FLIPPED CLASSROOM: Course Design to Increase Representation, Expression, and Engagement

Contents

Introduction

Flipping can take many forms, depending on the needs of the students and the instructor, but the basic concept is to push activities that a student can complete on his or her own to prepare for class (e.g. listening to a recorded lecture, watching a video, reading required materials, and/or completing an assignment) outside of classroom time. Doing so reserves in-class time for activities that engage students in the material through a variety of active learning strategies. For a brief introduction to flipping the classroom, view the 60-second summary (Schell, 2013).

This module provides an overview of the flipped classroom design, and provides detail on the many ways traditional classrooms can be flipped to provide greater student engagement. A flipped classroom reflects Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles, presenting both initial content, and opportunities for application of that content, to meet the needs of diverse learners.

Objectives

In this module, we will:

- Learn the differences between a flipped and traditional classroom

- Highlight some key barriers to implementing a flipped classroom, and how to overcome these barriers

- Discuss introducing a flipped classroom to your students, and

- Provide resources to help you design your own flipped classroom

UDL Alignment

Each College STAR module will explain how a particular instructional practice described within the module aligns with one or more of the principles of UDL. For this module, the focus will be on Provide Multiple Means of Representation, Principle I; Provide Multiple Means of Action or Expression, Principle II; and Provide Multiple Means of Engagement, Principle III.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Representation

Flipping the classroom aligns with many of the components of the UDL principle Provide Multiple Means of Representation. Since flipping is designed, in part, to make content accessible to a variety of learning types, material is typically presented in a number of formats. Use of podcasts (auditory information), video clips (auditory and visual information) and graphics (visual information) is common. Much of this information is presented via a learning management system, so students have the ability to control how they see and hear the information. Graphics can be enlarged, sound can be amplified, and key portions of videos and podcasts can be paused and re-played as needed. Additionally, a transcript for spoken content is often provided so students can read and , hear and/or see information in multiple formats. The nature of in-class work in a flipped classroom also provides many opportunities for students to generalize learning to new situations. Finally, because students follow a structured cycle when learning new information, flipped classrooms incorporate opportunities for review and practice, as well opportunities to revisit key ideas and linkages between those ideas.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression

Flipping the classroom also aligns with many of the components of the UDL principle Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression. The same digital environment that provides students with multiple means of representation also provides multiple, flexible methods for learners to devise meaning from the content of the class. In a flipped classroom, it is often advantageous to provide a guide for note-taking (e.g. guided reading questions) so that students know what to focus on as they prepare for class. Depending on the nature of the assignment or project, students in a flipped classroom have access to prompts, checklists, templates, and guides that assist with strategic planning. A large project can be broken down into manageable components, and students have the tools needed to scaffold the work.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Engagement

One of the core goals behind flipping the classroom is to increase student engagement, so this practice also aligns with the UDL principle Provide Multiple Means of Engagement. The extensive use of active learning means students work on tasks that allow for active participation and exploration. A flipped classroom also utilizes group work, which means students have ample opportunity to complete activities that foster the use of imagination to solve problems and participate in cooperative learning. Activities and tasks, both in-class and out, are varied and reflect learning outcomes that are purposeful. Learning activities also provide the opportunity for self-assessment and reflection. A flipped classroom employs a lot of variation, so instructors provide routine through a detailed schedule, and alert students to any changes in routine. Such tools help students regulate their own learning and take personal responsibility for success or failure.

