learning, the techniques we offer harness student creativity to express and facilitate learning. It should be noted that this practice does not teach creativity as a subject, nor does it require any level of artistic experience or background on the part of faculty or students, and can be used in multiple disciplines. This module will not show teachers how to be more creative in their presentation or lecture style, but rather how and why to design activities and assignments that require their students to be creative.

We offer here a number of techniques that can be used as assignments or projects across a variety of disciplines and can be tailored for development and use in the classroom or assigned as an out-of-class activity. Creative expressions of learning, in addition to serving as a stand-alone method of demonstrating learning, can also be a way for students to prepare for an exam, paper, or other standard assignments. In other words, students can do creative expression first, as preparation, just as they can do creative expression as the graded assignment itself.

These techniques can and should be tailored to accommodate students’ learning style differences or physical challenges as appropriate, just as the principle of UDL would dictate. With the understanding that the idea of a “creative” assignment can strike terror in the hearts of faculty and students alike, our suggestions underscore the importance of the creative process over the aesthetics of the outcome.

In describing our instructional practice and providing specific examples of the kinds of assignments that have enabled our own students to express their learning creatively, we show how these practices are beneficial to students and student learning opportunities. Later in the module, we address some challenges that instructors or their students might face when they employ these creative practices, and suggest some ways to overcome those challenges.

Objectives

After completing this module, readers will be able to:

- design content-relevant opportunities for students to use creative expression in the process of learning;

- articulate how students’ creative expression can be part of a transformational educational practice; and

- develop ways to communicate these expectations and goals to students who might find creative expressions of learning to be beyond their comfort zone.

UDL Alignment

Creative expressions help college teachers maximize inclusion of all students’ learning styles. While many instructional strategies embrace UDL by changing how the teacher presents or delivers instruction, this strategy embraces UDL by changing what we ask students to do; that is, in what we assign for students to do to express their learning and that which we grade to evaluate students’ learning.

Creative expressions of learning diverge from, but do not necessarily replace, the standard triumvirate of test taking, paper writing, and oral presentations. While paper writing and oral presentations might involve some level of creativity and student choice over the focus and style, those methods are typically designed without enabling any creative engagement with the material. Such assignments presume that all students master the material by developing standard presentations or writing standard papers on their topic. Creative expressions of learning are more personalized and affectively charged, fostering deep reflection and self-expression that connects students to what they’re learning and are designed to promote an alternative means toward mastery of material as well as to potentially serve as artifacts to assess mastery.

Acknowledging the diversity of today’s college students and enhancing access and student success is a strength of UDL. Visualization and other creative techniques expand and augment educational possibilities through using multiple modalities. Creative expressions of learning embody the following UDL principles:

Provide Multiple Means of Engagement: By offering a unique means of engagement, creative expressions of learning provide students alternatives to traditional expressions of learning as a way of acquiring and processing novel material. This helps students see the purpose of what they’re learning. In addition, students develop an authentic relationship to their learning experience, optimizing their sense of the relevance and value of their learning.

Provide Multiple Means of Representation: By offering a unique means of representation, creative expressions of learning offer novel, often non-verbal outlets of demonstrating both their knowledge and the process by which they acquired it. This enables students to apply unique and different strategies and skills for processing information, providing students a self-customizable strategy for summarizing, categorizing, contextualizing, and remembering information.

Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression: By offering a unique means of expression, students are able to integrate their own individual interpretations and responses to the material with the assignment and are likely to be motivated to go beyond the basic requirements of the assignment in demonstrating their knowledge and understanding. Since no one means of expression is best suited for all students, creative assignments allow students to find a unique way to express their learning. In addition, creative expressions of learning provide different methods–of discovery, of reflecting and processing, and of expression. Assignments that expect creative expression free students for new ways of thinking and communicating, and, as a result, new ways of learning. Furthermore, enabling students to practice a wider range of expression is well suited to our visual, media-saturated world.

Instructional Practice

Description of the Practice

Creative expressions of learning move students outside the traditional methods–exams, papers, formal oral presentations–of processing material and demonstrating knowledge. While these methods have value, so too do creative expressions of learning, which can also provide students with novel, innovative, and personal ways with which to engage academic content. Such practice-in-action methods would include, but are not limited to, the following:

- the creation of visual representations of content;

- use of multimedia technology and software;

- non-standard presentations;

- non-standard or proprioceptive writing assignments; and

- physical enactment (see examples below).

