Optimizing Engagement and Self-Directed Learning with Mindfulness

Contents

- Introduction

- Objectives

- UDL Alignment

- Instructional Practice

- Mindfulness Practices: Engaging Observation and Inner Attention

- Readings: Engaging the Cognitive

- Reflective Dialog: Engaging Socially

- Insight Journals: Engaging Self

- Meditation: Engaging Strategies for Coping and Reducing Distractions

- Guest Speakers: Engaging with Community

- Assessment of Mindfulness and UDL Outcomes

- Conclusions

- Learn More

- References & Resources

- About the Author

Introduction

Winifred Gallagher, author of Rapt: Attention and the Focused Life (2010) theorizes that “Your life – who you are, what you think, feel, and do, what you love – is the sum of what you focus on” (p.1). Mindfulness is a process of practicing the art of attention. It holds the promise of engendering focus, presence, and receptivity along with an inner perspective that supports flexibility of mind, non-judgmental self-awareness and reduction of stress and anxiety.

This case study highlights multiple means of engaging students with processes of mindfulness throughout a college course on leadership. Mindfulness processes and evidence of student achievement in this area are not situated as a gradable components of the class, instead, mindfulness outcomes are integrated into the class as a mode of inquiry, an experiential process with no right or wrong answers, no rubricized criteria, and feedback is given as affirmation and encouragement. The UDL goal of providing multiple means of student engagement and internalizing self-regulation intersect with several experiential aspects of the classroom mindfulness practices. Additionally, engaging students in foundational mindfulness practices creates opportunities for self-regulation, reflective self-assessment and the development of personal coping strategies.

Objectives

This case study will describe the instructional process and practices for a college course that implemented mindfulness as an explicit instructional strategy. Descriptions of course activities and students’ reflections on their budding mindfulness skills will draw relationships to several dispositional and cognitive UDL goals.

After reading this case study you will be able to:

- Describe multiple means of engagement facilitated by mindfulness activities.

- Consider classroom mindfulness exercises and discussion prompts that support self-regulation.

- Explore methods of feedback and assessment that emphasize mindfulness in the college classroom

UDL Alignment

Mindfulness & Multiple Means of Engagement

The means of engagement explored in this course include cognitive, emotional, social, and creative participation by the students. Throughout the course mindfulness practices are integrated in the students’ experiential learning. Students’ reflective journaling, class discussions, and peer sharing are areas where mindfulness outcomes are observable. The following descriptive scenarios demonstrate how the teacher situated mindfulness to provoke engagement with students and support the internalization of self-regulation through self-awareness. Additionally, students responded with multi-layered representations of their learning that included written, verbal, and artistic work.

Multiple Means of Engagement: Course Activities and Assignments

The course selected for this case study is entitled “Contemplative Leadership and Personal Transformation”. An excerpt from the course description states “Using phenomenological research methods and introspection students will reflect on methods of personal transformation intended to support well-being, personal growth, stress reduction, meaning making, insight, and leadership skills.” Using first – person inquiry students reflect on their experiences in practicing mindfulness throughout the course. They also develop a cognitive context for mindfulness practices in contemplative leadership from both historical and cultural perspectives. Students are supported in establishing a personally selected mindfulness practice for eight weeks. They chronicle their practices through insight journals. Additionally, they participate in facilitated reflective dialog and readings to widen their understanding of mindfulness in terms of leadership and well-being.

Instructional Practice

Mindfulness Practices: Engaging Observation and Inner Attention

The primary mindfulness component of the class is an eight-week commitment by each student to a daily, self-selected mindfulness practice. Students are encouraged to select their own mindfulness practice to accommodate levels of interest and challenge that they individually sought. Student practices included, drawing, walking, running, being in nature, tending to plants, music, speaking, dance, and positive daily affirmations. For example, one student worked all semester on designing and drawing a set of Tarot cards that expressed personal stages of growth, identity, and their reflections on deeper insights that mindfulness enfolded in the drawing process.