Instructional Practice

The Difference between a Flipped Classroom and a Traditional Classroom

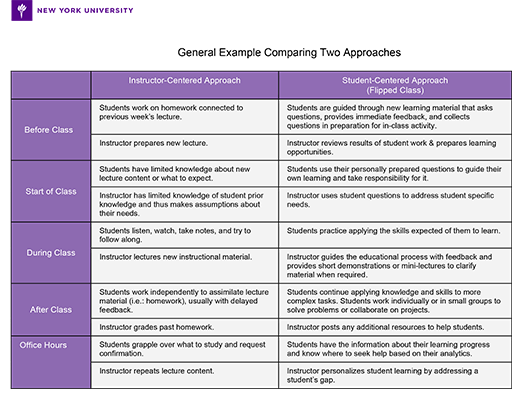

The traditional lecture-based classroom utilizes an instructor-based approach. In contrast, the flipped classroom utilizes a student-based approach (see Figure 8). Students in an instructor-centered classroom typically listen to a lecture, complete homework related to the lecture and receive feedback from the instructor, and then return to class to listen to another lecture. In a student-centered classroom, students complete activities related to the upcoming material before class time, and use class time to further apply the concepts. Use of lecture is limited. Thus, in a flipped classroom, an instructor can teach both content and process. This is important because learning occurs in two stages. In the first stage, information is transferred to the learner. In the second, the learner makes sense of the information by connecting it to his or her own experiences and organizing it (Demski, 2013). In a traditional classroom, transfer of information occurs in the classroom, and students process that information on their own. In a flipped classroom, however, the transfer of information occurs outside the classroom and students process during class.

Figure 1: Instructor vs. student-centered approach to teaching

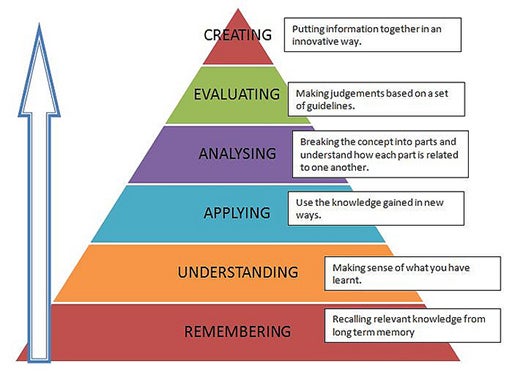

Another way to view the difference between a flipped classroom and a traditional classroom is to consider it in light of Bloom’s Taxonomy, which is depicted in Figure 9. A traditional classroom incorporates the lower-levels of the Taxonomy (Remembering, Understanding, and sometimes Applying) during class time via use of lecture, worksheets, or going through components of the textbook. Students are expected to do the top levels of the Taxonomy (Analyzing, Evaluating, and Creating) on their own. The flipped classroom reverses that structure – students work through the lower levels of the Taxonomy prior to coming to class (by reading, watching videos, and completing assignments) which reserves class time for higher-order work. By reversing the application of the taxonomy, a flipped classroom teaches students to teach themselves, which is a requirement for lifelong learning post-college (Demski, 2013; Bristol, 2014). Further, when students are expected to be significant contributors to the learning experience, it not only builds ownership, it fosters the development of leaders (Bristol, 2014).

Figure 2: Bloom’s Taxonomy

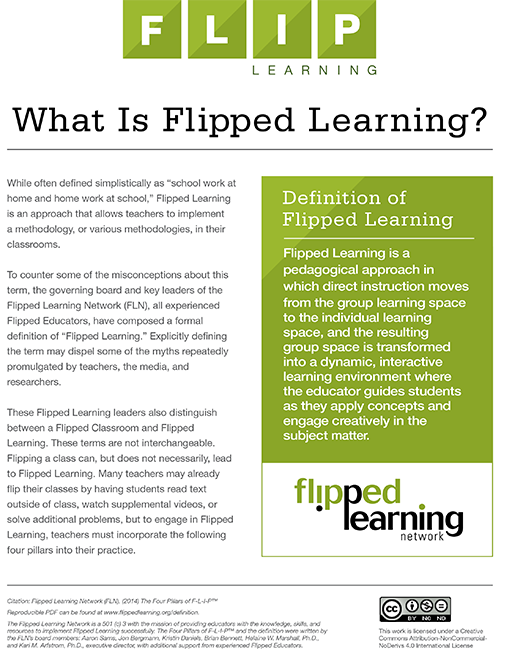

Before detailing the implementation of a flipped approach, it is important to clarify the many terms that relate to flipping. For example, there is a difference between a flipped classroom and flipped learning (Flipped Learning Network, 2014). The handout in Figure 10 details the differences. Instructors can flip a class by requiring students to read outside of class, watch videos, and/or solve problems but this may not result in flipped learning. According to the Flipped Learning Network (2014), in order for a flipped classroom to lead to flipped learning an instructor must incorporate additional practices during class time. These include providing a flexible environment (for example, by continually observing student progress and making adjustments when necessary), transitioning to a learner-centered instead of a teacher-centered culture, prioritizing content and ensuring its relevancy, and serving as a “professional educator” in the classroom by providing feedback in real-time and conducting ongoing formative assessment to inform future instruction.