A creative expression of learning encourages the explicit connection of intellectual and emotional processing, and may include multiple, including non-verbal, modalities and methods. Providing opportunities for creative expressions of learning offers a way into course material that can lower academic anxiety for students with low academic self-efficacy and better facilitate comprehension of the material. Creative expressions provide novel ways to engage with and explore challenging material, with the goal of deep, nuanced understandings of course content. The next section provides detailed examples of this instructional practice in action. Those wanting to read more about the benefits and theory base of the practice can jump to the “Benefits of the Practice” section now and return to the “Examples of the Practice in Action” section.

Visual Representations of Content

1. Before-and-After Visual Depictions Assignment

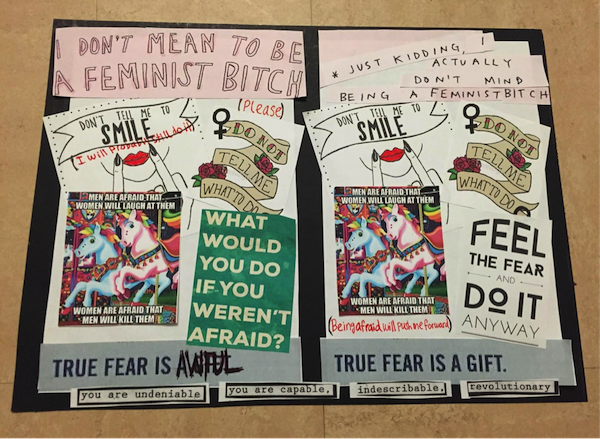

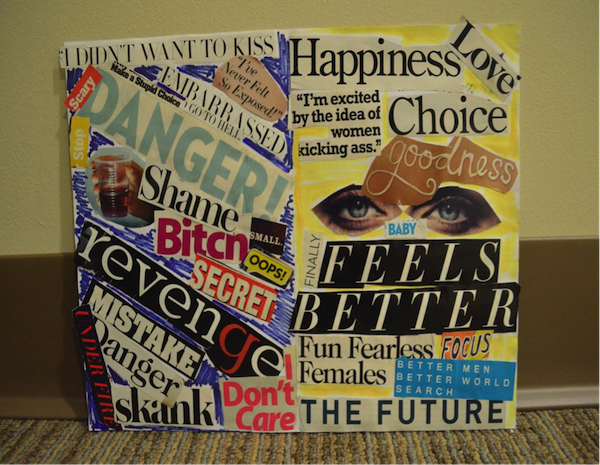

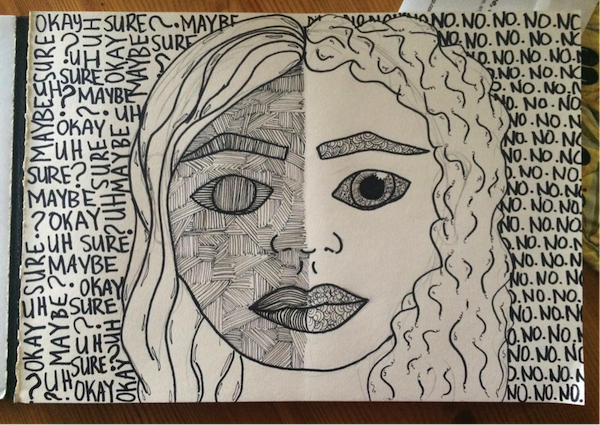

After the completion of a transformational learning experience, such as an internship, service learning course activity, study abroad trip, independent research, capstone experience, or other immersive experience, students are instructed to create a visual depiction (e.g, a collage, a drawing) of how, looking back, they saw or experienced themselves before the experience, and how they see themselves now, having completed the experience. This offers students an opportunity to use creative media to reflect on, and express visually, the impact of the learning experience on their thinking and/or self-concept. Below are three sample student products from an assignment to create a before-and-after visual narrative documenting the impact of a 20-hour self-defense training session that was an intensive part of a senior seminar on gender and violence.

Figure 1: Before-and-After student work example

Figure 2: Before-and-After student work example

Figure 3: Before-and-After student work example

Non-Standard Presentations”

1. Short-and-Sweet Presentation

In this type of presentation, students practice honing the main argument or claim of their work, communicating it simply and clearly with the audience and goal in mind. Examples of Short-and-Sweet presentations include, but are not limited to: an elevator talk, where the student enters an elevator (literally, if environment permits!), with a small group, and pitches an idea or argument in the time it takes to move between floors; tweets, where, in the spirit of LOL My Thesis, students report an argument, outcome, or summary in 140 characters or less, with an accompanying hashtag. Students create, from complex material or scholarship, slides, pamphlets, or other visual materials that would be appealing, accessible, and understandable to children. This assignment helps students pull out the most central ideas of a long, complicated document and practice communicating a central idea succinctly. As many scholars know, it can be more challenging to explain something succinctly than it is to explain it at length. Students find the idea of “short and sweet” appealing and unintimidating, even though along the way they find that the task of reporting a central idea so succinctly is challenging indeed.

