Flipping so as not to Flop: The Blended Classroom

Contents

Introduction

Multiple studies have shown that active classroom engagement and critical thinking/problem solving skills can lead to enhanced student learning, as measured by increased grades, student engagement, and reductions in content misconceptions [1]. In a “flipped classroom”, the lecture and homework components of a traditional class session are reversed. Students read or listen to content at home while completing activities in student groups during the scheduled class periods. This works well in smaller classrooms where groups can easily be formed and managed. However, in many STEM disciplines, the traditional lecture is used in a large lecture class [2], as this format can provide core content to hundreds of students at once with only one professor, and economical to a professor’s time, with one PowerPoint/lecture needed. In addition, as many large lecture halls have immoveable seating, group work is not feasible. Finally, students are often resistant to this type of change, stating that they want the traditional lectures and not active, group work during class time [3]. Blending learning describes an educational model where classroom time in a lecture format is combined with online learning, and in-class group activities [4]. This video give a good overview of blended learning:

The blended classroom format usually uses smaller classrooms, but can be modified to allow for professors with large classes to use it, as we will see in this module. The key, in my opinion, is making sure that engagement with the online material is tracked or tested for, both online, and in class. This module will describe the experience of using a blended model for increasing active learning in ~250-student nutrition course, while still providing lectures and pre-class video and reading materials. The professor will discuss her experiences with using a blended classroom, provide student feedback on the course, and provide example course materials and methods to help others test this format in their courses.

Objectives

This module offers instructors:

- A set of concrete examples for using the blended classroom format in a large lecture-type course.

- A discussion of pros and cons of the different technologies used in the blended classroom.

- Examples of student feedback about course design and critical thinking gains obtained during a sample blended course.

UDL Alignment

Each College STAR module will explain how a particular instructional practice described within the module aligns with one or more of the principles of UDL. For this module, all three of the UDL principles will be addressed:

Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Representation

Multiple formats for providing information in class, in homework, and in exams are provided.

Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Action or Expression

Multiple tools, including lecture capture, pre-lecture videos, text, in-class lectures, pre-class readings are illustrated.

Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Engagement

Group work and in-class lectures are used in the course depicted in this case study, as well as individualized question/answer formats.

Instructional Practice

The Course

The course that will be discussed in this case study is a course on Metabolic Nutrition, specifically the biochemistry of vitamins and minerals. The class meets on a Tuesday/Thursday schedule with 1 hour, 15 minutes per class, and is taught at the 4000 level (upper level undergraduates). The course is taught in a traditional large lecture hall, with immoveable stadium seating.

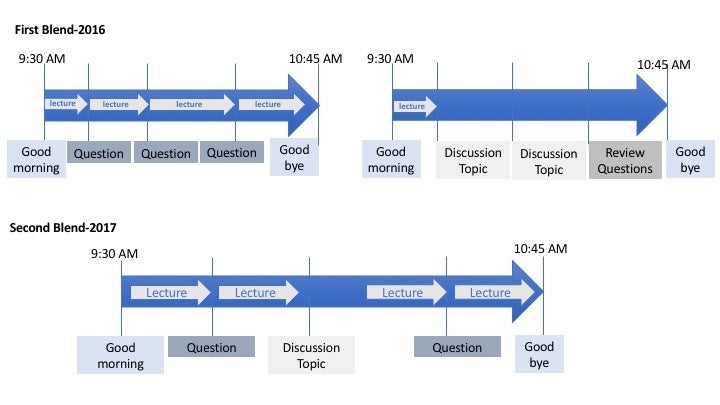

Over a period of two semesters, I tested two different formats of a blended classroom approach (Figure 1). In the first semester, students were provided with online material to prepare for a once per week traditional lecture, and then they applied their knowledge during group activities during the second class period of the week. During the second semester, online material was posted for students to prepare for the week, and the formal lectures on both days were broken into question-answer periods, and analysis work. Students could choose to work alone or in groups. All classes, both semesters were 75 minutes long, twice per week.

Figure 1: Two different formats of a semester-long, blended classroom, approach.

The Tools

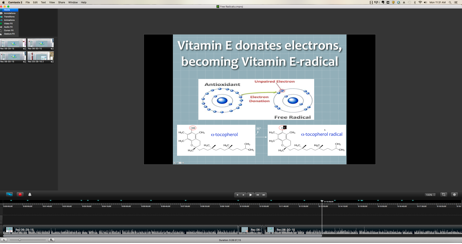

Video recording tools: Students had access to online videos and asked to view them prior to the start of each week. The videos were no longer than 15 minutes, and usually students only had one or two videos to view prior to class. Videos were recorded using PowerPoint presentations and Camtasia™ (Techsmith) video (Figure 2). Other tools such as Echo360 (in class lecture capture) or Jing (free, smaller version of Camtasia) could also be used.