Figure 1: Student drawings on blank playing cards

Practicing mindfulness required a commitment to engage with the activity without judgment and to simply observe their own experience from a place of neutrality and curiosity. Aiming towards a daily practice reinforced self-discipline and accountability while setting the stage for meta-cognition and self-awareness. Working towards non-judgmental self-observation provided a path toward self-acceptance and self- efficacy. We can see self-regulation emerging through the end of semester reflections. When asked “How has our work in mindfulness, meditation, or contemplative practices in this course helped you gain self-awareness?” a student reported the following: “Working on a personal practice made me work on self-exploration and helped me understand why I am the way I am.” Another student acknowledged, “I gained a better sense of self-identity b/c I lost the dependence on conformity and others acceptance.” As students balanced their commitments to personal practices with the multitude of demands on their time, energy and attention many also found sources of resistance that revealed habituated assumptions and patterns.

The most powerful aspects fully experiencing and acknowledging any resistance to practice occurred when they are simply able to bring the nature of the resistance into the forefront of their awareness. They realized they could choose to remain in the pattern or they could choose to stick with the practice. This happened for each student numerous times over the course of eight weeks, building towards the skills that result from autonomy and resilience. One student concluded, “It showed me that I was not as self-aware as I previously thought mainly because I was trying to avoid it. This class helped me by making me face the things I did not want to face.”

Readings: Engaging the Cognitive

The reading assignment included weekly readings from the text Finding the Space to Lead: A Practical Guide to Mindful Leadership (2015) by author Janice Marturano. During the first two weeks of the class students read about mindfulness and leadership practices to develop a working understanding of mindfulness practices and its practical purposes. This assisted students who are unfamiliar with mindfulness to gain secular, cognitive, grounding in the real world applications of these practices. The book provided examples of self-awareness and mindfulness practices in leadership and work-related scenarios. Students leveraged the readings by taking notes from the chapters and posing questions they had about the readings.

Reading notes are a graded component of the course and required students to capture at least five highlights or quotes from the chapter along with two or more questions that the reading raised for them. The chapter notes and the students’ questions are the focus of one of the two weekly classroom discussions. The book provided a common springboard for students to engage with the cognitive and applied aspects of mindfulness in the context of their career goals and social lives. When asked “How has our work in mindfulness, meditation, or contemplative practices in this course helped you become more resourceful or knowledgeable?” A student commented, “I am more resourceful in many ways. I know more about myself now than I ever did. I have so much more knowledge about myself that I can lead and trust even better than before. I have gained knowledge from my other classmates as well!”

Reflective Dialog: Engaging Socially

Fink (2018) recommends building in opportunities for students to participate with in-depth reflective dialogue that provide space to reflect on the significance of what they are learning and how they are learning. Using Parker Palmer’s “Circle of Trust” method outlined in his book A hidden wholeness: The journey towards the undivided self (2004) students worked with the practice of listening without judgment. This is a first step in creating a sense of community and safeness. Students also learned the meaning of equanimity and neutrality throughout several sessions of deep listening. They practiced listening by honoring an attitude that did not try to “fix” or advise, or save others, but instead simply supported furthering the speaker’s own inner process by asking open, honest questions. Deep listening is encouraged in being present with both others and self. A student reflected, “I have greater understanding of communication and being mindful of how my words might affect a situation. I’ve become more confident in my words within the classroom setting.”

Practicing the principles outlined in Parker Palmers Circles of Trust facilitated students working toward a non-judgmental and neutral positions in relation to their own self-observations and moved them towards a comfort level in free writing within reflective journals. These classroom experiences reinforced a safe place for learning and becoming for all students. These activities help foster community and a sense of belonging in the classroom.

Insight Journals: Engaging Self

Each student submitted a written weekly journal that captured their own experience of their chosen mindful practice. They are encouraged to record their observations and non-judgmentally chronicle their insights and their resistance as they practiced mindfulness. The instructor reinforced neutral self-observation by illustrating the difference between self-consciousness – the feeling that I may be wrong or should be doing something differently to fit in – and chronicling the simple awareness of what is occurring in rich detail. This practice of facilitating a neutral narrative reinforces and encourages equanimity, balance, and self-acceptance.

