Defining Games

In their groundbreaking work Rules of Play, Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman discuss the variety of ways in which scholars have tried to define the concept of a game. Various features of games such as being voluntary, not serious, uncertain, involving make-believe, and conflict, etc. have all been posited as components of a definition. Salen and Zimmerman finally decide on the following definition: “A game is a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome” (Salen & Zimmerman, 2003).

Further, the goal of game design is to produce a game that offers the player the opportunity for meaningful play. Salen and Zimmerman note that, “Meaningful play occurs when the relationships between actions and outcomes in a game are both discernable and integrated into the larger concept of the game” (Salen & Zimmerman, 2003). Discernable relations between actions and outcomes mean that the player can determine that if they do action A within the game, outcome B will result. Integrated relations occur when everything the player does and experiences within the game makes sense within the context of the game. In game-based learning, students are able to see that the educational content they receive and how they deal with it matters, it has meaning to the student independent of the paradigm of the classroom, within the context of the game.

This definition of meaningful play fits well within educational contexts, because in a well-organized learning experience, the learner must be able to see the connections between pieces of knowledge and understand how they fit into their context. If a physics student learns a particular formula as part of a good educational experience, then as part of that understanding, they also understand how to apply this knowledge in the real world, and how this formula fits in with other formulae in describing how the physical world works.

What is Game-Based Learning?

Game-based learning uses games, whether virtual or physical, and game-like simulations/role playing to create learning experiences that can engage students and effectively teach classroom content. Game-based learning can take multiple forms depending on the needs of the classroom. These may include such formats as:

- board games

- card games

- word games

- video games

- simulations

- role-playing games

- puzzles

Diana Oblinger (2006) also breaks down video games further into adventure games, puzzle games, role-playing games, strategy games, sports games, and first-person shooter games. There are also numerous ways to classify board or card games into further meaningful subdivisions. Board games can be race games, conquest games, turn-based strategy, abstract strategy, and many others. Card games include matching games, trick-taking games, and so on. This list is by no means exhaustive, as different types of games are invented all the time. Some games, such as the card game Fluxx, even play with the conventions of games themselves; in these games the rules and goals of play change with nearly every player turn.

Why use games?

Games can be used to 1) reinforce concepts learned in class, 2) to create greater engagement with course material, and 3) to provide multiple methods of approaching course material. James Paul Gee has long been the standard bearer for identifying the usefulness of games for producing effective learning experiences. He has identified numerous principles of video games that make them ideal for education. Some of these include (Gee, 2005):

- interaction—video games require a player to take part in order to play the game, unlike many learning experiences which allow the learner to take an inactive role

- risk taking—video games provide a low risk environment in which to try different approaches to problem solving; if one approach does not work the player can simply try another

- agency—players have an ownership in the outcomes and course of the game

- well-ordered problems—video games present problems in a way such that the difficulty level of what the player must solve starts at an easy level and becomes progressively more challenging

- situated meanings—all knowledge and experience in a video game is connected to the context in which the player finds him or herself

- systems thinking—players of a video game receive information and undergo challenges that are always mindful of the context of the whole game; all the learning is connected to the entirety of the system; there are no parts that exist in isolation

- performance before competence—players of a video game are taught skills that they use at a low level and practice over and over again until they achieve mastery at these skills

Gee has identified many additional other principles, tying effective game-based learning to the methodologies of effective educational experiences. Other researchers continue to add to the list.

How to get started with game-based learning

Game-based learning can be implemented at a range of levels, from simple game-like icebreakers that shake up the classroom environment to full-fledged classes being taught through a video game (ECON 201, University of North Carolina at Greensboro).

Figure 1: Econ 201, a videogame for college credit at UNCG

The specific type of game used will depend on several factors, including:

- educational purposes

- amount of time allotted and its place in the course

- size and type of class

- resources (budget, staffing, technology)

Diana Oblinger (2006) has some suggestions for linking the educational intent of the game to its genre:

- card games—memorization, pattern recognition, drill

- Jeopardy-style games—quick responses, factual recall

- arcade-style games—hand-eye coordination, visual processing

- adventure games—problem solving

Designing Approaches for Game-Based Learning

Consensus does not yet exist on the best way in which to design an educational game or game-based learning experience. One approach to getting started is to learn about the fundamentals of games. To learn about the basics of games and how they work, one of the seminal textbooks is Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals by Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman. Rules of Play looks at games, both physical and digital, and examines them from every angle, including rules, games as social play, the flow of information within games, the pacing of games, and more.