Figure 2: Example screen shot of Camtasia™ video software. The timeline runs along the bottom, and once a presentation is recorded, the user can do multiple types of cropping, highlighting and editing.

The textbook: The instructor authored a textbook [5] in which assigned readings were given each week. Students were tested on readings as well as in class work, and pre-class videos.

In-class Response systems: TopHat™ (Tophat.com) in class response systems were used for both semesters of the course, but in slightly different ways, which will be discussed. Other in-class response systems include iClicker, Poll Anywhere, and Lecture Tools (part of Echo360).

Course/Learning management platform: Our university currently uses Canvas, but other platforms such as Google classroom and Blackboard could substitute.

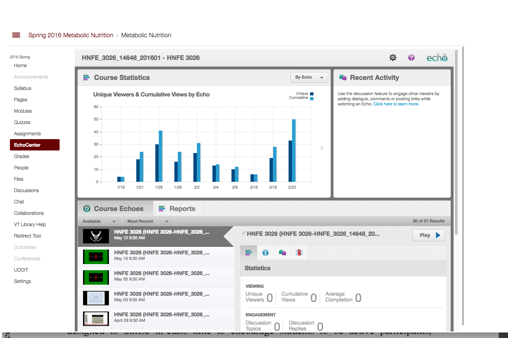

Lecture Capture: The classroom was equipped with Echo360 Lecture capture technology. Lectures were broadcast synchronously, and could be viewed live, or recorded by students. The Echo360 software integrates into the Canvas learning management platform, as shown in Figure 3, which allows the professor to see how many people are viewing the recorded lectures.

Figure 3: Example screen shot of course statistics for Echo360 Live Classroom Lecture Capture. Each date can be selected to see how many students accessed the live versus captured video. One can also see a histogram (not shown) of individual regions of the video that were viewed (re-viewed) most often.

First Blend

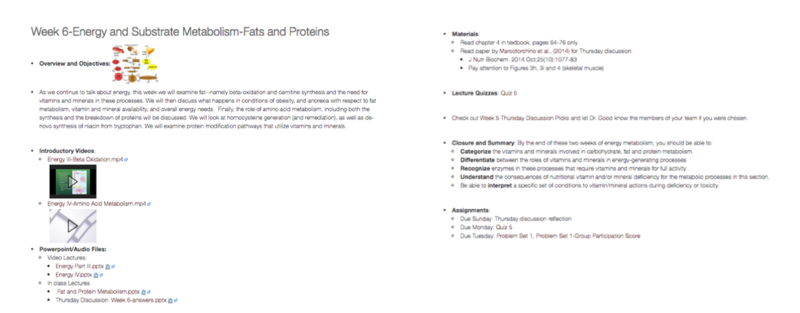

In this iteration, 226 students were enrolled in the course, and the class was supported by two full-time graduate teaching assistants (GTAs) and five undergraduate teaching assistants (UTAs). The UTAs received a two-credit hour independent study, and all had taken the Metabolic Nutrition course during the previous semester. A one-hour meeting was held each week between the TAs and the professor to discuss the upcoming group activities and review the outcomes and pitfalls from the previous week. The TAs helped design and discuss the active learning materials for the group activities and moderate student groups during the in-class activities. All of the course material was put on a canvas website in module format (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Example screen shot of Canvas Website for a blended class. As you can see, there is a combination of introductory videos to watch (along with the accompanying PowerPoint file for the video lecture), in class lecture material, and material to read (both textbook and papers).