2. PechaKucha™ Presentation

PechaKucha™ is a format of 20 slides at 20 seconds each, where the slides are image-based, not text-based. A presenter speaks as each carefully chosen slide conveys the point s/he is making verbally. PechaKucha™ presentations require students to select and assemble a digital collection of appropriate images that communicate a coherent message, consider issues of copyright, and practice delivering a polished, professional, live presentation. Click here to see a sample assignment description using PechaKucha™ in a first-year seminar course “Living in a Digital Age.”

Multimedia Presentation Assignment

First-Year Seminar: Living in the Digital Age

Purpose:

The purpose of this assignment is to create a creative visual presentation you give to the course in the PechaKuchaTM style, which is 20 images that show for only 20 seconds each (limiting your presentation to 400 seconds or about 6.5 minutes). Your presentation will be taking an analog-era academic article or commentary (written or spoken word story) from among the choices the professor gives you and transforming or retelling that story as a multimedia presentation. In doing so, you will gain practice assembling a stunning visual presentation appropriate for the digital age, learn about copyright and fair use of other people’s copyrighted materials, gain knowledge about the advantages and disadvantages of different communication strategies, and develop a greater understanding of the issue about which you’re presenting to the class.

Tasks to Accomplish:

___Review the format of the PechaKucha™ presentation style: http://www.pechakucha.org/presentations/how-to-create-slides

___Decide on an article or speech that you’d like to turn into a stunning visual presentation. Some examples are: “Only Connect” by William Cronon; the “new science of learning” by Todd Zakrajsek; any document or White Paper by the Electronic Frontier Foundation (e.g., “Spying on Students”); any chapter from Ken Bain’s book What the Best College Students Do; Barry Zimmerman, “Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner”; Robert Ostergard & Stacy Fisher’s “So You Thought You Knew How to Read”; JK Rowling’s TED Talk on failure; Katherine Schultz’s TED Talk called “Don’t regret Regret”; and other options the professor gives in class or that you pitch to the professor and she approves.

___Thoroughly examine the original document you are going to turn into a PechaKucha™ style presentation.

___Make your presentation in PowerPoint with a timer set, Prezi, iMovie, or another format of your choosing–so long as it follows the PechaKucha™ format.

__ Consult digital storytelling resources here if you want more ideas:

https://globaldigitalcitizen.org/64-sites-for-digital-storytelling-tools-and-information

___Choose visuals and accompanying verbal script/voice/voiceover to accurately, creatively, and effectively capture the point of the original story you are retelling in this format.

___Check/find images for your presentation that do not violate copyright law.

___Prepare to present your presentation live, where you are speaking the verbal parts of the presentation live (i.e., your voice is not prerecorded, even though it is technologically possible, of course, to set up such a presentation).

___Prepare to deliver your PechaKucha™–style presentation to classmates. Practice, practice, practice!

A Successful Assignment Will Include:

___The effective use of visual aids to accompany an oral presentation in the PechaKucha™ presentation style of 20 slides times to switch after 20 seconds each

___A written article effectively retold in an innovative new way per the above format

___A thorough explication of the original document you are presenting

___Images that are either your own creation, available in the public domain, or that constitute fair use of copyright materials

___Practiced, polished live presentation delivered to the class

___Stays within the allotted time (20 slides at 20 seconds each)

Figure 4: Multimedia Presentation Assignment example

Proprioceptive Writing

1. Letters Live Assignment

Students write a letter, informed by scholarly sources, to a person or character (real or fictional) connected with the course of study; the task is to integrate relevant scholarship on a chosen topic with the student’s own question, claim, or argument. Letters are workshopped throughout the semester to allow for revision and feedback with respect to content, organization, argument or claim, and audience. Students then read their letters in a staged reading, similar to the Letters Live Performance series, and answer questions from the audience about the content, motivation, perspective, and tone of the letter, as well as about the scholarship that informed it. This assignment enables students to articulate a claim or argument in a way that is attentive to their audience and informed by relevant scholarly sources. It also enables students to develop, and practice delivering, a polished presentation. In a required Q&A that follows their presentation, students gain practice explaining their motivation and rationale for their topic choice and letter recipient as well as the scholarship that informed their argument. In this example, students wrote and performed letters in a staged reading to a person, real or fictional, in a course on the Psychology of Harry Potter. For the assignment, students wrote and revised a 3 page, double spaced letter that had a specific, clear focus, and that dealt substantively with an important issue that they connected to the Harry Potter canon; they used one scholarly source to inform the content and claim in the letter. Below is a sample video of one student’s Letters Live performance of his letter to Professor Albus Dumbledore, a key character in the Harry Potter series, questioning the character’s claim that he was acting for the greater good.