Van Eck (2006) notes that there are three general methods for getting started with game-based learning: repurpose an existing game, ask students to design a game, and build a game yourself. The first strategy for implementing game-based learning is to repurpose existing games, such as Civilization or SimCity. Such games are referred to in the literature as COTS (commercial off-the-shelf) games (Van Eck, 2006). The advantage of such an approach, especially with video games, is that it is often much less expensive than the laborious process of designing, programming, and producing a full-fledged video game. Designing a video game often involves teams of individuals, including instructional technologists, programmers, and graphic designers. Selecting a video game that already exists and adapting it for classroom purposes can generally be done on a fairly limited budget, especially if free or open source web-based games are used. The downside to such an approach is that the purpose of these games is never entirely educational, but for entertainment. As such, they are sometimes of limited use in an educational context, so selection of the appropriate game is crucial, and can be time-intensive, depending on the use to which the game will be put.

Another way of introducing game-based learning to a class is to have the students do the designing of games themselves. When putting together a game, much like putting together a presentation or lesson, students are required to focus on the details and interrelations of the knowledge they wish to convey in order to make an interesting and playable game. In his experience with requiring students to create their own games, Mr. Rice has received mixed results with this approach, and has learned that the main consideration is careful explication of the parameters of the game and expectations for the students.

The third approach is to design your own game. Moreno-Ger, Burgos, Martínez-Ortiz, Sierra, and Fernández-Manjón (2008) suggest an approach to game design with three essential phases: identifying pedagogical requirements, general design, and implementation. Their approach is somewhat limited to their chosen example of a digital game, but could be expanded to form a general approach to game design.

Identifying pedagogical requirements requires thinking about the material that students need to learn, how the game will fit into the class, and how to assess the learning taking place during the game. General design will include some of the above considerations for the genre of game, the game mechanics and rules, creating and assembling materials and resources, programming a digital game, and more. The implementation phase involves actually executing the plan, assessing the learning, and adjusting the game for future use.

The type and range of game design depends greatly on the resources one can muster in terms of the above mentioned skills of game design, programming, and graphic design. Mr. Rice has designed a web-based board game similar to Trivial Pursuit that can be adapted for a wide range of educational contexts. The intent of its design is to lower the barriers to classroom adoption of web-based games and to make it more available to educators with a limited range of technology skills. Because of the random nature of the question-and-answer content provided with the game, it is probably not best used to introduce classroom content, but to provide review.

Examples of Classroom Games

Mr. Rice has used games in a number of different courses to engage students in the classroom.

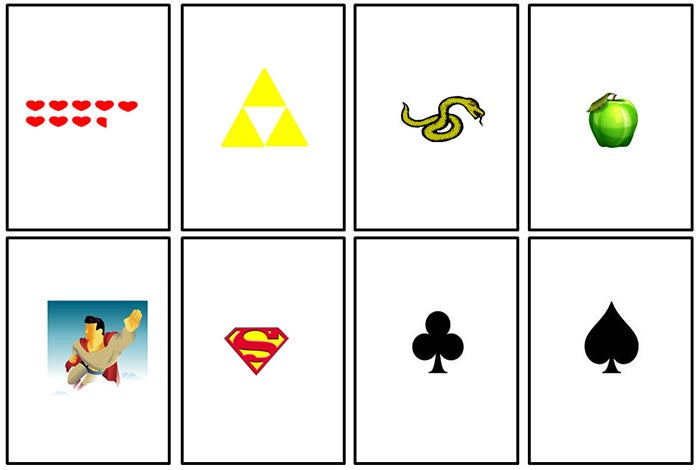

Example 1: Symbol Matching

A game-like exercise that Mr. Rice has used as an icebreaker on the first meeting of an introductory philosophy class involves dividing the students up into groups and giving each group a set of 32 cards with different symbols on each one.

Figure 2: Examples of symbol cards for icebreaker game

For this exercise, students are not given much guidance on what to do with the cards and they are simply told to impose an organizational scheme on the set in any way they choose. The cards can be matched up so that there are 16 pairs of cards that can be matched thematically (logos for Twitter and Flickr), symbolically (club and spade), and physically (left half of box matches with right half of box). Few groups of students match the cards up in exactly the way the pairs were set up. Some groups will match the cards into mixed groups of two, three, or four cards. One group created a story that utilized the content of every single card. Many of the symbols were intentionally chosen to have several meanings, and the importance of the exercise is to compare what the different groups propose. The ways in which people impose their own subjective meanings (the groups’ organizational schemes) onto the same set of objective facts (the cards) can then be discussed from the example of the exercise.

