MERGING SILLY AND SERIOUS FOR CREATIVE EXPRESSIONS OF LEARNING

Contents

Introduction

This module offers fun ways to engage students and a fast, low-stakes way to express and assess student learning each week. Students, individually or in groups, summarize the main lesson they learned in class that week by using a series of creative, expressive communication techniques, which facilitate multiple means of expression and engagement. I describe the instructional strategy for engaging students in otherwise wearying or intimidating courses.

The senior capstone course in sociology is known among students for being challenging and tedious. They must pass the capstone course with a C or better to graduate and, unlike many of their other courses, it is not topic-driven and thus not so relevant to their life experiences and interests. I therefore wanted to find ways to engage students and acknowledge the difficulties and pressures of this rigorous required course by introducing an affective dimension to the learning process. Further, realizing that I did not always know if the lessons I sought to impart were being understood well, I wanted to find ways to assess how well students were learning what I was teaching each week.

While my sociology course is a traditional face-to-face class, the devices I share can easily be used in online environments as well. This module provides a series of templates that teachers can download and use, electronically or on paper, online or face-to-face, to engage students in fast and fun reflective summaries of that day’s or week’s lesson. While I used these as quick in-class assessment activities, they could also be assigned as homework activities.

Objectives

This module offers instructors:

1. concrete techniques, including downloadable image templates, that they can use to have students quickly and creatively express what they are learning; and

2. the reasons behind the use of those techniques to engage a variety of styles of student learning and expression.

UDL Alignment

This module aligns with: Principle II, Provide Multiple Means of Action or Expression; and Principle III, Provide Multiple Means of Engagement.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression

Encouraging students to express their learning using a variety of creative forms meets the principle of Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression. Providing alternative modalities for expression, including creative and humorous modalities, in addition to the traditional activities and assessment methods, offers a wider variety of students a chance to express knowledge, ideas, and concepts in the learning environment.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Engagement

Student engagement is easier to encourage when they find the form of communication less intimidating. While students do not always understand the serious world of literature reviews, theory, and formal citations, they do tend to understand the structure of communicating in the forms I introduce in these exercises–from Internet memes to thank-you notes. Using creative, expressive communication techniques provides Multiple Means of Engagement by asking students to express their learning in low-stakes ways that start with a structure they already find familiar. Using silly methods of communicating the serious makes the learning environment less intimidating, helping to create a safe space for learners.

Instructional Practice

Forms of Creative Expression for Students

I had students form groups of three that stayed together all semester. I referred to them as “teams” and had each come up with a team name for the semester. The group format encourages discussion and collaboration, and minimizes the time it takes to share expressions at the end. While I had students work in groups to do these creative expressions collaboratively, instructors teaching online might have students do these individually and then share with the class in an online forum.

Knowing that they were going to share their creation with the whole class added another layer of motivation for students to be creative, funny, and smart. They also enjoyed seeing what the other groups came up with. Inevitably, each group offered a different sense of what the most important lesson was. Teachers or students can select the specific creative means for expressing their learning to tie thematically to the material. The entire process takes just ten minutes.

Each expressive form is described here, and then the accompanying images/templates, where necessary (and marked with *), are included in the next section of this module so that instructors can download and use for class. A note on copyright. Many teachers understandably wonder about copyright infringement when they use images. The images provided here are either my own creation or were labeled for noncommercial reuse. The images below are shared for noncommercial instruction or curriculum-based teaching by educators to students at nonprofit educational institutions. They are not for commercial use or distribution beyond the classroom. (See United States Copyright Office in this module’s resource list.)

FORMS OF CREATIVE EXPRESSION

T-Shirt.* I asked my students to imagine that they had to wear a souvenir T-shirt from my course that week, and to write a message on the shirt based on what they’ve been studying that week. I’d say to them, “You went to Professor McCaughey’s class this week and all you got was this stinkin’ T-shirt. What would the T-shirt say?” I passed out images of T-shirts and student teams marked their shirt with their message. This is particularly useful for capturing threshold concepts (see Meyer, et al [2010]).

Emoji. Particularly useful for enabling students to express emotion in a familiar, safe, and friendly way, have students express how they feel about an assignment or task using three Emoji or fewer. They can then post these for the group using Padlet or to a course online discussion forum. Alternatively, of course, they can send them to the teacher who can display or otherwise share them all on paper or electronically.