Figure 3: What is flipped learning?

Other learning approaches that appear similar to flipping, because they require significant student preparation outside of class, include blended learning, team learning, just-in-time-teaching, problem-based learning, and cooperative learning (for additional detail on cooperative learning, review the College STAR Module on Cooperative Learning). Blended learning, in which students learn material via a combination of traditional classroom work and some form of web-based learning, also utilizes a video component. However, flipped learning is different because it incorporates a change in what is done during class time. The emphasis is on “students becoming the agents of their own learning rather than the object of instruction” (Hamdan, McKnight, P., McKnight, K., & Afstrom, 2013, p. 4). Team learning, developed by Larry Michaelsen, involves students being given reading assignments before class. While in class, they complete individual quizzes, group quizzes, and case studies (Michaelsen, 1992;Michaelsen, Knight, & Fink, 2002). With just-in-time teaching, students complete assignments just before class, and the instructor reviews the assignments to adjust the lesson plan. Class time is spent on material that students are struggling with (Novak, Patterson, Gavrin, & Christian, 1999). What all of these methods have in common with flipped learning is the idea that students learn best by doing, that is, by participating in active learning which is “the process of having students engage in some activity that forces them to reflect upon ideas and how they are using those ideas” (Michael, 2006, p. 7). Thus, flipped learning is certainly not the only model that facilitates good teaching. However, effective teaching may flourish more readily in flipped classrooms (Hamdan, McKnight, P., McKnight, K., & Afstrom, 2013).

Despite increased interest in, and coverage of, flipped classrooms, there are a number of misconceptions about what flipped learning actually entails. As Bergmann and colleagues (2011) note, a flipped classroom is not synonymous with online videos, or about students working in isolation or without structure. Actually, it is the learning activities and interaction with other students (and between students and the instructor) during class time that is the most important component of flipped learning. Before determining whether or not a flipped classroom makes sense for your students’ learning needs, refer to figure 11 (MathJohnson, 2012) for a succinct summary about what a flipped classroom is (and what it is not) [transcript].

Implementing a Flipped Classroom

When flipping, there is a continued focus on assessment, which can be either summative or formative. Summative assessments provide feedback on whether or not students have successfully learned what they were supposed to learn. However, such assessments are limited in terms of their ability to guide teaching because they usually occur at the endpoint of instruction (Dreon, 2014). Formative assessment, on the other hand, allows an instructor to “take the temperature” of the class, which can help guide instruction. Thus, although summative assessment is important, it is the attention to formative assessment that drives the cycle of flipped learning.

The development and implementation of a flipped classroom will depend on the specific features of the instructor, students, and material to be covered. Specific models to follow are limited. However, Bennett and colleagues (2011) provide the following list of characteristics shared by effective flipped classrooms (emphasis included):

- Discussions are led by the students where outside content is brought in and expanded.

- These discussions typically reach higher orders of critical thinking.

- Collaborative work is fluid with students shifting between various simultaneous discussions depending on their needs and interests.

- Content is given context as it relates to real-world scenarios.

- Students challenge one another during class on content.

- Student-led tutoring and collaborative learning forms spontaneously.

- Students take ownership of the material and use their knowledge to lead one another without prompting from the teacher.

- Students ask exploratory questions and have the freedom to delve beyond core curriculum.

- Students are actively engaged in problem solving and critical thinking that reaches beyond the traditional scope of the course.

- Students are transforming from passive listeners to active learners.

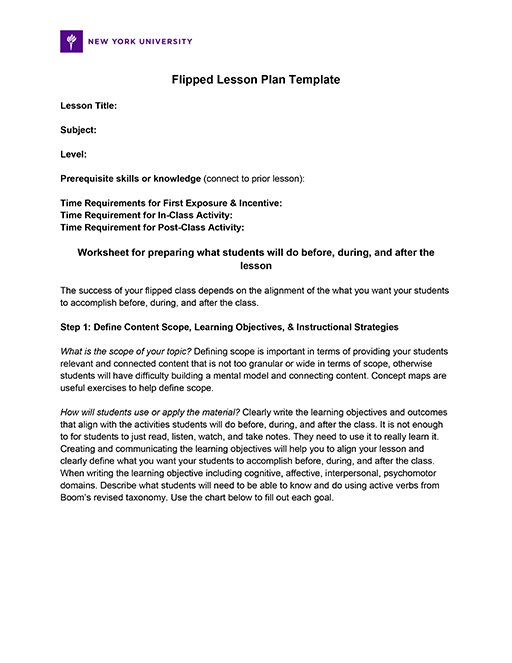

When preparing to flip a classroom, it is important to determine the essential objectives of the class, and what will constitute mastery of that objective. It is also essential, as noted in the list above, to create meaningful learning opportunities. Thus, also critical to the success of a flipped classroom is the design of the activities that students take part in before, during, and after class (many of which provide opportunities for formative assessment). The sections below detail specific examples utilized in flipped classrooms.