2.Terms-of-Service Assignment

Students write a statement articulating their own stand, boundaries, or position on an issue. For example, in connection with the course materials on surveillance and privacy students make a creative terms-of-service statement on their technological decisions and boundaries in our digital age. This assignment asks students to reflect on course material and state how much privacy they want in their romantic life, their professional life, as a citizen, etc. The terms-of-service assignment could also be given to students who are learning about ethical issues in medical fields, personal boundaries in the helping professions, or a syllabus creation in education. Some students enjoy writing in this non-standard, but structured format, which encourages them to reflect on what they’ve been learning and articulate a principled, and personally relevant, position.

Use of Multi-Media Technology or Software

- Text-to-‘Toon Assignment

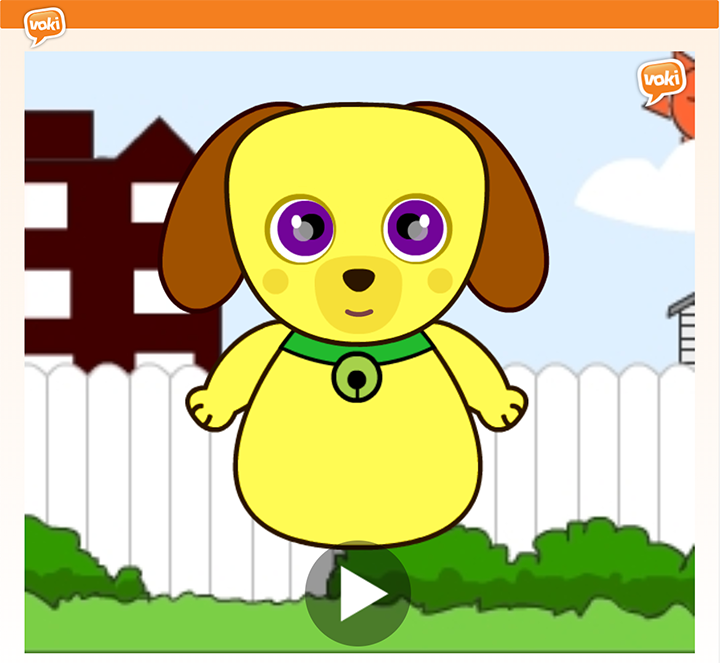

In the digital age, students are exposed to academic material via a variety of sources that go beyond the traditional textbook or hard copy of a journal article, such as learning analysis of variance by way of a YouTube video, or using grammerly.com to check or even generate appropriate grammar. This assignment creates space for students to demonstrate their own learning via a multimedia platform as a way of engaging and instructing their audience. This allows students to play with knowledge, as well as to process the content and affect associated with the material.One way of doing this is with Voki, which is a free online educational tool that allows users to create speaking cartoon characters, translating text to voice. With this technology, after reading and reflecting on the assigned material, students would write a script which they would then program their chosen Voki to deliver. This may be particularly useful in processing and demonstrating knowledge of the material that can be emotionally challenging or difficult, by allowing students to create distance from which to reflect on the content, and enable them to have “someone else” say something about a sensitive topic. For example, in a class on happiness, where students were assigned to read and explore Brene Brown’s work on shame resilience, students were asked to use Voki to make an animation that communicates the courageous things they could do for themselves when they are feeling small, hurt, or ashamed. To accomplish this, students had to write a 60-second script to demonstrate a move from shame-based to shame-resilient responding, and make a Voki cartoon as the method by which to deliver that information. Below is a sample student product from this assignment.

Figure 6: Click on image to view Voki™ video.

- Video Diary Assignment

Video diaries use smartphone apps, such as 1 Second Everyday, to piece together video clips one takes with one’s smartphone. While the most popular practice is to simply take a short video each day for a specific period of time and allow the app to string them together (30 days would be 30 seconds long), the instructional use of the video diary requires students to select a theme that will inform their daily video across a specified length of time, such as one month. Students can create one-second-a-day videos depicting a variety of topics, such as litter on campus, the work on a Christmas tree farm, or the impact of a certain health problem or political crisis. This assignment harnesses a technology students already use regularly to train their attention on a single issue being covered in the class over an extended period of time. This also enables students to find real-world examples of the topic they are studying and discussing in class. Finally, this enables students to tell a visual, rather than text-based, story of what they have been noticing. They can present and discuss their video diaries as well. The following public service announcement was created in the second-a-day format by the Save the Children Foundation to show what war does to children:

Most Shocking Second a Day Video

Physical Enactments

- Cocktail Party Activity

Similar to the game shows To Tell the Truth and Who Am I?, students are assigned a scholar (e.g., a personality theorist) or historical figure (e.g., a U.S. President) to emulate in a cocktail party setting; the task is to engage in conversation with other students about their biographical information or tenets of their theories; by the end of the “party,” students should be able to identify which student is personifying which scholar or historical figure, by applying understanding of that individual’s background and theoretical principles or notable accomplishments. By mingling about, cocktail-party style, students who play the character embody what they’ve learned while students who are charged with identifying the character actively apply their knowledge in a lively exchange. - Boundary Coaching (Role-Play) Activity

After reading and discussing theory and data on assertiveness and interpersonal boundaries, students work in teams of 3 in a role-play exercise to practice and enact the setting and maintaining of interpersonal boundaries (e.g., telling a fellow student they will not share their homework; asking a family member to call or text less frequently; addressing inappropriate behavior in a professional or social setting). Role-play scenarios can be chosen by the students, or can be suggested by the instructor and tailored to specific course content. Students take turns as the boundary violator, who role-plays the person who is behaving undesirably or inappropriately; the boundary setter, who must set and maintain the chosen boundary, and a “coach”, who can cue or make suggestions to both the individuals in the role-play to make the scenario more realistic or effective. This type of activity can be used by instructors to discuss strategies for handling interactions related to future careers, such as between teachers and parents, doctors and patients/clients, and supervisors-subordinates. Through creative enactments of chosen or assigned scenarios, students practice identifying boundaries that feel personally and professionally appropriate, formulating and practicing simple, clear, non-escalatory language to set and maintain those boundaries, and learn which strategies are more and less effective in realistic scenarios.

Benefits of the Practice

We hope that we have provided enough examples to make plain the range of ways that instructors can provide students with opportunities to express their learning creatively. Having covered what you can do and how to do it, we now turn to the why of doing it, that is, the theory base and benefits of the practice.

Visualization and other creative techniques reflect a number of UDL techniques. First, they offer an underutilized mode of reflecting on and expressing one’s learning (multiple means of expression). Second, creative methods give even those with no art training a way to make their learning authentic and relevant (multiple means of engagement). Because students are diverse, they are not all engaged by the same activity or assignment (National Center on UDL, Principle III, 2011). Providing creative ways of connecting to course material can help us reach more students. And finally, asking students to document major shifts in their thinking enables them to process and highlight big ideas through a creative medium over which they have multiple creative choices (multiple means of representation).

In aligning with UDL principles, creative expressions of learning engage students, especially those who have difficulty drafting a paper or taking an exam. Creative assignments and activities bring in the affective domain. Because students differ in how they express what they know (National Center on UDL, Principle II, 2011), creative methods can give students a variety of starting points to reflect on, capture, and express what they’re learning. Engaging students emotionally in some way helps students learn (Immordino-Yang & Damasio, 2007; Rose & Dalton, 2009).

Moreover, creative methods can also provide a method by which students can process material that is difficult, intellectually or personally, by offering a process by which students can work with and through the material in a dynamic, engaged, and interactive way.

Students making creative expressions of their learning are active participants in their learning. A creative project enables an open knowledge-making project. Creative expressions of learning can help foster intrinsic motivation in students as well as enhance learning and retention of material (Conti, Amibale, & Pollak, 1995).

Creative expressions of learning, at least during the process phase, incorporate play, enabling students to fail and try again, in relatively low-risk tasks, as a way to solve problems. This helps students learn to think creatively (Bain, 2012).

Creative expressions of learning require some degree of risk-taking, which is part and parcel of critical and creative thinking (Dorman & Brown, 2018).

High-impact practices provide structured opportunities to reflect on and integrate learning. Because some creative assignments incorporate reflecting on one’s learning, they can be harnessed to design intentional opportunities (Kuh, nd). Creative assignments ask students to do something original, exercising choice over their tasks, and while doing so reflect on and build on the materials they’ve been reading and studying in class.

Our students live in a world that requires more creativity and visual practices, which makes offering students opportunities to express and process their learning creatively all the more relevant and appropriate.

Having students approach their studies creatively can also lead to greater well-being and student engagement. The Bringing Theory to Practice (BTTP) project was founded in 2002 as a result of multiple, observable forms of disengagement among college students. BTTP has supported multiple studies of and methods to support practices that facilitate student engagement. As BTTP put it, “We are focused on the inextricable connections, in both theory and practice, among the civic, engaged learning, and well-being–the transformative conditions of flourishing, self-realization, purposefulness, and of being ‘whole’ in the world” (Pingree & Harward, 2013, p. 13).