Internet Meme.* Internet memes are concepts, images, or catchphrases that spread throughout social media. When I started this, Ryan Gosling memes with feminist catchphrases were the current trend. Teachers can capitalize on whatever meme is trending that semester and ask students to make the most important thing they learned that week into an Internet meme. Cat memes are always popular so they remain a good fallback meme. (See the Meme Generator in the Resource List.)

Tweet.* Having students boil down a main point into a Tweet is an easy way to check their understanding of many different types of lessons. Students are familiar with Twitter and its 140-character limit provides a structure to that which you are asking them to write. I gave each student team a picture of a blank Twitter post and each group decided what they wanted to Tweet. Interestingly, without any instruction from me, students all added hashtags to their Tweets, which themselves were humorous and enabled them to expressive the affective dimension of what they were doing in class. In some cases, student teams added words from a previous week’s exercise as their hashtag. Some groups included their team name as a hashtag.

Facebook Status Update.* Similar to a Tweet, the Facebook status update is an activity that works for a variety of courses and lessons. I provide the image of a Facebook homepage with a blank status update and ask each student group to decide on how they would express the most important lesson of the week as a status update. This can also be used to express the affective dimension of something students are learning.

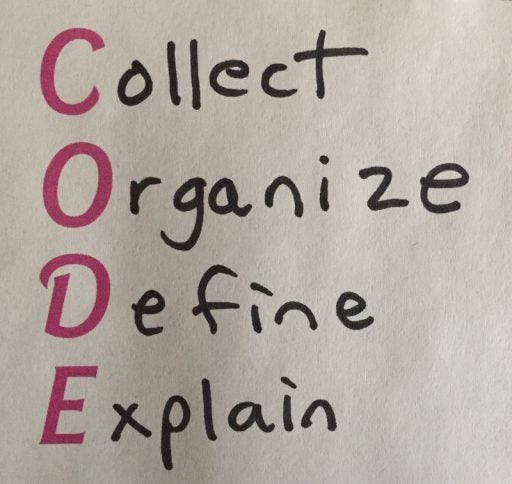

Acrostic Poem. An acrostic poem creates sentences out of the first letter of each word that students are learning. It is useful for helping students remember something important. The best time to ask students to devise an acrostic poem is when they need to remember the structure of a formal paper or a policy. I used this device when my students were learning about coding data. Each group made an acrostic poem for the word CODE. One group wrote, “Create your Own system for Doing Effective evaluation.” Another wrote, “Categorize your data, Organize into themes, Decide what they mean, Evaluate the research.”