Introducing a Flipped Classroom

One of the key components to a successful flipped classroom is readying students for success. Introductory ice-breakers can be a way to introduce flipped classroom to students. One introductory ice-breaker is to have students form small groups to brainstorm answers to the following two questions:

- What are things professors do that make learning easy?

- What are things professors do that make learning difficult?

Inevitably, the activities that students describe that are helpful relate to a flipped learning approach while those they describe as counterproductive are related to a more traditional classroom design. Figure 12 provides some additional guidance on preparing students for a flipped classroom (Education Scribelife, 2013).

Designing and Developing Pre-Class Activities

In a flipped classroom, activities before class should assess prior knowledge (such as by having students create a concept map) or assess knowledge after students have gone through the pre-teaching material (Dreon, 2014). When it comes to reading a textbook, most college students are adept at surface-learning strategies that were learned in high school. However, they are generally unprepared for college-level reading which requires engagement and analysis (and is a skill that is generally not taught at any level of education) (Weimer, 2010). Instructors often use quizzes to ensure students read before coming to class, but Roberts and Roberts (2008) are critical of using quizzes in this manner because it focuses on surface learning and encourages short-term memorization as opposed to long-term comprehension. Rather, they require students to create a reading response for 25 of the 29 required readings. Responses could take one of the five following forms:

- Drafting five “big” questions on key concepts in the chapter, and either answering two or writing a commentary on why they think these are the core issues of the reading.

- Making a visual or graphic organizer for content in the reading, or a chart or list that organizes and categorizes ideas.

- Completing a reading response journal.

- Convening as a study group and recording and writing up the ideas discussed.

- Creating a song or rap about the assignment.

Additional activities designed to ensure students read before coming to class include encouraging use of supplemental material provided with the textbook (and demonstrating to students where it is and how to use it) and having students submit answers to three to five questions about the reading prior to coming to class (Coffman, 2010).

SAMPLE PRE-CLASS ASSIGNMENT FOR POLICING & SOCIETY

The seniority system means that rookie officers will generally be assigned to patrol in the highest-crime neighborhoods during the busiest shift (e.g. 4:00 pm to midnight) when most of the serious crime occurs. Consider the following questions:

- Is this a good system for assigning officers? Does it result in the best police service to those times and places that demand the most skill?

- What are the major drawbacks to this system? What are the advantages? Can you develop an alternative system? What would it look like?

Designing Your Own Flipped Classroom

Transitioning from a traditional classroom to a flipped classroom can provide many benefits to both the student and the instructor, but it takes time and thoughtful planning. Figure 13 (GoEd Online, 2012) provides some tips from John Sowash, an experienced “flipper.”

Demski (2013) interviewed a number of instructors considered to be experts at flipping, and they offered the following tips:

- A seemingly chaotic classroom is okay – students are actively engaging in the material and that is nosier than a classroom in which students are passively listening

- Make use of existing technology – a lot of lecture capture technologies provide features that support flipped learning (and, further, many are already integrated into the learning management system for a college or university making it easy for both faculty and students to navigate)

- Expect that it will take time to get students on board. According to Robert Talbert, who has flipped his mathematics course, “students come in with a specific mental model of how a classroom out to work that is quite ingrained . . . When you invert the situation and make them active participants, it really takes a long time, a lot of repetition, and a lot of marketing to get students to buy into this” (p. 2).

- Let students learn from one another. When a well-intentioned instructor inserts him or herself into the learning process, it usually stifles student discussion.

- Use pre-class assignments to assess student understanding to make the best use of class time.

- Set a specific target and identify particular units where students can really benefit from the model.

- Build assessments that complement the flipped model, but understand that “the prevalence of teamwork in a flipped classroom presents an assessment challenge” (p. 3).