Attention to student well-being has become a key part of a liberal education in the 21st Century. In fact, well-being came to the fore as the third case for a liberal education, after the economic case and the civic case. Educators have been working to connect well-being to the heart of the academic environment in a number of ways. Creative expression is central to well-being and thus also to the value of a liberal education, student engagement, and student success. Well-being and connectedness can be fostered through creative expressions of learning, and understood as part of the liberal education students need not only to get a better job and become responsible, civically engaged community members, but also to thrive as whole people.

Art making is a process of knowledge production (Sullivan 2003). This also places the body as something that we come to know with and through. We must create spaces where a diversity of students can give voice to feelings. Asking students to express their learning creatively sets up a pedagogical context that attends to students’ emotional lived experiences.

Creative expressions of learning, then, engage all senses and engage the whole student. In so doing, they personalize the learning and help facilitate a sense of ownership of the learning. By engaging the body, creative expressions of learning engage students more fully and help make learning transformative.

Creative expressions of learning helps teachers facilitate a connection. Students crave meaning-making, and creative expressions of learning encourage students to make that meaning. This does not mean that students are to make up whatever comes to mind, making everything ultra personal and therefore completely subjective–as if there are no facts or theories they must learn or skills they must master.

Creative expressions help foster “deep-level processing” which focuses on both substance and the underlying meaning of the information (Biggs 1989; Marton and Säljö 1976; Ramsden 2003). Deep learning integrates and synthesizes information with prior learning in ways that become part of one’s thinking and approaching new phenomena and efforts to see things from different perspectives. As Tagg (2003, 70) puts it, “deep learning is learning that takes root in our apparatus of understanding, in the embedded meanings that define us and that we use to define the world.”

Encouraging creativity that supports learner skills can help students formulate new ideas, redefine problems, solve problems in a creative manner, and apply the knowledge and skills they’re acquiring (Zimmerman, 2009, p. 382). Creative expressions of learning are not some simple self-expressions. Rather, we assign students work that harnesses their creativity to reflect on, integrate, and communicate about course-relevant ideas. It is this broader notion of creative expression that we embrace.

Finally, assigning students creative expressions of learning might become a study habit students can use in more traditional college classes that require only the basic triumvirate of exams, papers, and presentations. In other words, creative expressions of learning can become a “learning how to learn” practice or study habit if students discover that it works well for them.

Limitations of Using this Practice and Troubleshooting

Of course, it can be a challenge to consider how to integrate creative expressions of learning into academic college courses, particularly in disciplines that might see themselves as less grounded in creative or free-form expression, or in courses where faculty are concerned about imparting and assessing discipline-specific content knowledge with “correct” information that students might need for more advanced courses, future graduate or professional schools, or particular careers; the sciences come to mind as disciplines where these concerns might arise, and faculty may wonder what content to “sacrifice” in order to include creative expressions of learning.

We would argue that these concerns, while certainly understandable, reflect a misunderstanding of the purpose of creative expressions of learning, and unfamiliarity with how to tailor such assignments in a way where individual and course goals can be realized. For example, a student in an immunology course could certainly take notes on lecture material and study texts to prepare for a multiple-choice exam or to write a research paper, and we are not suggesting that such instructional and assessment methods would be inappropriate for the course. However, an assignment that utilized a creative expression of learning, such as having students role-play a scenario between a medical professional and a parent who believes vaccines cause autism, would allow students to integrate the academic research on vaccines both with the research on autism, and with research on the emotional responses of parents of children with autism and cultural beliefs about the connection between childhood vaccinations and autism. This helps students prepare for addressing misconceptions with not just data, but with compassion and empathy.

The challenges in utilizing creative expressions of learning are not limited to concerns by faculty about relevance and implementation. Students, too, may feel challenged or anxious about producing what they perceive as “art” or other creative work in the context of academic disciplines that do not “feel” artistic, or in the face of their concerns about mastery of “facts” and content. Offering students creative freedom and asking for creative expression, after years of demanding the memorization and regurgitation of information and deducting points for incorrect answers, can lead to discomfort, anxiety, and even hostility. However, it is important to note that many students will relish the opportunity to engage the course material through creative practices, and will require little to no reassurance about the importance or utility of the assignment. In an educational system where students typically work for grades and test scores, some students who do not perceive themselves as “artistic” can easily become anxious about not producing “perfect” or “A-quality work”. It is the challenge, then, of instructors to move students from a narrow focus on the outcome to a broader focus on process and reflection.