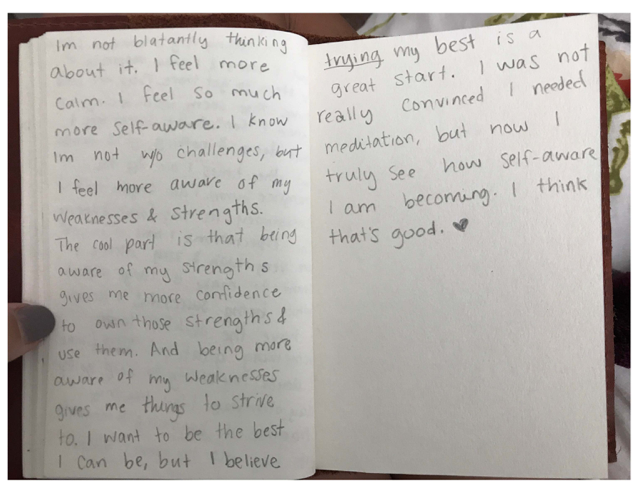

Figure 2: Sample photo of a students Insight Journal

Students also share with the class to the degree they are comfortable, many of their observations from their personal journals during the classroom discussions. The instructor facilitated these discussions initially and toward the end of the course students practiced facilitating the discussions with the skills they learned in the Circles of Trust practices. Becoming more resourceful and receptive, as well as developing a heightened salience of personal goals & objectives, are enhanced through the insight journals. Student comments related to this included, “I have learned that I have a lot of the answers in myself already. I’ve also learned to trust myself and my instincts.” Self-reflection coupled with daily practice provided the students with a method of noticing and accounting for their own personal growth over the short timeframe of a semester.

Meditation: Engaging Strategies for Coping and Reducing Distractions

Another essential classroom practice of mindfulness involved five to seven minute meditation sessions that ranged from silent meditations, guided loving kindness meditations, and focused attention on breath. The meditations are invitational in nature. The instructor first described the type of meditation that would be offered and then invited students who wanted to participate to join the process. Students who felt physically, emotionally, or spiritually uncomfortable with the described meditation for any reason could leave the class without question or penalty for the time period in which we practiced. Although meditation is not emphasized as the primary mindfulness component, students are also encouraged explore their own personal meditation practice and bring it to the class.

We practiced several student lead meditations with music, visuals, movement, and guided narratives that supported student ownership and honored a variety of meditative modalities. Both mindfulness and meditation are framed as a secular practice that guide students in developing focus, receptiveness, equanimity, compassion, and self-awareness. These meditation practices also provided students with skill sets to reduce stress. When asked “How has our work in mindfulness, meditation, or contemplative practices in this course helped you reduce stress or anxiety?” A student comments, “I have learned that when I have a panic attack, nature can be a resource.” Another student notes, “Meditating takes time and not always easy to start, but once I begin I fall into moments of effortlessness.” At one point in the semester students are asked if they wished to continue the short meditations and their answer unanimously “Yes”! A few minutes of stillness and relaxation is overwhelmingly welcomed.

Guest Speakers: Engaging with Community

Other supplemental classroom activities included guest speakers that addressed their professional relationships to mindfulness practices. Speakers included a nursing instructor, a Tai Chi teacher, a writer, graduate student, and a minister. Students also spent one class session walking a labyrinth.

Figure 3: Woman arranging cloth at the center of a labyrinth

After the labyrinth walk they participated in a guided expressive arts exercise that involved drawing their interpretation of the experience and sharing their drawings.

The final integration paper for the course included their library research on a contemplative leader, the highlights from their experiential mindfulness efforts, and the development of a personal contemplative leadership framework, which included their principles of contemplative leadership. As a conclusion for the course each student prepared a creative piece that captured his or her experiences and learning in the class. They had the freedom to choose their medium and method of presentation. Students expressed their experiences with presentations that included dance, music, drawings, photos, and plants they had grown.

Assessment of Mindfulness and UDL Outcomes

Grades are assigned for reading notes, papers, class participation, and journal completion. Grades rarely capture the affective domain and the inner process of the learner. The instructor noted evidence of learning that developed from mindfulness practices through the students’ moments of insights, self-awareness and their acknowledgement of newly minted self-knowledge.

To assess the student experience a process of practicing mindfulness the following open-ended questions are given to students on the last day of class. Each question is posed at the top of a blank sheet of paper and students are given approximately 20 minutes to respond. These questions corresponded directly with several of the UDL outcomes.

By considering the student responses to prompts such as those proposed herein, teachers can reasonably draw their own conclusions on the degree to which the intention of related UDL goals are achieved.

- How has our work in mindfulness, meditation, or contemplative practices in this course helped you gain self-awareness?

- How has our work in mindfulness, meditation, or contemplative practices in this course helped you become more resourceful or knowledgeable?