Overcoming Barriers to Success in a Flipped Classroom

Although a flipped classroom can be a rewarding experience for both the instructor and the students, there are some recognized challenges that can hamper success implementation. For example, the time and effort needed to redesign a course from a traditional format to a flipped format can be daunting (Yarbro, Afstrom, McKnight, K., & McKnight, P., 2014; Aronson, Afstrom, & Tam, 2013). One instructor estimated that developing and administering his flipped course took 127% more time than teaching in the traditional format (McLaughlin et al, 2014). To help overcome this challenge, instructors seeking to implement a flipped classroom for the first time could work as a team. Further, it is important for departments and universities to ensure that instructors and professors are trained in how to infuse flipped learning into their classes (Aronson, Afstrom, & Tam, 2013).

Another potential challenge is students not coming prepared to class. This can be a serious barrier as “the foundation of flipping the classroom is a student that arrives to class ready for the learning experience” (Bristol, 2014, p. 3). For the typical college student, this is somewhat ingrained behavior as students are often not penalized for coming unprepared to a traditional classroom. Many have little incentive to read prior to class because they know the instructor will cover all the necessary content in the lecture. One way to overcome this barrier is to utilize “guided study.” Students need to perform activities (and be held accountable for performing those activities) prior to class that demonstrate understanding of the concepts to be explored during class. An additional consideration with this challenge is that students tend to have very little understanding of time and task management, which is an essential skill in a flipped course.

A final challenge is student resistance to the flipped classroom. When an instructor uses active learning strategies, students are required to put in more effort during class, and to stay on pace with the rate of instruction. Most students will resist learning at the rate that class is going in favor of letting things slide and cramming at the last moment (Aronson, Afstrom, & Tam, 2013). As noted previously, one way to solve this problem is by requiring students to take a quiz or complete homework that references information that is only contained in the material (Herreid & Schiller, 2013).

Learn More

Literature Base

As mentioned, a flipped classroom differs from a traditional classroom in a number of key ways, but most notably in the structure of before-class and in-class work. The pioneers of the flipped classroom, Jonathan Bergmann and Aaron Sams, began to use live video recordings and screencasting software in 2007 to accommodate students who frequently missed end-of-day classes to travel to other schools for competition. Although it was not their intent when they changed the delivery of class material, Bergmann and Sams also discovered that students began interacting more in class once they started viewing the videos (Hamdan, McKnight, P., McKnight, K., & Afstrom, 2013).

Despite some potential barriers to successful implementation, such as the additional time needed to design and develop a flipped classroom and student resistance to the new format, Fulton (2012) notes that a flipped classroom offers a number of advantages. These include:

- Students move at their own pace.

- In-class activities give teachers better insight into student difficulties and learning styles.

- Teachers can more easily update and customize the curriculum.

- Classroom time can be used more effectively and creatively.

- Student achievement, interest, and engagement is increased.

- Use of technology is flexible and appropriate for 21st century learning.

The Flipped Learning Network (Hamdan, McKnight, P., McKnight, K., & Afstrom, 2013; Yarbro, Afstrom, McKnight, K., & McKnight, P., 2014) has compiled two literature reviews that assess the state of research on flipped learning. To date, there has been relatively little empirical research on flipped learning, and the research that has been done has been largely non-experimental. However, the research that has been done indicates that students in a flipped course students’ progress through material faster and understand topics in greater depth (Papadopoulos & Roman, 2010). Further, the flipped learning model may positively impact student performance in subsequent courses within a major (Ruddick, 2012).

Some findings also indicate that a flipped classroom and flipped learning improves student performance. For example, an introductory biology class at the University of Washington, Seattle had a 17% failure rate. After the instructor adopted flipped learning, the failure rate decreased to 4% (Aronson, Afstron, & Tam, 2013). At the University of British Columbia, two instructors experimented with their respective sections of a physics course. During the last week of the semester, one section retained its traditional format while the other went to a flipped format. In the flipped course, student attendance increased by 20%, and student engagement increased by 40%. Further, students in the flipped course scored more than twice as well on a multiple choice exam measuring content in the final week as students in the control group (Aronson, Afstron, & Tam, 2013). Flipping can also improve student performance at the graduate level. Students who participated in a flipped pharmaceutical course had significantly better final exam scores than graduate students in a traditional format of the same course (McLaughlin et al, 2014). Additionally, research on active learning has shown that such strategies improve academic performance (Knight & Wood, 2005; Michael, 2006; Freeman et al., 2007) and increase student engagement (O’Dowd & Aguilar-Roca, 2009). Marshall and DeCapua (2013) also note that a flipped classroom can help learners that are struggling because it allows them more opportunities to review and understand material before class.