Figure 1: Sample student work – an acrostic poem

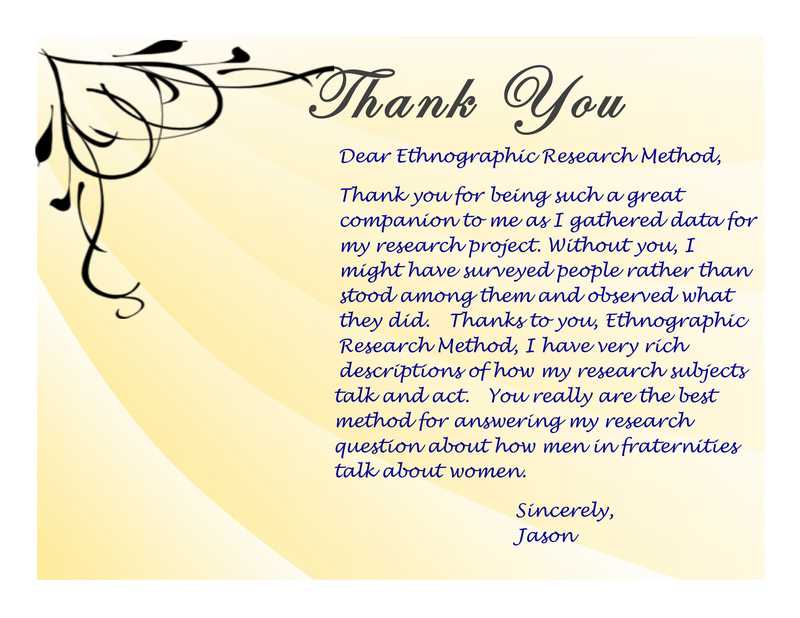

Formal Thank-You Note.* Formal thank-you notes are brief and exceptionally polite. Students are not used to writing them but here have a chance to write such a note to a theorist, author, entity, or concept. They can use the stiff, stuffy style of a formal thank-you note to thank the author or concept for something they’ve learned from her/him/it. Simply pass out small notes with a “Thank You” design preprinted on them. Student teams decide whom, or what, to thank based on what was most relevant that week. For example, here is a thank-you note related to a section about sociological research methods: “Dear Ethnographic Research Method, Thank you for being such a great companion to me as I gathered data for my research project. Without you, I might have surveyed people rather than stood among them and observed what they did. Thanks to you, Ethnographic Research Method, I have very rich descriptions of how my research subjects talk and act. You really are the best method for answering my research question about how men in fraternities talk about women. Sincerely, Jason.”

Figure 2: Thank You note sample

LOL My Thesis. Taken from the website, “LOL MY THESIS” (http://lolmythesis.com), in which graduate students offer witty simplified versions of their graduate theses (e.g., “Sand Washes Away. Don’t Build Important Stuff On It”), I shared some of these with students and challenged them to come up with their own humorous synopsis of their findings. (This was one activity they did not do in groups.) Since my students were doing their own research projects, and were supposed to be learning how to communicate about research to multiple audiences, this worked to get them to practice paring down their work to highlight main points. For example, my students came up with: “People think they know the causes and warning signs for school shooters, but they don’t”; “Campus police are mean, OK? Students like them, until they meet them”; and “The Internet is a scary place for women, Tumbler is slightly less scary, men are outraged.” The LOL My Thesis activity would also work for students who need to summarize the findings of other studies they are reading. They could create these summaries individually or in small groups.

What Would Yoda Say?* Yoda from Star Wars is known for his unique way of phrasing bits of wisdom (e.g., “Patience you must have, my young Padawan”), and is of course familiar to almost all students. Asking students to summarize the most important lesson from that week’s class in the way Yoda would say it provides a fun challenge that classmates will enjoy creating, and listening to (or reading) when fellow students offer their own.

Tattoo.* I provided the images of body parts with tattoos that till needed words added. I asked students to decide what from this course I wanted them to remember for the rest of their lives. “If I could make you tattoo it onto your body for you to wear for the rest of your life, what would the tattoo say?” This is useful for having students decide what the life value of the course is.

Haiku. While creating great haikus is truly an art, the 3-line, 5-7-5 syllable structure of this Japanese poetic form makes it a useful device for creating a concise, but high-impact, statement. Although a typical haiku contains a “season word” to express the time of year, you can have your students be sure their haikus specify something you designate (related to what they are learning). Like the traditional haiku, your students’ haikus are meant to produce sudden enlightenment or illumination.