How best to address student discomfort or anxiety about creative expressions of learning? We recommend a clear explanation of why the creative expression of learning is being assigned, and a statement that their grade is not based on technical mastery or execution of artistic techniques, but on their mastery of the course material they are covering. This transparency about course goals can help ease students’ anxiety. Students, like faculty, benefit from an explanation of UDL; understanding why they are doing something is likely to increase buy-in for what we are asking them to do.

Similarly, creative expressions of learning that utilize particular technologies can be challenging for students who have no experience with or easy access to them. Therefore, some students might require brief training in the use of software that enables them to do creative work through it. For example, a student might want to do a Culture Jam assignment that would require altering a digital image and thus would need basic instructions on PhotoShop or similar software. A student might need to see a demonstration of, and practice using, Voki cartoon software or 1 Second Everyday software before embarking on the assignment. Also, some apps that have wonderful instructional uses cost money. However, free versions are often available, for instance as 30-day trials, and instructors should check with their campus learning technology support services in case their campus already holds a site license to use the desired software. Finally, it’s important to remember that many millennial and post-millennial students are probably more comfortable with new information and communication technologies, such as making memes and videos, than their instructors. However, experience with Snapchat may not translate as readily to creating a video diary with particular parameters as instructors might assume. With these issues in mind, instructors have much to offer students about using these technologies for intentional, intellectual purposes.

Paradoxically, that students have some familiarity with technology can actually interfere with their ability to use the technology to reflect on and process material. Asking students to use what they’re already comfortable using (e.g., taking videos with their smartphones, making memes, etc.) can carry the risk that students will see the fun but not the academic point. For instance, in our experience, a few students did a-second-a-day videos that simply diarized their life rather than captured an academic theme from the course. Students must be reminded that the point is not to learn how to use the technology or app per se, but to meet specific course-related learning objectives. Articulating those learning objectives clearly in the assignment instructions and providing samples of successfully completed assignments can help avoid those misunderstandings.

Of course, students will be concerned about how they will be graded on these assignments, and instructors may be concerned about how to grade them, to be sure the grade is based on understanding of the content rather than the artistry or aesthetic appeal. We suggest providing examples of successful assignments, rubrics, reassurance, and even perhaps some in-class, low-stakes opportunities for creative expression of learning. We also suggest instructors be clear about their learning goals by designing an assignment that clearly aligns with learning goals and being transparent about what knowledge and skills students are developing/practicing with this creative assignment (see Winkelmas 2013). Also, creating some restrictions can reduce anxiety around art-making. For example, instead of broad instructions like “make a collage and then write about it” students can be instructed to “find or make one picture” and “write a 3-line statement to express….” Providing structure for a creative assignment can help keep students from feeling overwhelmed by a more wide-open creative freedom in an assignment. Similarly, providing a rubric showing how the work will be graded can remind students that the focus is still on the intended skill development and content knowledge. Providing clear descriptions of assignments and rubrics that reflect the purpose and goals of the assignment can go a long way in reducing or alleviating students’ confusion or anxiety (see Fink 2013).

Learn More

Additional Considerations

We have found that students do not necessarily question the intellectual value or applicability of creative assignments, but some of our colleagues do. Colleagues who might not see the academic/instructional value of this will worry that class is all “fun and games” without academic rigor. Instructors must be clear about the specific learning objectives with which their creative activity or assignment aligns, and be prepared to show evidence of students meeting agreed upon learning outcomes. Indeed, it is important to assess students’ learning so that there is no doubt that the creative expressions of learning helped, rather than hindered, students’ meeting the learning objectives that were set for the assignment or course. In addition, instructors who assign these creative activities might do well to share the theory base framing the benefits of creative practices in learning (refer/link back to the benefits of the practice section?).

Students need to be mindful of copyright and fair use. If students are lifting copyrighted materials into their own class work they need to be reminded not to post their work publicly on social media. For example, students who make videos should share with fellow students through an internal online classroom management system such as Moodle, not on publicly accessible social media sites. Creative assignments can be a good opportunity to discuss the importance of proper citations and credits for images and multimedia sources. (See Resources listed below.)

It’s also important to assess students’ learning so that there is no doubt that the creative expressions of learning helped, rather than hindered, students’ meeting the learning objectives that were set for the assignment or course.