- How has our work in mindfulness, meditation, or contemplative practices in this course helped you reduce stress or anxiety?

- How has our work in mindfulness, meditation, or contemplative practices in this course helped you become more purposeful, motivated or focused in your life or academic goals?

- How has our work in mindfulness, meditation, or contemplative practices in this course helped you provided you with better methods to work productively with others?

Conclusions

UDL goals and processes intersect naturally with mindfulness and contemplative activities in class. Multiple means of engagement and experiential interactions provided students with creative, social, and cognitive avenues to express their learning with mindfulness in the class. Students surveyed about their learning in the class provided encouraging feedback on their experiences. Students found that through mindfulness activities they worked more productively with others. They generally felt that their efforts with mindfulness help them become more resourceful and knowledgeable and able to maintain a purposeful, motivated, goal-focused life. Stress reduction and self-acceptance were also noticeable achievements for dedicated students.

Through an effort in daily mindfulness activities and weekly reflective journals students in engaged in dialog, art, self-reflection, self-discipline, and initiated essential coping strategies. It should be reiterated that the grading process is not used as a method for judging whether or not student correctly practiced mindfulness. A non-judgmental position is foundational to both students and teachers practicing mindfulness. When practicing a method of personal inquiry encouraging and acknowledging insights and connection are more valuable feedback than grades or corrections. This creates a safe space for students with all manner of learning abilities, yet balances of accountability with flexibility. Feedback on journals are not corrective, instead it simply affirmed insights or encouraged and further introspection through prompts that sought rich and vivid descriptions of the personal practice. Students are prompted to write about both insights and resistance to the mindfulness experiences.

Mindfulness in the context of an academic course can be framed as a cognitive mode of experiential inquiry but will enviably edge into social-emotional domains of learning. Teachers will need to be prepared to create environments and resources that support and facilitate exploring vulnerabilities and uncharted interior landscapes in their students. Creating a sense of trust, openness, and community prior embarking on extended work with mindfulness is well advised. Additionally, teachers considering implementing mindfulness practices will benefit from first solidifying their own experiences with mindfulness.

Mindfulness can be framed as a self-development skill, a method of first-person inquiry, a leadership skill, or process to enhance self – awareness, reduce stress, and help students be more resourceful, as well as work productively with others. Although this case study provides indirect assessment of UDL outcomes through students’ self –reflections, their responses indicate promising results for integrating mindfulness to support UDL goals.

Learn More

On Mindfulness and Leadership

Finding the Space to Lead: A Practical Guide to Mindful Leadership (2015) Janice Marturano

On Mindfulness and Teaching

Teaching Mindfulness: A Practical Guide for Clinicians and Educators (2010) Donald McCown, Diane K. Reibel, Marc S. Micozzi

Mindfulness for the Next Generation: Helping Emerging Adults Manage Stress and Lead Healthier Lives 1st Edition Holly Rogers and Margaret Maytan (2012)

Teaching Mindfulness in Schools: Stories and Exercises for All Ages and Abilities (2017) Penny Moon

The Mindful Education Workbook: Lessons for Teaching Mindfulness to Students (2016)Daniel Rechtschaffen

Appendix A

Student Responses to End of Semester Reflection Questions

The following captures the anonymous, verbatim responses of the students final reflections based on the questions that align with specific aspects of UDL outcomes.

- How has our work in mindfulness, meditation, or contemplative practices in this course helped you gain self-awareness?Student A – It begin with the instruction to pay attention to attention. My attention. I had never in my adulthood taken time just to be with myself without worry, anxiety, and doubt accompanying. During this time I discovered layers to myself. I realized that I am more than my anxiety. I am strong and I am okay with the unknown. Most of the time.Student B – I can understand if I am stressed or not and I know how to relax.Student C – Mindfulness has and will continue to guide myself and lead me to learn about myself. Contemplation has made me stop and learn more about myself more than any other concept.Student D – Yes.Student E – I have greater understanding of communication and being mindful of how my words might affect a situation. I’ve become more confident in my words within the classroom setting.Student F – The journaling definitely was great, through awareness and reflection it translated nicely into daily self-awareness. My favorite thing for this was the door handle practice. I already practice self-awareness through many paths, such as walking barefoot everywhere… awareness through walking.

Student G – It showed me that I was not as self-aware as I previously thought mainly because I was trying to avoid it. This class helped me by making me face the things I did not want to face.