Other researchers, however, have reported null or negative findings. Frederickson and colleagues (2005) found no significant differences in students’ knowledge between two versions of a research methods and statistics course while Strayer (2012) reported that students in introductory statistics were less satisfied with the way they were prepared for the tasks they were given. However, those same students also reported that they were more open to cooperative learning. Since research to date is rather limited, and the findings reported are mixed, future research should consider under what conditions flipped learning can be most effective (Lape et al, 2014).

References & Resources

Alvarez, B. (2012). FLIPPING THE CLASSROOM: Homework in class, lessons at home. Education Digest, 77(8), 18-21. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=83515506&site=ehost-live

APA style: A DOI primer.http://blog.apastyle.org/apastyle/2009/09/a-doi-primer.html

Aronson, N., Afstrom, K. M., & Tam, K. (2013). Flipped learning in higher education Pearson.

Baker, L. M., & Settle, Q. (2013). Flipping the classroom and furthering our careers. NACTA Journal,57(3), 75-75. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=93664261&site=ehost-live

Bennett, B., Kern, J., & Gudenrath, A. M.,Philip. (June 23, 2011, The flipped class: What does a good one look like? The Daily Riff,

Bergmann, J., Overmyer, J., & Willie, B. (July 21, 2011), The flipped class: What it is and what is it not. The Daily Riff,

Bergmann, J. (2014). The flipped learning network.www.flippedlearning.org

Bergmann, J., & Sams, A. (2013). Flipping for mastery. Educational Leadership, 71(4), 24-29. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=92606745&site=ehost-live

Berrett, D. (2012). How “flipping” the classroom can improve the traditional lecture. Education Digest: Essential Readings Condensed for Quick Review, 78(1), 36-41. Retrieved fromhttp://chronicle.com/article/How-Flipping-the-Classroom/130857/

Bristol, T. (2014). Flipping the classroom. Teaching & Learning in Nursing, 9(1), 43-46. doi:10.1016/j.teln.2013.11.002

Brunsell, E., & Horejsi, M. (2013). Flipping your classroom in one “take”. Science Teacher, 80(3), 8-8. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE|A323260080&v=2.1&u=4104mtnla&it=r&inPS=true&prodId=PROF&userGroupName=4104mtnla&p=PROF&digest=9a0f11b7adb71006c47458339479d277&rssr=rss

CAST (n.d.) About CAST: What is Universal Design for Learning. Retrieved from http://www.cast.org

CAST (2009). CAST UDL Online Modules. Retrieved from http://www.cast.org

Coffman, S. J. (July 2010). How to get students to read what’s assigned. In M. Weimer (Ed.), 11 strategies for getting students to read what’s assigned (pp. 15). Madison, WI: Magna Publications, Inc.

Covill, D., Patel, B. A., & Gill, D. S. (2013). Flipping the classroom to support learning: An overview of flipped classes from science, engineering and product design. School Science Review,95(350), 73-80. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=90262461&site=ehost-live

Demski, J. (2013). 6 expert tips for flipping the classroom. Campus Technology, 25(5), 32-37. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ1006565&site=ehost-live; http://campustechnology.com/research/2013/01/magazine_january.aspx?tc=page0

Dreon, O. (July 23, 2014), Formative assessment: The secret sauce of blended success. Faculty Focus,

Preparing students for a flipped classroom. Education Scribelife (Director). (January 4, 2013).[Video/DVD]

EnACT. (n.d.) 14 common elements of UDL in the college classroom.

Evans, C., Williams, J. B., King, L., & Metcalf, D. (2010). Modeling, guided instruction, and application of UDL in a rural special education teacher preparation program. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 29(4), 41-48.

Retrieved from Education Research Complete

Faculty Focus. (July 2010). In Weimer M. (Ed.), 11 strategies for getting students to read what’s assigned. Madison, WI: Magna Publications, Inc.