Example 2: Hobbes Games

One example of the classroom use of games to enhance student understanding of material is the Hobbes Game, which Mr. Rice has students play in an introductory philosophy course. In order to give students a feel for questions of ethics—Hobbes’ concepts of the “state of nature” and “the war of all against all”—the students are pitted against one another with the object of securing a grade for the assignment. The game takes place in three stages:

Caucus

During the Caucus stage, the rules of the game and the procedure for playing are explained, any questions that the students have are answered, and the students are encouraged to talk over what a good strategy for getting the best outcome might be. Students are also encouraged to make any moral arguments they might make based on previous classroom discussions of ethics, including Kant and utilitarianism. Students typically talk together in small groups at this stage, and it requires a bit of effort to get them to address the class with their ideas, but eventually a short discussion can be coaxed out of them.

Initial Grade Award

During the Initial Grade Award, students are paired up by using the playing cards distributed at the beginning of class. Each student is also given an index card. The cards are folded in half, and students are instructed to write their names on the outside of the card and once they have been paired up, they are asked to write either an A or a B on the inside of the card. They are not to allow any other student to know what grade they are writing. Then the instructor collects the cards from each pair of students and writes their names and grade on the board.

- If both players request an A, both will receive a 1.5

- If both players request a B, both will receive a 2.5

- If one player requests an A and the other requests a B the player who requested an A receives a 4.0. The player who requested a B receives a 0.0

Once all players have their names and scores on the board, the next stage begins.

Grade Readjustment

During this stage, any student is allowed to challenge any other student for their points. A challenger simply names the person they wish to challenge, and then assistance with the challenge is solicited. Any number of students can choose to assist either side of the challenge. A black Go stone is placed in a cup for every individual on the challenger side, and a white stone is placed in the cup for every individual on the challenged side. A student is then asked to draw a stone to designate the winning side. The losing side loses all of its points, which are then redistributed among every person on the winning side. Any fractions of a point beyond tenths, or above 4.0 are simply gone. Therefore, the longer the students challenge each other in order to better their own situation, the more overall points disappear from the system. Most students realize this is happening at least part way through the process and sometimes an equilibrium is reached. Of course, some students are still unsatisfied with their ending position and wish to continue challenging in order to get a better outcome.

At the end of the class, students are informed that those who are unsatisfied with the grade they “earned” through playing the game can improve it to a 4.0 by writing a short reflection paper on the game. Since almost all students do not achieve a 4.0 through the process of the game, Mr. Rice receives a large number of papers.

Finally, a portion of the next class period is used to discuss the lessons learned and reflections the students may have about the game. The instructor also asks about ways in which the game might be improved, made easier to understand, or more dynamic.

Example 3: Virtual Worlds Scavenger Hunt

To motivate students and encourage exploration, Mr. Rice used a simple scavenger hunt game in a set of virtual worlds for a class of first year students. The objective of the game was to introduce students to virtual reality. The online company Active Worlds allowed guests free access to dozens of virtual worlds. To play the game required some preparation on the part of the instructor, which involved visiting a number of worlds and looking for interesting things for the students to find. A list was created and points were assigned to the various items based on the perceived difficulty of finding them among all the various virtual worlds available to guest users. The students were placed into groups and asked to take screenshots of the items they found and place them in a collaborative Google Drive presentation. Here is an example of some of the items students were asked to find:

- Pictures of five different avatars in five different worlds (50 pts)

- List of possible dance moves (2 pts per dance)

- Picture of two signs in two different languages (neither one English) (25 pts +10 pts for each additional language)

- Picture of a cat (10 pts)

- Picture of a character from Sesame Street (50 pts)

- Picture of a non-human avatar (10 pts)

- Picture of an object that you have made, with your name on it (100 pts)

- Picture of a world from high up in the air (10 pts)

- Picture of two people talking with talk bubbles above heads (10 pts)

- Picture of sign saying “Welcome to Mars” (15 pts)

- Picture of fireworks (45 pts)

- Picture of yourself in 25 different worlds (150 pts)