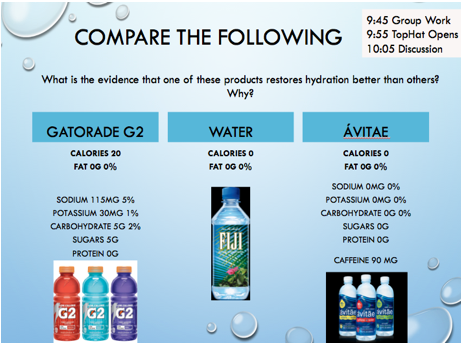

Students in the course were given pre-class videos assigned to be watched prior to the first lecture period of the week. Lectures with some interactive questions via TopHat™ were held on Tuesdays during the 75 minute class period. On Thursdays, only brief introductory information was given, and students were given group activities. The group activity started with an open-ended question where students researched their answer using a credible medical website (i.e. PubMed, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, Food and Nutrition Board). The question was such that the answer was not directly covered in any course material (lecture or online), but rather expanded on their past knowledge in the previous lecture. In some cases (see figure), different groups had different topics to investigate (Figure 5). Approximately 10 minutes was given for groups to complete the research and then post to the TopHat™ Discussion boards. Then, an additional 10 minutes were used to discuss findings, and students volunteered to present to the class. The professor then summarized the findings. Each Thursday students had one or two of these group activity questions to complete. The rest of the class period was devoted to open-ended review questions from the material for the week. Students answered using TopHat™ and received extra credit points for the fastest and most complete answers.

Figure 5: Example screen shot of a PowerPoint prompt for group work used during class. The timing for the group work is laid out for the students, and students already know which section of the classroom they are in, and thus, which type of hydration product (in this case) to investigate.

At the end of each week, students were required to write a weekly reflection that further expanded the Thursday discussion material by having them search a little more or expand in a different direction individually. Exams contained both multiple choice questions, and open-ended essay questions similar to the in-class activities. Problem sets were spaced throughout the semester. Students were also graded on attendance, taken at the beginning of class using TopHat™ software.

Student comments on format

Surveys were done at the end of the course (in addition to the regular university “Student Perception of Teaching” SPOT surveys). Free responses were coded by two individuals as to whether blended class format or lecture format was preferred, or if the comment was neutral about the two types. While 36.6% of the students preferred lectures, 46.6% of the class made comments that indicated that they preferred the blended class format. Another 16.8% of students left neutral comments. Examples include the following:

“Overall, I liked the blended class structure – it made the class a little more entertaining than having to spend an hour and 15 minutes listening to lectures every class“

“I am used to a standard lecture-style, and I believe my learning style thrives more in that setting”

“I also thought the Thursday discussion was pretty interesting. I enjoyed being able to work with other people in the class and understand their ideas and prospective, while incorporating it into what we were doing that week in the class”

“I also thought the Thursday discussions were not very stimulating and I found myself not really caring about what was being discussed because, in my mind, it had no importance to what we would be tested on”

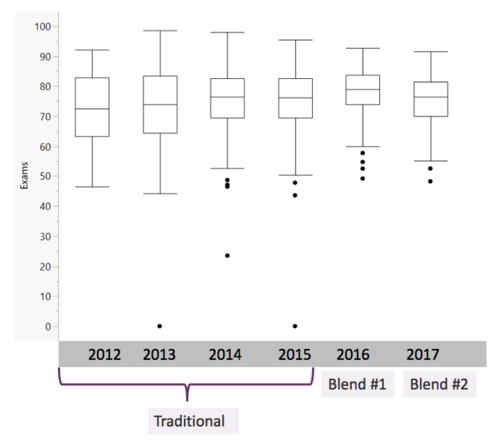

Interestingly, analysis of course grades over the last four years indicates that both overall course grades and exam grades improved with the blended format, as compared to lecture only. In addition, the standard deviation for the scores were narrowed, suggesting that grades for students from the bottom and middle portion of the grading scale were being brought up (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Histogram plots of average grade on exams Average exam grades for all Metabolic Nutrition course taught by Dr. Good from 2012-2017. Outliers are shown as dots. The data are shown as mean percents ± SD. * P ≥ 0.05 compared to 2016 data; ** P ≥ 0.01, compared to 2016 data. Statistical comparison of 2017 data has not yet been done.

Second Blend

Based on the comments made by students suggesting that many (36.6%) felt that they preferred an “all lecture” course, but also considering the improvement in grades that occurred with blending, a modification of the blended model used in 2016 was used in the spring 2017 course. In this modification, both Tuesday and Thursday modules had discussions, questions, and lecture times. Review questions were left to a single day prior to the exam. Analysis of the exam scores showed that there was still a reduction in variance, and fewer outliers using this new format (Figure 7).

In this second year of the blended course, we analyzed self-reported critical thinking skills in a pre- and post- format, and are currently determining if there are any improvements in critical thinking for students taking the course. Student comments from the survey included:

“My skills at critical thinking and reading/interpreting scientific literature have largely increased due to this class!”

“I did enjoy the format of this course, and I do truly think that it encouraged more reading and thinking than many biology oriented classes I have taken in the past.”