Student H – more introspective – mindful speaking – pausing before reacting – understanding people don’t always act/say things that are mindful.

Student I – Working on a personal practice made me work on self exploration and helped me understand why I am the way I am.

- How has our work in mindfulness, meditation, or contemplative practices in this course helped you become more resourceful or knowledgeable?Student A –I have learned that I have a lot of the answers in myself already. I’ve also learned to trust myself and my instincts.Student B – YesStudent C – I am more resourceful in many ways. I know more about myself now than I ever did. I have so much more knowledge about myself that I can lead and trust even better than before. I have gained knowledge from my other classmates as well!Student D –Yes I believe so.Student E – I gained understanding in how to access the resources available to me when I needed them. I feel that I have gained a more universal perspective understanding.Student F –This has helped me research plants – my love 🙂 The step back and taking- a – moment breath is useful. This is helpful for interacting with others.

Student G – It lead to the realization that I have actual morals that I’ve already got working and that I want to work on.

Student H – I gained a better sense of self-identity b/c I lost the dependence on conformity and others acceptance.

Student I – I learned my strengths, and have learned to work with them.

- How has our work in mindfulness, meditation, or contemplative practices in this course helped you reduce stress or anxiety?Student A – I have learned that when I have a panic attack, nature can be a resource. Meditating takes time and not always easy to start, but once I begin I fall into moments of effortlessness.Student B –I have ways to reduce my stressStudent C – In my experience my stress has went down immensely. Breathing exercises were probably the most helpful practice. Forcing myself to sit and observe my own breathing patterns was very helpful.Student D – I feel more in control of my life and less stressed because of it.Student E – Deep Breaths and awareness helps me to release anxiety. This is so important.Student F –Journaling was a stress point, but the short period in the grateful journal where we did not have to write, but kept it in mind, was calming and a meditation more my speed.

Student G – N/A

Student H –I developed a few anxiety reducing practices like relaxing my muscles. I also had to confront my fear of presenting.

Student I – Greatly! I have made more progress with reducing anxiety and monitoring my bipolar disorder than I have in a year of therapy.

- How has our work in mindfulness, meditation, or contemplative practices in this course helped you become more purposeful, motivated or focused in your life or academic goals?Student A – When I can’t focus on my work, I can step outside, take a few breaths, phone free. This recharges me. Before my practice, I didn’t know it could.Student B – Meditate = Relax = FocusStudent C – I have learned that it is okay to focus on myself.Student D – I am more in controlStudent E – I have accepted that I have a variety of interest and have the ability to access these all and intermediate them.Student F – Well… it is a personal transformative class, so in being that, it has been useful in making me more purposeful.

Student G – N/A

Student H – [blank]

Student I –I have been able to do things faster, and by extension get more done.

- How has our work in mindfulness, meditation, or contemplative practices in this course helped you provided you with better methods to work productively with others?Student A – I’ve become a more active listener. I’ve lost the need to talk the most or be right. I have re-learned to enjoy listening to others and their stories.Student B – The more relaxed I am, the better I work with others, The more I practice mindfulness the more relaxed I am.Student C – Understanding to delegate, suspend judgment, to ask for help if you need it.Student D – Totally! I am a better communicator because of this classStudent E – I’ve been more open to share in class and face the reality of my responsibilities.Student F – Mindful speaking is the Best : ) If there are any other practices for them please teach it!

Student G – It helped me realize that I should be less judgmental of myself and others, which helped me be more compassionate when dealing with others. That ends up creating a more productive space.

Student H – I am able to work better with people because my open body language makes others comfortable.

Student I – Over the course of the semester, our practice of open dialogue has helped me become friends with a former enemy.

References & Resources

Abell, M. M., Jung, E., & Taylor, M. (2011). Students’ perceptions of classroom

instructional environments in the context of ‘universal design for learning’. Learning Environments Research, 14(2), 171-185

Altobello, R. (2007). Concentration and contemplation. A lesson in learning to learn. Journal of Transformative Education, 5, pp. 354-371.

Bach, D. J., & Alexander, J. (2015). Contemplative approaches to reading and writing: Cultivating choice, connectedness, and wholeheartedness in the critical humanities. The Journal of Contemplative Inquiry, 2(1), 17-36. Retrieved from http://journal.contemplativeinquiry.org/index.php/joci/article/view/41

Barbezat, D. & Bush, M. (2014). Contemplative practices in higher education, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.Berkeley CA: North Atlantic Books.