Resources for Learning More:

1 Second Everyday:

On copyright:

- Media Literacy Education. 2009. “Copyright Education User Rights, Section 107 Music Video” Accessed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=163&v=8tWhKeb-fUQ

For culture jam assignment inspiration:

- Hank Willis “Unbranded” exhibition https://www.blockmuseum.northwestern.edu/view/exhibitions/upcoming-exhibitions/hank-willis-thomas-unbranded.html

- Adbusters:

On how to write design significant learning experiences:

- L. Dee Fink “A Self-Directed Guide to Designing Courses for Significant Learning”:

https://www.deefinkandassociates.com/GuidetoCourseDesignAug05.pdf

For Letters Live inspiration:

LOL My Thesis: Summing Up Years of Work in One Sentence:

- http://lolmythesis.com/ Retrieved Dec. 20, 2018.

For a description of and sample PechaKucha presentations:

For the Voki video cartoon software and sample Voki cartoons:

On quick in-class, ungraded creative expressions of learning:

- McCaughey, Martha. 2016. College Star Module, “Merging Silly and Serious for Creative Expressions of Learning” Accessed at https://www.collegestar.org/modules/merging-silly-and-serious-for-creative-expressions-of-learning

On infusing writing assignments with creativity:

- Barry, Lynda. 2014. Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor. Drawn and Quarterly; Second Printing edition.

References & Resources

Bain, Ken. 2012. What the Best College Students Do. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

CAST. 2018. “Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2.” Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

CAST. 2011. Introduction to UDL. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MbGkL06EU90&feature=relmfu

Chávez, Vivian, 2009. “The Dance of Critical Pedagogy & Expressive Arts,” Newsletter of the International Expressive Arts Therapy Association, Edition No. 2, December.

Conti, Regina, Teresa M. Amibale, and Sara Pollak, 1995. “The Positive Impact of Creative Activity: Effects of Creative Task Engagement and Motivational Focus on College Students’ Learning.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 21:10 1107-1116.

Dorman, Steve, and Kelli Brown. 2018. “The Liberal Arts: Preparing the Workforce of the Future.” Liberal Education. Fall 2018, Vol. 104, No. 4. https://www.aacu.org/liberaleducation/2018/fall/dorman_brown Retrieved March 30, 2019.

Fink, D. 2013. Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ganim, Barbara, and Susan Fox. 1999. Visual Journaling: Going Deeper than Words. city, state: Quest Books.

Grammerly. https://www.grammarly.com Retrieved March 30, 2019.

Guyas, Anniina Suominen, and Kathleen Keys. 2016. “Arts-Based Educational Research as a Site for Emerging Pedagogy and Developing Mentorship,” pp. 27-43 in Mere and Easy: Collage as a Critical Practice in Pedagogy: A Collection of Articles from Visual Research, ed. by Jorge Lucero.

Kuh, George D. (n.d.) “High-Impact Educational Practices: A Brief Overview.” Association of American Colleges & Universities. https://www.aacu.org/leap/hips Retrieved March 30, 2019.

LOL My Thesis: Summing Up Years of Work in One Sentence. At http://lolmythesis.com/ Retrieved Dec. 20, 2018.

Moore, T. L. 2011. “Seeing the Client’s World Through Images and Collage.” Pp. 24-27 in Integrating the expressive arts into counseling practice: Theory-based interventions, ed. By S. Degges-White and N. L. Davis. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

National Center on Universal Design for Learning. (2011). About UDL. Retrieved from www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl

Pingree, Sally Engelhard, and Donald W. Harward, Eds. 2013. “The Well-Being and Flourishing of Students: Considering Well-being, and its Connection to Learning and Civic Engagement, as Central to the Mission of Higher Education.” Bringing Theory to Practice. https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/files/CLDE/BTtoPWellbeingInitiative.pdf Retrieved March 30, 2019.

Sullivan, G. 2003. “Seeing visual culture.” Studies in Art Education 44:3: 195-216.

Winkelmes, M. 2013. Transparency in Teaching: Faculty Share Data and Improve Students’ Learning. Liberal Education, 99(2), 48-55.

Zimmerman, Enid. 2009. “Reconceptualizing the role of creativity in art education theory and practice”, Studies in Art Education, 50:4, pp. 382–99.

About the Author

Martha McCaughy

Martha McCaughey is Professor of Sociology and recent past Director of First Year Seminar at Appalachian State University. Her courses that incorporate creative expressions of learning include a First Year Seminar on Living in the Digital Age, the Senior Seminar in sociology, and Popular Culture.

Jill Cermele

Jill Cermele is Professor of Psychology and Director of the First Year Experience at Drew University. She teaches many courses that incorporate creative expressions of learning, including Gender Violence and Women’s Resistance, Stress and Coping, the Psychology of How Not to be Miserable, and a first year seminar on the Psychology of Harry Potter.