- Picture of disco floor complete with disco ball (50 pts)

- Picture of your avatar in a vehicle (5 pts per different vehicle)

- Picture of your avatar in your own custom-made costume (50 pts)

Virtual Library Orientation/Scavenger Hunt

With a reorganization of the curriculum for education majors at Appalachian State University, students are required to have an orientation to the use of the Instructional Materials Center (IMC) at the Library. With 300-400 students per semester needing instruction on how to use the IMC, it was impractical to attempt to fill this instructional need with face-to-face classes. So an online tour and scavenger hunt video game was devised to provide this instruction. The game involves a virtual tour of the physical spaces of the IMC with 16 hidden “hotspots” with instructional content that must be found while looking through 360-degree panoramic pictures of the Library. Once all 16 puzzle pieces are found within the confines of the game, students are given the call number to a physical item that can be found in the IMC and asked to locate it to find its bar code. The barcode is then used to provide access to a quiz that students take on the content of the game in order to prove that they have passed the orientation. Students are given the first two weeks of classes in which to accomplish this task and may do so at any time.

This game is very successful for a number of reasons. First, the quiz results show that students were at least as well educated about the offerings of the IMC as they would have been after receiving a traditional presentation. Second, no class time (or instructor time) is taken up as the students complete the objectives of the game. Third, the game not only provides educational content about the resources and services of the Library, but players can also see and navigate the physical spaces of the Library within the confines of the application. Fourth, the students are then asked to use what they have learned to retrieve a real item from the physical Library. Finally, the students enjoy the format of the virtual tour/scavenger hunt, as shown by comments left in a formative survey at the end of the experience.

This game and its content is also open source and available for other educators to use in any way they wish.

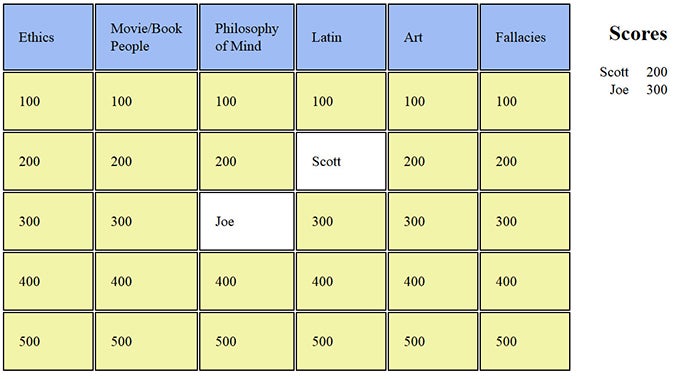

Example 5: Jeopardy Game Review

In Mr. Rice’s introductory philosophy class, students are given time during the last class period of the semester to review concepts and ask questions regarding class content in preparation for a comprehensive final exam.

Figure 3: Online Jeopardy Board Game

For the first few semesters of the class, students were generally reticent to ask many questions at this time, so the open review period was replaced with a Jeopardy style game with representative concepts and content that may appear on the final.

Students were given class participation credit for garnering points within the game and were encouraged to use their notes in class to assist recall. A simple JavaScript program to display the game board and keep track of student points was created and used specifically for this purpose. Instructions within the file explain how to change the categories to suit the educational need. Students seem to be more enthusiastic and proactive about reviewing the material in class while searching for answers to the questions posed during Jeopardy.

Other Examples of Games

- Little Big Planet, Shaun White Skateboarding, Guardian of Light, and Uncharted 2 to teach concepts in an introductory physics class (Mohanty & Cantu, 2011).

- Jenga used to teach about oppression in an undergraduate social work class (Lichtenwalter & Baker, 2010).

- Using role-playing exercises in history classes (Beidatsch & Broomhall, 2010).

- Using a board game as a peer mentoring tool to enhance student success in a nursing program (Sulpizi, Price, Yetto & Burris, 2014).

Summary

Game-based learning is a pedagogical practice that is often difficult to implement in the classroom, but has great rewards for the instructor willing to develop the practice. The use of games can represent some of the best implementations of UDL and good educational practice, making a real difference in the lives of students.