Berila, B. (2014). Contemplating the effects of oppression: Integrating Mindfulness into diversity classrooms. Journal of Contemplative Inquiry 1:55 -69.

Bogels, S., Hoogstad, B., van Dun, L., de Schutter, S., & Restifo, K. (2008). Mindfulness training for adolescents with externalizing disorders and their parents. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36(2), 193–209. doi: CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Brady, R. (2007). Learning to stop, stopping to learn. Journal of Transformative Education 5 (4), pp. 1- 25.

Brown, R. (2011). Inner to outer: The development of contemplative pedagogy. J.

Simmer-Brown & S. Grace (Eds.) Meditation in the classroom. Albany NY: SUNY Press.

Brown, R. (2014). Transitions: Teaching from the spaces between. In O. Gunnlaugson,

E. Sarath, C. Scott & H. Bai (Eds.) Contemplative learning and inquiry across disciplines. Albany NY: SUNY Press, pp. 271-286.

Burgstahler, S. E., & Cory, R. C. (2008). Universal design in higher education: From principles to practice Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Burrows, L. (2015). Inner alchemy: Transforming dilemmas in education through mindfulness. Journal of Transformative Education, 13, 127–139.

Bush, M. (2010). Contemplative higher education in contemporary America. Amherst, MA: Centre for Contemplative Mind in Society. Google Scholar

Byrnes, K. (2012). A portrait of contemplative teaching: Embracing wholeness. Journal of Transformative Education, 10, 22–41. Google Scholar, Link

Caldwell, K., Harrison, M., Adams, M., Quin, R. H., & Greeson, J. (2010). Developing mindfulness in college students through movement-based courses: Effects on self-regulatory self-efficacy, mood, stress, and sleep quality. Journal of American College Health, 58(5), 433-442. doi: 10.1080/07448480903540481

CAST (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Cast.org http://www.cast.org/our-work/about-udl.html

Chickering, A. W., Dalton, J. C., & Stamm, L. (2015). Encouraging Authenticity and Spirituality in Higher Education. Hoboken: Wiley.

David, D. S. (2009). Mindful teaching and teaching mindfulness: A guide for anyone who teaches anything. Somerville: Wisdom Publications.

Dencev, H., Collister, R. (2010). Authentic ways of knowing, authentic ways of being: Nurturing a professional community of learning and praxis. Journal of Transformative Education, 8, 178–196.

Edyburn, D. L. (2010). Would you recognize universal design for learning if you saw it? Ten propositions for new directions for the second decade of UDL. Learning Disability Quarterly, 33(1), 33-41.

Edelstein, A. (2017). The conscious classroom: The inner strength system for transforming the teenage mind. Philadelphia: Emergence Education Press.

Fink, D. (2018) A Self-Directed Guide to Designing Courses for Significant Learning (pdf) Retrieved 2/16/2018 from: https://www.deefinkandassociates.com/GuidetoCourseDesignAug05.pdf

Gallagher, W. (2010) Rapt: Attention and the focused life. New York: Penguin.

Gray, E. (2004) Conscious choices: A model for self-directed learning. Upper Saddle River: Pearson.

Greeson, J. M., Juberg, M. K., Maytan, M., James, K., & Rogers, H. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of Koru: a mindfulness program for college students and other emerging adults. Journal of American College Health, 62(4), 222-233. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2014.887571

Grossenbacher, P. & Rossi, A. (2014). A contemplative approach to teaching observation skills. Journal of Contemplative Inquiry, 1, pp. 23-34.

Gunnlaugson, O. E. Sarath, C. Scott & H. Bai (Eds.) Contemplative learning and inquiry across disciplines. Albany NY: SUNY Press.

Gunnlaugson, O. (2007). Shedding light on the underlying forms of transformative learning theory: Introducing three distinct categories of consciousness. Journal of Transformative Education, 5, 134–151.

Gunnlaugson, O. (2011). Advancing a second-person contemplative approach for collective wisdom and leadership development [Electronic journal article]. Journal of Transformative Education, 9, 3–20

Hart, T. (2004). Opening the contemplative mind in the classroom. Journal of Transformative Education, 2, pp. 28-46.

