Service Learning Success

Contents

Introduction

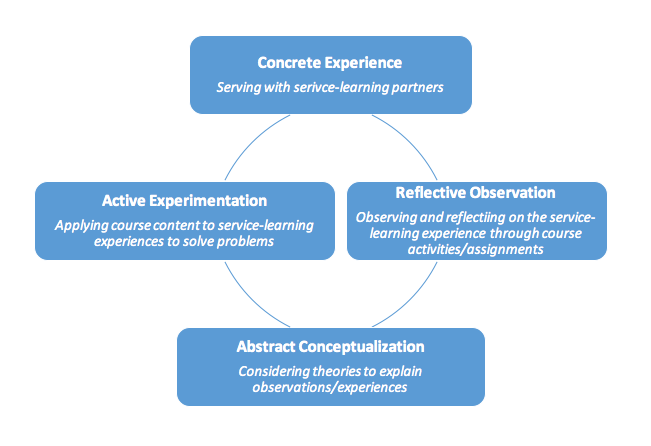

Rarely can the world’s problems be adequately grasped within the four walls of a classroom. Service-learning is a pedagogical technique that combines experiential learning practices with community engagement and encourages personal growth through reflection in the classroom. Service-learning is not exclusive to student benefits: universities and colleges can increase community engagement and develop mutually beneficial relationships through this practice. Service-learning within a course is designed in a way so that the course objectives, tasks, and assignments align with student service projects that meet community needs. In this process, students engage in concrete experiences with thoughtful reflection to promote abstract conceptualization and create connections with course material. Students then utilize the knowledge gained in class with their service-learning sites through active experimentation.

UDL Alignment

Service-learning naturally is not a “one-size-fits-all” process. Each student’s learning experience is different and highly customizable based on the needs of the student and the service-learning partner.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression

Courses can be structured in sync with the service-learning experience to allow students to navigate the learning environment in a way that works best for them. Course activities should also be structured so that students are able to share what they have learned using different modes of expression. These avenues are only limited by the imagination of the student and instructor. Traditionally, students reflect through written essays, course discussions, and perhaps a presentation or report at the end of the program. Reflection prompts can be delivered to students via multiple avenues with the most common being in-class discussions and writing prompts. Online prompts can also be used, as well as discussion boards which are popular on course management systems. Prompts are structured in a step-wise process to help guide student reflection throughout the service-learning process.

However, with the addition of novel technology, the opportunities for expression are nearly limitless. Students can post photos and/or comments for discussion in Google+ communities, utilize other social media outlets, author blog posts, participate on discussion boards, and create presentations (Atre, Belotti, McMahon, Morris, & Gaszak, 2018). Photos from peers may be stronger catalysts for discussion that text prompts alone. Multiple means of action and expression are easily housed within a service learning experience, supporting the UDL principles.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Engagement

Students are encouraged, if not required, to set their own parameters for their service-learning experience. Students may be provided individual choice through ranking their service-learning site preferences or working with their service-learning partners to determine what activities they will be engaging in. Students are able to determine the timing for the hour completion to accommodate their schedules. Naturally, service-learning is immediately relevant and valuable, as the experiences directly involve the community. This being the case, students are also exposed to new threats and distractions, which can be minimized through a longstanding authentic relationship between service-learning partners and the instructor. Maintaining this genuine relationship can also help to provide a means for communication if the student is not meeting expectations early within the experience.

Students are encouraged to utilize previous knowledge from other courses in the ideal service-learning program as service-learning partners and instructors agree upon mutual program goals (Michigan State University, 2015). For example, within my Community Nutrition course students are also challenged to complete activities that use their nutrition knowledge from previous courses such as nutrition education seminars or cooking demonstrations.

Service-learning activities should be connected to course learning activities. When these various learning activities progress in a sequential manner, this can be a way to provide a step-wise guide to help increase student comprehension. The instructor in a service-learning based course can provide checkpoints for hour attainment and communication goals for service-learning partner/student interaction. The instructor can set course deadlines related to the service-learning experience. For example, a student can be required to meet with their service-learning partner (electronically, over the phone, or in person) by a certain date and/or attain at least X hours by a certain date.

Service-learning emphasizes placing students in real-world scenarios where problems cannot be isolated into one discipline. Students must use previous knowledge and learning experiences to piece together the world around them. Effectively, students are able to take abstract concepts learned in the course and apply them directly to real-world scenarios.