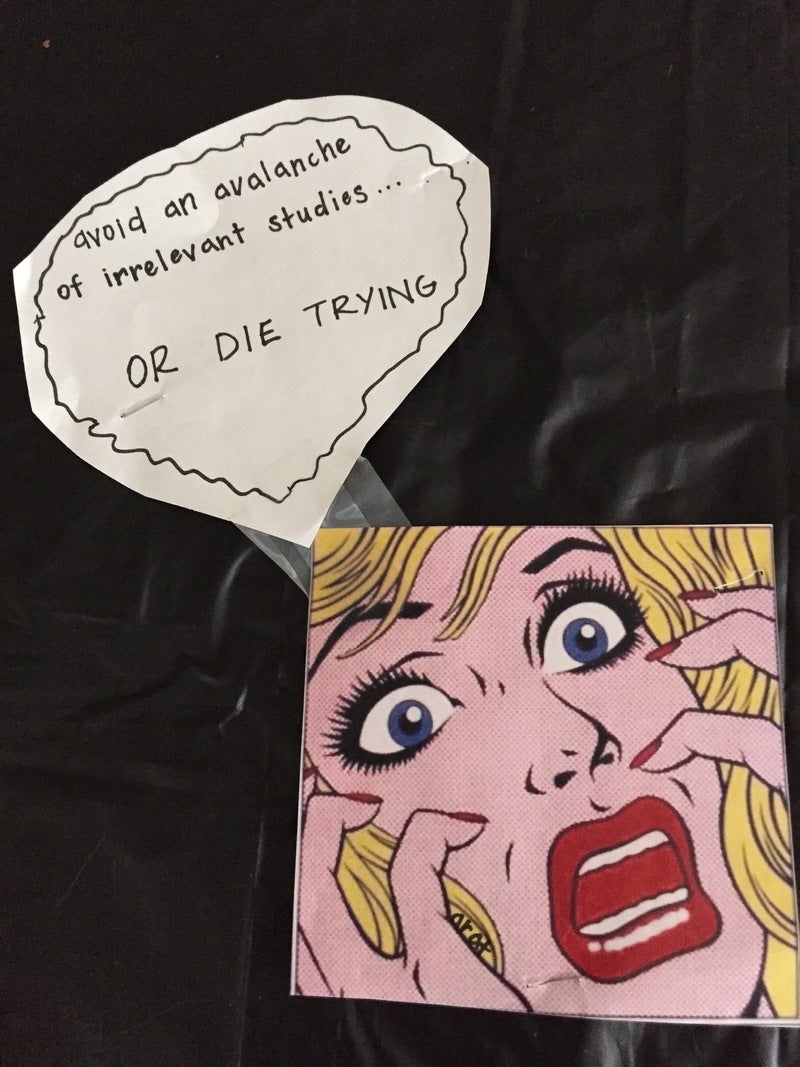

Pop-Art Comic.* Mid-century pop-art comics, emblematized by Roy Lichtenstein’s famous painting, “Drowning Girl,” combine recognizable imagery of sad and anguished people with speech balloons. Students enjoy the tongue-in-cheek style of these cartoons, writing their message in the speech bubble of the single-frame comics I provide, often expressing their own anguish over the difficult assignments before them.

Figure 3: Pop-Art Comic

Bumper Sticker.* The ubiquitous 12- x 3 –inch sticker makes a statement to others around your car (or your computer, or notebook, or any of the many places people now place bumper stickers). Students enjoy making their course-related announcement in this classic form.

The Ten Commandments of _______. I asked each small group of students to come up with one “commandment” to capture what they learned about a specific topic. (If you don’t have ten groups, you can have each group come up with more than one commandment.) This is particularly useful for underscoring specific rules and requirements, such as the use of a particular citation style, the safety standards of a lab, or the ethical code related to the students’ chosen profession. I used images of the iconic statues on my own campus as the image backdrop for the commandments students wrote. You can consider using an iconic image from your discipline or from your own campus.

Writing on a Cake.* I provided a variety of cakes with nothing written on them, asking students what they would write on their cake. I found that students enjoyed getting to select a cake from a variety of shape and color options. Each group then decide on their message and used a marker to write their message onto their cake. This exercise was useful in my writing-intensive course when I had to emphasize the importance of following directions (such as style guidelines for their given major) and the importance of grammar. As a way to show students why both writing structure and understanding directions are important to writing, I showed them pictures of mistakes written in frosting on top of people’s cakes. For example, one cake read, “Happy Birthday Brain!” (instead of “Happy Birthday Brian!”) and another read, “Happy Birthday Zoe with 2 Dots Over the O!” and still another read, “Happy Anniversary with Sprinkles All Around It!” I then used the cake decorating exercise for the students’ expression of the most important lesson of that week.

Interpretive Dance. I asked each group to create a brief, coordinated movement that would represent a concept or idea they had learned. Each group can decide the concept to dance/act out or the teacher can give each group a concept to dance/act out. I have shown students an example of an entire science dissertation being expressed as a dance, from the “Dance Your Ph.D.” contents (see resource list). In order to do this exercise—which takes some students beyond their comfort zone—students must first decide what the concept really means and how to convey that meaning nonverbally. If in a group, they must collaborate on how to coordinate their movements into one holistic way of expressing meaning.