Hart, T. (2008). Interiority and education: Exploring the neurophenomenology of contemplation and its potential role in learning. Journal of Transformative Education, 6, 235–250.

Huston, D. (2010). Communicating mindfully: Mindfulness-based communication and emotional intelligence. Madison OH: Cengage Learning.

Jennings, P. (2015). Mindfulness for teachers: Simple skills for peace and productivity in the classroom. New York, NY: Norton.

Kaparo, R. (2012). Awakening somatic intelligence: The art and practice of embodied mindfulness. Berkeley CA: North Atlantic Books.

Levy, D. (2016). Mindful tech: How to bring balance to our digital lives. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Mak, C., Whittingham, K., Cunnington, R. et al. Efficacy of Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Attention and Executive Function in Children and Adolescents—a Systematic Review. Mindfulness (2018) 9: 59. https://doi-org.proxy006.nclive.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0770-6

McGuire, J. M., Scott, S. S., & Shaw, S. F. (2006). Universal design and its applications in educational environments. Remedial and Special Education, 27(3), 166-175.

Miller, J. (2010). Whole child education. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

Miller, J. (2014). The contemplative practitioner: Meditation in education and the workplace. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press through their “ground of being” experiences. Journal of Transformative Education, 10, 42–60. Google Scholar, Link

Nation Center On Universal Design for Learninghttp://www.udlcenter.org

O’Reily, M.A. (1998). Radical presence: Teaching as contemplative practice. Portsmouth NH: Heinemann.

Owen-Smith, P. (2018). The Contemplative Mind in the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning,Indiana University Press

Palmer, A., & Rodger, S. (2009). Mindfulness, stress, and coping among university students. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 43(3), 198-212. Retrieved from http://0-search.proquest.com.wncln.wncln.org/docview/195804643/fulltext/3B4B90AC6B3C4B9EPQ/1?accountid=8337

Palmer, P. J. (2004). A hidden wholeness: The journey towards the undivided self. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Palmer, P. J. (2007). The courage to teach:Exploring the inner landscape of a teachers life. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Robinson, P. (2004). Meditation: It’s role in transformative learning and in the fostering of an integrative vision for higher education. Journal of Transformative Education, 2, 107–119.

Rose, D. H., & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development Retrieved from https://login.proxy006.nclive.org/login?url=https://search.proquest.com/docview/62194652?accountid=8337

Sable, D. (2014). Reason in the service of the heart: The impacts of contemplative practices on critical thinking. The Journal of Contemplative Inquiry, 1(1), 1-21. Retrieved from http://journal.contemplativeinquiry.org/index.php/joci/article/view/2

Scharmer, O., Senge, P., Jaworski, J., Flowers, B. (2004). Presence: Human purpose and the field of the future. Society for Organizational Learning. Cambridge, MA: Society for Organizational Learning.

Schultz, K. (2010). After the blackbird whistles: Listening to silence in classrooms. Teachers College Record 112 (11) pp. 2833-2849.

Shafir, R. (2003). The Zen of listening: Mindful communication in the age of distraction. Wheaton IL: Quest Books.

Shapiro, S. L., Brown, K. W., & Astin, J. (2011). Toward the integration of meditation into higher education: A review of research evidence. Teachers College Record, 133(3), 493-528.

Thich Nhat Hahn (2013). The art of communication. New York: Harper One.

Zajonc, A. (2006). Cognitive and affective relationships in teaching and learning: The relationship between love and knowledge. Journal of Cognitive Affective Learning 3 (10), Pp. 1-9.

Zajonc, A. (2009) Meditation as contemplative inquiry. Great Barrington MA: Lyndisfarne.

About the Author

Elaine Gray

Dr. Elaine Gray is the ePortfolio Director at Appalachian State University. She teaches a First Year Seminar class entitled “The Art of Attention” and a course on “Contemplative Leadership and Personal Transformation” in Watauga Residential College. She is a founding member of the faculty and staff organization Still Point that is dedicated to contemplative inquiry and practice and she leads a faculty/staff learning community that focuses on contemplative pedagogy. Elaine earned her Masters degree in Liberal Studies at Rollins College. She holds a Ph.D. in Integral Studies from the California Institute of Integral Studies and is currently working towards completion of her Ed.D in the Educational Leadership doctoral program at Appalachian State University. Her publications include the textbook Conscious Choices: a Guide to Self-directed Learning (Pearson, 2004).