Faculty Focus. (July 2014). In Bart M. (Ed.), Blended and flipped: Exploring new models for effective teaching and learning. Madison, WI: Magna Publications, Inc.

Ferreri, S. P., & O’Connor, S. K. (2013). Redesign of a large lecture course into a small-group learning course. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 77(1), 1.

Finkel, E. (2012). Flipping the script in K12. District Administration, 48(10), 28-30.

Flipped Learning Network. (2014). The four pillars of F-L-I-P™

The four steps of flipping.(2014). Tech & Learning, 34(9), 10-10.

Frederickson, N., Reed, P., & Clifford, V. (2005). Evaluating web-supported learning versus lecture-based learning: Quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Kluwer Academic Publishers,50(4), 645-664.

Freeman, S., O’Connor, E., Parks, J. W., Cunningham, M., Hurley, D., Haak, D., et al. (2007). Prescribed active learning increases performance in introductory biology. CBE Life Science Education, 6, 132-139.

Fulton, K. (2012). Upside down and inside out: Flip your classroom to improve student learning. Learning & Leading with Technology, 39(8), 12-17. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=eric&AN=EJ982840&site=ehost-live

Garver, M. S., & Roberts, B. A. (2013). Flipping & clicking your way to higher-order learning.Marketing Education Review, 23(1), 17-22. doi:10.2753/MER1052-8008230103

Gerstein, J. (2011). The flipped classroom model: A full picture

Hamdan, N., McKnight, P. E., McKnight, K., & Afstrom, K. M. (2013). A review of flipped learning The Flipped Learning Network.

Herreid, C. F., & Schiller, N. A. (2013). Case studies and the flipped classroom. Journal of College Science Teaching, 42(5), 62.

Immordino-Yang, M., & Damasio, A. (2007). We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education, Mind, Brain & Education, 1(1), 3-10. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-228X.2007.00004.x

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-228X.2007.00004.x

International DOI Foundation. (2012). Resolve a doi number.http://www.doi.org

Jaster, R. W. (2013). Flipping college algebra: Perceptions, engagement, and grade outcomes. MathAMATYC Educator, 5(1), 16-22. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=90557243&site=ehost-live

Keene, K. (2013). Blending and flipping distance education. Distance Learning, 10(4), 63-69. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=93996535&site=ehost-live

Knight, J. K., & Wood, W. B. (2005). Teaching more by lecturing less. Cell Biology Education, 4, 298-310.

Kundart, J. (2012). Khan academy and “flipping the classroom.”. Optometric Education, 37(3), 104-106. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=78202069&site=ehost-live

Lape, N., Levy, R., & Yong, D. (April 25, 2014, Can flipped classrooms help students learn? we are trying to find out. Slate,

Maloy, R. W., Edwards, S. A., & Evans, A. (2014). Wikis, workshops and writing: Strategies for flipping a college community engagement course. Journal of Educators Online, 11(1), 1-23. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=95003330&site=ehost-live

Marshall, H. W., & DeCapua, A. (2013). Making the transition to classroom success: Culturally responsive teaching for struggling language learners. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press/ELT.

MathJohnson (Director). (May 7, 2012).[Video/DVD]

McLaughlin, J. C. (2014). The flipped classroom: A course redesign to foster learning and engagement in a health professions school. Academic Medicine, 89, 1-8.

Michael, J. (2006). Where’s the evidence that active learning works? Advances in Physiology Education, 30, 159-167.

Michaelsen, L. K. (1992). Team learning: A comprehensive approach for harnessing the power of small groups in higher education. To Improve the Academy, 11, 107-122.

Michaelsen, L. K., Knight, A., & Fink, L. D. (2002). Team-based learning: A transformative use of small groups. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Missildine, K., Fountain, R., Summers, L., & Gosselin, K. (2013). Flipping the classroom to improve student performance and satisfaction. Journal of Nursing Education, 52(10), 597-599. doi:10.3928/01484834-20130919-03

National Center on Universal Design for Learning. (2011). About UDL. Retrieved fromhttp://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl

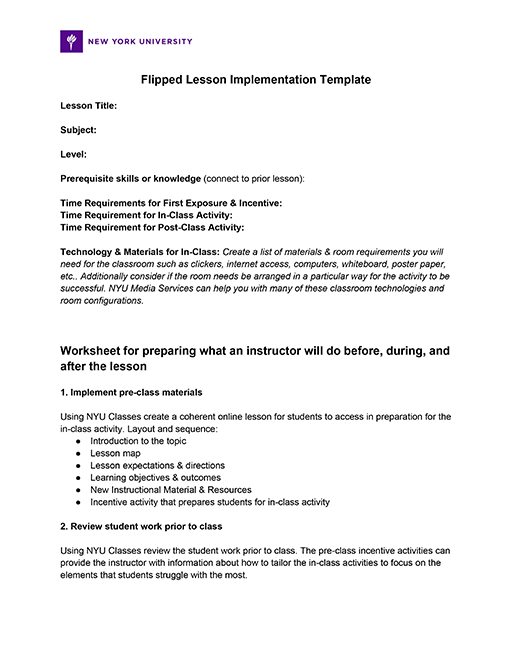

New York University. (2014). Steps to flipping your class.

Novak, G. M., Patterson, E. T., Gavrin, A. D., & Christian, W. (1999). Just-in-time teaching: Blending active learning with web technology. New York, NY: Prentice Hall.

O’Dowd, D. K., & Aguilar-Roca, N. (2009). CBE Life Science Education, 8, 118-122.

Papadapoulos, C., & Roman, A. S. (2010). Implementing and inverted classroom model in engineering statistics: Initial results. Proceedings of the 40th ASEE/IEE Frontiers in Education Conference, Washington, DC.

Roberts, J. C., & Roberts, K. A. (2008). Deep reading, cost/benefit, and the construction of meaning: Enhancing reading comprehension and deep learning in sociology courses. Teaching Sociology, 36, 125-140.

Rose, D., & Dalton, B. (2009). Learning to read in the digital age. Mind, Brain & Education, 3(2), 74-83. doi:10.1111/j.1751-228X.2009.01057.x

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-228X.2009.01057.x

Rose, D. H., Harbour, W. S., Johnston, C. S., Daley, S. G., & Abarbanell, L. (2006). Universal design for learning in postsecondary education: Reflections on principles and their application.Journal of Postsecondary Education & Disability, 19(2), 135-151.

Retrieved from Education Research Complete.

Rose, D. H. & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum.

Retrieved from http://www.cast.org

Ruddick, K. W. (2012). Improving chemical education from high school to college using a more hands-on approach. Unpublished Retrieved from ProQuest Digital Dissertations.

What is the flipped classroom? (in 60 seconds). Schell, J. (Director). (April 22, 2013).[Video/DVD]

Schwartz, T. A. (2014). Flipping the statistics classroom in nursing education. Journal of Nursing Education, 53(4), 199-206. doi:10.3928/0148434-20140325-02

Simonson, S. R. (2014). Making students do the thinking: Team-based learning in a laboratory course.Advances in Physiology Education, 38(1), 49-55. doi:10.1152/advan.00108.2013

Smith, J. (2013). Flipping to address all learners. Business Education Forum, 68(2), 35-38. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=95214384&site=ehost-live

Spencer, D., Wolf, D., & Sams, A. (June 22, 2011, Are you ready to flip? The Daily Riff,

Steffen, B. (2013). Flipping my teaching. Educational Leadership, 70(6), 92-92. Retrieved fromhttp://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=85833643&site=ehost-live

Strayer, J. F. (2012). How learning in an inverted classroom influences cooperation, innovation and task orientation. Learning Environments Research, 15(2), 171-193. doi:10.1007/s10984-012-9108-4

The Flipped Institute. (2014). The flipped institute.www.flippedinstitute.org

UDLCAST. (2011, October 7). Introduction to UDL [Video file]. Retrieved fromhttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MbGkL06EU90&feature=relmfu

Vaughan, M. (2014). Flipping the learning: An investigation into the use of the flipped classroom model in an introductory teaching course. Education Research & Perspectives, 41(1), 25-41. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ehh&AN=96304324&site=ehost-live

Weimer, M. (July 2010). Still more on developing reading skills. In M. Weimer (Ed.), 11 strategies for getting students to read what’s assigned (pp. 8). Madison, WI: Magna Publications, Inc.

Yarbro, J., Arfstrom, K. M., McKnight, K., & McKnight, P. E. (2014). Extension of a review of flipped learning Pearson.

About the Author

Heidi Bonner

Criminal Justice

East Carolina University