“I believe my skills to interpret scientific literature was improved by being in this class. I also find myself engaging in more critical thinking in both school and every day life after taking (this course).”

“I believe that due to the fact that the tests (were) on online and open note, it does not facilitate critical thinking or memorization. It just challenges one to be able to compile and locate information.”

“I think I learned some skills when it comes to reading scientific papers and how to see if there is reliable information that I can use from it. I would not say my critical thinking skills improved or changed much from this course.”

“Although I already had experience reading and using scientific journals and studies to conduct research, this class made me more comfortable and knowledgeable in doing so. I was able to apply principles I had learned about different kinds of studies, subjects, and data to the information we were learning in class. I feel that this practice of being up to date on current research will be valuable in my field as a future physician.”

Concluding Remarks

Based on the findings so far in comparing the two types of blended classes, both from the professor’s standpoint (amount of work, ease in delivery) and the students (improvement in grades, apparent improvement in critical thinking skills), both formats worked. Students liked the second blend format slightly more, perhaps because the active work was interspersed between a traditional lecture time-so both types of students got what they wanted for at least some of the course. In the second blend of the course, they were more likely to be tested on things that were part of the discussion (note the last student comment on the first blend of the class), and were told this, so again, students felt that the discussion was part of the class was useful, and would be tested on.

As the professor for this course, I felt that it was a little easier to ‘control’ the active participation part during the second blend because there was only one discussion question and it gave both me and the students a break from the lecture. It was also a little easier to come up with discussion topics for each lecture, rather than have an entire 75 minute lecture on one day and then have two-three related topics to discuss on the second day. However, the review questions were a useful feature, and might have contributed to the slightly higher exam scores in 2016 compared to 2017. I am in the process of planning for the spring 2018 course and plan to do a “third blend”, which will have two days of lecture/discussion like the second blend format, but inclusion of review questions on the second day of the week as well.

Learn More

Additional Readings and Websites

Every classroom is different (and really, every year the class itself seems a little different too), so what works for one might not work the same for another. Here are some other resources on blended classrooms, using interactive technologies, and developing questions/reflections.

What is Blended Learning?

Results from other case studies

- University of Southern Mississippi

- National Center for Academic Transformation-case studies

- List of case studies/exemplars

Technology

- TopHat (used in this case study)

References & Resources

Berrett, D. (2012). How “flipping” the classroom can improve the traditional lecture. Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from: https://www.chronicle.com/article/How-Flipping-the-Classroom/130857

Educause. (2012). Seven things you should know about flipped classrooms. Retrieved from: https://library.educause.edu/resources/2012/2/7-things-you-should-know-about-flipped-classrooms

Garrison, R.D. (2004). Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 7, 95-105.

Good, D.J. Practical metabolic nutrition : A systems approach to vitamins and minerals. p x, 323.

Hamdan, N.; McKnight, P.; McKnight, K.; Arfstrom, K.M. A review of flipped learning. http://www.flippedlearning.org/cms/lib07/VA01923112/Centricity/Domain/41/LitReview_FlippedLearning.pdf

About the Author

Deborah J. Good

Dr. Good was a first generation college student raised in upstate NY in a small town of under 10,000 residents. Her high school guidance counselor advised her to go into medical technology since she liked science, but after doing undergraduate research both at SUNY-Fredonia and during a summer research internship at the Lovelace Inhalation Toxicology Research Institute in Albuquerque, NM, she knew she wanted to become a scientist and help others discover research as well.

Since starting her independent laboratory, Dr. Good has secured over 1.77 million dollars in awards have supported her research, including monies specifically designed for student development. She has published over 50 journal articles and many books and book chapters on the genetics of body weight regulation. Dr. Good has also authored papers on teaching pedagogy, and completed two certifications for technology-enhanced online learning. Her passion for promoting research for undergraduates and minority students is evidenced, as she is PI of a grant that established a new summer undergraduate research program for HNFE and has mentored one VT Prep Scholar, one McNair summer scholar, and two minority high school students in the Ag Scholars program. Dr. Good is a co-PI on a just-awarded HHMI Inclusive excellence grant which will help to increase opportunities for first generation students. Dr. Good has trained 3 postdoctoral fellows, 16 graduate students and 37 undergraduate students over her career. At SUNY-Fredonia, where Dr. Good serves as Vice Chair of the Natural Sciences Advisory Committee, she has funded a molecular genetics laboratory, named for her family, with donations directly supporting undergraduate research.