Pros and Cons of Game-Based Learning

Pros

- higher engagement and motivation

- better retention of classroom concepts

- engaging learners at different levels and types of learning

- flexibility to address in-class content

Cons

- requires a great deal of preparation and analysis to be most effective

- professors may be uncomfortable with different type of teaching

- students may not perceive games as serious instruction

Learn More

Literature Base

Editor’s Note: The Literature Base section of each College STAR module provides a brief summary of support for the instructional practice highlighted within the module. This is not an exhaustive literature review. It is designed to give the viewer an introduction to the literature about the module’s instructional practice. Please consider using the Learn More section of the module to supplement the information you obtain through this Literature Base summary.

Games have long been recognized as effective instruments for sound pedagogical practice. James Paul Gee (2005) writes in his research of the connections between videogames and education, drawing parallels between the features of games and good learning experiences. Gee has numerous writings that explore the various ways gaming is an effective instructional tool. Bizzocchi and Paras state that “games foster play, which produces a state of flow, which increases motivation, which supports the learning process” (Bizzocchi and Paras, 2005). The support for their effectiveness has a wide basis, as Van Eck (2006) notes “there are numerous other areas of research that account for how and why games are effective learning tools, including anchored instruction, feedback, behaviorism, constructivism, narrative psychology, and a host of other cognitive psychology and educational theories and principles.” One such study outlines the effectiveness of games using instructionist and constructionist perspectives (Kafai, 2006).

One core principle of adopting game-based learning is that different games should be selected for different objectives. Diana Oblinger (2006) notes that the type of game selected depends on the learning outcome the instructor wishes to achieve. There is no real consensus about the best ways to design or select a game for game-based learning purposes. European researchers have devised selection and assessment criteria for games (Dondi & Moretti, 2007). Moreno-Ger, et al. (2008) propose a three-step game design process which includes identifying pedagogical requirements, general design, and implementation. Van Eck (2006) describes three different approaches to using games: using commercial games, having students build games, or having educators build games.

There are numerous ways in the literature in which games have been used in educational settings. Board games have been used to teach nursing students about peer mentoring (Sulpizi, Price, Yetto & Burris, 2014) and social work students about oppression (Lichtenwalter & Baker, 2010). Video games have been used to teach such disparate subjects as physics (Mohanty & Cantu, 2011), economics (Brown, 2006), information literacy (Harris & Rice, 2008), mechanical engineering (Coller, & Scott, 2009), research methods and statistics (Boyle, MacArthur, Connolly, Hainey, Manea, Karki, & van Rosmalen, 2014), and ethics in engineering (Lau, Tan, & Goh, 2013).

The first step in integrating games into the classroom is to learn more about how games work. A discussion of game mechanics and rules can be found in Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals by Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman. The next step is to consider the pedagogical requirements of the classroom (Moreno-Ger, Burgos, Martínez-Ortiz, Sierra, & Fernández-Manjón, 2008) including integration, adaptation, and assessment. Additionally, consider the requirements and resources needed to design, select, and/or obtain the game, and make it successful. Finally, play! Games are fun!

References & Resources

Beidatsch, C., & Broomhall, S. (2010). Is this the past? The place of role-play exercises in undergraduate history teaching. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 7(1), 6.

Bizzocchi, J., & Paras, B. (2005). Game, motivation, and effective learning: An integrated model for educational game design. Proceedings of DiGRA 2005 Conference: Changing Views – Worlds in Play, http://summit.sfu.ca/item/281

Boyle, E. A., MacArthur, E. W., Connolly, T. M., Hainey, T., Manea, M., Kärki, A., & Van Rosmalen, P. (2014). A narrative literature review of games, animations and simulations to teach research methods and statistics. Computers & Education, 74, 1-14. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360131514000141

CAST. (2009). CAST UDL online modules. Retrieved from http://cast.org

CAST. (2011a). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.0. Retrieved from http://cast.org

CAST. (2011b). UDL guidelines version 2.0. principle I. provide multiple means of representation. Wakefield, MA: Author. . Retrieved from http://cast.org

CAST. (2011c). UDL guidelines version 2.0. principle II. provide multiple means of action and expression. Wakefield, MA: Author. . Retrieved from http://cast.org

CAST. (2011d). UDL guidelines version 2.0. principle III. provide multiple means of engagement. Retrieved from http://cast.org

CAST. (n.d.). About CAST: What is universal design for learning. Retrieved from http://cast.org

Coller, B. D., & Scott, M. J. (2009). Effectiveness of using a video game to teach a course in mechanical engineering. Computers & Education, 53(3), 900-912. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360131509001201

Dondi, C., & Moretti, M. (2007). A methodological proposal for learning games selection and quality assessment. British Journal of Educational Technology, 38(3), 502-512. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2007.00713.x/abstract

EnACT. (n.d.). 14 common elements of UDL in the college classroom.