Feedback Cards. On days when students present their own work in front of the class, I passed out a stack of standard note cards to each student, telling them that their job would be to write one to five words on the card that captured the best idea or technique of their classmate’s presentation. Students gave their feedback cards to their classmates at the end of the period. Feedback cards encouraged students to be attentive and positive audience members to their fellow students. Knowing that they had to write something summative and reflective on the card after each student’s presentation, they paid attention and looked for the positive. This worked to assure each nervous presenter that their fellow students were engaged in a sort of unconditional positive regard (while, of course, the instructor was going to be evaluating them more critically and issuing a grade). The presenters truly enjoyed receiving the bits of positive feedback and the listeners learned a new way to pay attention.

Learn More

Literature Base

Just as students comprehend information that is presented to them in a variety of ways (National Center on UDL, Principle I, 2011), students differ in how they express what they know (National Center on UDL, Principle II, 2011). The point is that students can reflect on, capture, and express some of their lessons using multiple creative means. These expressions also allow the instructor to see how the students are processing the information offered and how well students understand the material presented. They are a fun way for instructors to check in with students.

Students get engaged — excited about and interested in what you’re teaching— in a variety of environments, depending on the learner. (National Center on UDL, 2011). Engaging students emotionally in some way helps students learn (Immordino-Yang & Damasio, 2007; Rose & Dalton, 2009). My creative, reflective assignments engage students at the level of affect, allowing them to use humor and express not just what they learned but how they are feeling about the work they have to do. For example, just before their 30-page research paper was due, I asked students to describe how they were feeling about completing the task in three Emoji or fewer. This gave them permission to share their feelings of panic, or joy, in a lighthearted way they could also laugh about.

A variety of factors influence a learner’s affect, and therefore what activities and approaches will engage a student, including neurology, culture, personal relevance, and background knowledge (National Center on UDL, Principle III, 2011). Providing a variety of means for expressing learning throughout the semester enables instructors to reach a variety of students.

Adding silly forms of creative expression to serious ideas and projects encourages students to enjoy their focus on learning. In the essay “Silly Theory,” J.A. Stein (2012) writes about the learning strategies they employed in graduate school: “Playing silly games with serious ideas provided us with a way to lavish attention on the scene of our learning.”

Inserting some humor and silliness into a tough course, which many take so seriously that they are stressed out, can offer a kind of counter-snobbery that might encourage students who feel alienated from the course or who are about to quit because they think it’s too difficult. Specialized courses often contain so much of their own jargon and rules that students, particularly nontraditional students and students with learning challenges, can feel like outsiders being asked to talk a talk and walk a walk that feels very foreign to them. By offering a set of communication forms that students are familiar and comfortable with, students are invited to link something they already know to something that is more intimidating.

At the same time, harnessing many of the popular forms of communication in our world today—from bumper stickers to Internet memes—encourages students to replace the usual banalities on their Facebook pages with important ideas they are learning about.

In addition to adding some lightness to serious, and seriously rigorous, courses, these creative forms of expression allow one way for students to connect emotionally to what they are learning.

Additional Resources

Below, you will find the graphics referenced in this module that you can use with your students.

References & Resources

Meme Generator. https://imgflip.com/memegenerator

Meyer, J. H. F., R. Land, & C. Baillie (Eds). (2010). Threshold Concepts and Transformational Learning. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

National Center on Universal Design for Learning. (2011). About UDL. Retrieved from www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl

Rose, D. H., & Meyer, A. Teaching Every Student in the Digital Age: Universal Design for Learning, http://www.cast.org

Stein, J. A. (2012). “Silly Theory.” Avidly: Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved from http://avidly.lareviewofbooks.org/2012/11/20/silly-theory/

UDLCAST. (2011). Introduction to UDL. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MbGkL06EU90&feature=relmfu

United States Copyright Office. n.d. “Reproduction of Copyrighted Works by Educators and Librarians.” Circular 21. https://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ21.pdf

About the Author

Martha McCaughey

Prof. Martha McCaughey is a sociology professor at Appalachian State University. A late-career academic, she sought ways to make her sociology capstone class more interesting for both her students and herself. As a creative person who enjoys being silly, and having recently taken a series of graduate courses in Appalachian’s Expressive Arts Therapy program, she designed a series of fun and creative ways for students to express what they were learning, adding lightness to an intimidating course.