Evans, C., Williams, J., King, L., & Metcalf, D. (2010). Modeling, guided instruction, and application of UDL in a rural special education teacher preparation program. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 29(4), 41.

Gee, J. P. (2005). Good video games and good learning.85(2), 33. http://www.jamespaulgee.com/sites/default/files/pub/GoodVideoGamesLearning.pdf

Immordino-Yang, M. H., & Damasio, A. (2007). We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education. Mind, Brain, and Education, 1(1), 3-10. doi:10.1111/j.1751-228X.2007.00004.x

Jones, S. (2003). Let the games begin: Gaming technology and entertainment among college students, Pew Internet and American Life Project. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2003/07/06/let-the-games-begin-gaming-technology-and-college-students/

Kafai, Y. B. (2006). Playing and making games for learning instructionist and constructionist perspectives for game studies. Games and Culture, 1(1), 36-40.

Lau, S. W., Tan, T. P. L., & Goh, S. M. (2013). Teaching engineering ethics using BLOCKS game.Science and Engineering Ethics, 19(3), 1357-1373. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11948-012-9406-3

Lichtenwalter, S., & Baker, P. (2010). Teaching note: Teaching about oppression through jenga: A game-based learning example for social work educators. Journal of Social Work Education, 46(2), 305-313.

Mohanty, S. D., & Cantu, S. (2011). Teaching introductory undergraduate physics using commercial video games. Physics Education, 46(5), 570. http://arxiv.org/pdf/1107.5298.pdf

Moreno-Ger, P., Burgos, D., Martínez-Ortiz, I., Sierra, J. L., & Fernández-Manjón, B. (2008). Educational game design for online education. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(6), 2530-2540. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0747563208000617

National Center on Universal Design for Learning. (2011). About UDL. Retrieved from http://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl

Oblinger, D. (2006). Simulations, games, and learning. ELI White Paper.

Rose, D. H., Harbour, W. S., Johnston, S. G., & Abarbanell, L. (2006). Universal design for learning in postsecondary education: Reflections on principles and their application. Journal of Postsecondary Education & Disability, 19(2) Retrieved from http://cast.org

Rose, D. H., & Meyer, A. . Teaching Every Student in the Digital Age: Universal Design for Learning. Retrieved from http://www.cast.org

Rose, D., & Dalton, B. (2009). Learning to read in the digital age. Mind, Brain, and Education, 3(2), 74-83. doi:10.1111/j.1751-228X.2009.01057.x

Salen, K., & Zimmerman, E. (2004). Rules of play: Game design fundamentals MIT press.

Sulpizi, L., Price, N., Yetto, D., & Burris, J. (2014). The use of gaming as a peer mentoring tool for student success strategies. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 9(3), 139-143. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1557308714000353

UDLCAST. (2011). Introduction to UDL. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MbGkL06EU90&feature=relmfu

Van Eck, R. (2006). Digital game-based learning: It’s not just the digital natives who are restless.EDUCAUSE Review, 41(2), 16. http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/digital-game-based-learning-its-not-just-digital-natives-who-are-restless

Additional Resources

APA style: A DOI primer. Retrieved from from http://blog.apastyle.org/apastyle/2009/09/a-doi-primer.html

CAST: Center for applied special technology. Retrieved from http://www.cast.org

CrossRef. (2002). DOI resolver. Retrieved from http://www.crossref.org

Dondlinger, M. J. (2007). Educational video game design: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Educational Technology, 4(1), 21-31. http://pdf.aminer.org/000/589/258/best_practices_in_corporate_training_and_the_role_of_aesthetics.pdf

Gee, J. P. (2007). Good video games good learning: Collected essays on video games, learning, and literacy P. Lang New York.

Gee, J. P. (2007). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy.: Revised and updated edition Macmillan.

International DOI Foundation. (2012). Resolve a doi number. Retrieved from http://www.doi.org

Salen, K., & Zimmerman, E. (2004). Rules of play: Game design fundamentals MIT press.

Squire, K. (2011). Video games and learning: Teaching and participatory culture in the digital age. technology, education–connections (the TEC series). ERIC.

About the Author

Scott Rice

Belk Library and Info. Commons

Appalachian State University