Finally, the fundamental constructs of service-learning: engagement and reflection align perfectly with the goal to provide multiple means of engagement, one of the key UDL principles. Service-learning provides creative means to expand university-community partnerships through purposeful service and deep self-reflection by students.

Instructional Practice

Basic Overview

Service-learning is a form of experiential pedagogy that combines service through meeting community-identified needs, and learning through application of course concepts and intentional critical self-reflection (Cashman & Seifer, 2008; Jacoby, 1996; Office of Community Engagement and Partnerships & University of South Florida, 2018). Service-learning is unlike mere service hours as it is dependent upon the critical reflection component as well as continuous input from the community (Furco, 1996). Further, the purpose of service-learning is to provide a real-world application for course concepts to give students context for material learned in class. This pedagogical practice is perfectly aligned with the goal of UDL: to create learners who are purposeful, motivated, resourceful, knowledgeable, strategic, and goal-oriented.

The structure of service-learning is based on Kolb’s experiential learning model. This model illustrates a successful experiential learning process as having four major components: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation (Kolb, 1984). As shown in Figure 1, the key components of the experiential learning model are manifested in the service-learning experience. Service-learning is distinctly unique from mere service hours as course material is aligned with experiences so students are able to apply course content to their service-learning sites to solve real-world problems (Akella, 2010; Bringle & Hatcher, 1996; Petkus, 2000).

Figure 1: Kolb’s experiential learning model in the context of a service-learning experience

Key Benefits

The most cited benefits of service-learning are those for student learning outcomes and evidence suggests that students prefer service-learning courses over their traditional lecture-based courses (J. S. Eyler, Giles, Stenson, & Gray, 2001; Stavrianeas, 2008). Students benefit from service-learning through a multitude of ways, including critical thinking skills through the ability to apply course content to real-world situations (Jenkins & Sheehey, 2011; Vogelgesang & Astin, 2000). Furthermore, service-learning can be a tool to develop writing skills and improve academic performance (Astin, Vogelgesang, Ikeda, & Yee, 2000). Service-learning has been shown to impart these benefits for students of all backgrounds (Mungo, 2017).

Soft skill development is yet another benefit from service-learning (Cooke, Ash, Nietfeld, Fogleman, & Goodell, 2015; Heiss, Goldberg, Weddig, & Brady, 2012; Pierce, Havens, Poehlitz, & Ferris, 2012; Piper, DeYoung, & Lamsam, 2000). Soft skills include experience, team skills, communication skills, leadership, problem-solving, self-management, and professionalism skills (Crawford, Lang, Fink, Dalton, & Fielitz, 2011). Students have also reported increased awareness of the needs of others in addition to an increased desire to serve (Mann & Misyak, 2018; Piper et al., 2000). Students are not simply crossing physical barriers, where they are required to go forth into the community, but they cross and internal border which makes these inequalities more evident (Bailey, 2017). Cultural awareness is another benefit for service-learning that is not directly tied to course material. Previous work has found that students gain cultural awareness through the service-learning experience (Chang, 2002).

Benefits of service-learning are not merely limited to the student experience (Driscoll, Holland, Gelmon, & Kerrigan, 1996). Universities naturally have many resources that can help strengthen the bonds between universities and community organizations. These resources include programming, personnel, expertise, and academic materials. Community organizations and individual members have noted advantages to service-learning including increased community involvement, students as catalysts for inspiration, community learning, and the positive impact students can have on the community (Gerstenblatt, 2014).

Limitations

While there are many demonstrated benefits from service-learning, service-learning is not the universal solution to all academic woes. Students of all backgrounds can benefit from service-learning yet these benefits have not been shown to improve graduation rates in underrepresented populations (Song, 2017). Further research is needed to fully understand how the service-learning process impacts students, and the role instructors can play to can make the experience more accessible to all students. While properly executed service-learning provides multiple ways to engage in course content, the principles of UDL must be taken into consideration when designing the learning experience. By keeping these UDL principles in mind, avoiding unintentional barriers to learning will be more straightforward.

Getting Started

Starting with Service-Learning: Critical Key Elements

Service-learning, when utilized in a course, will need a few critical elements to maximize student and community benefits. When designing a course with a service-learning component or developing a service-learning program it is important to include the following (Jenkins & Sheehey, 2011; Office of Community Engagement and Partnerships & University of South Florida, 2018):

- Community Connections: Continued and genuine relationships with service-learning partners

- Course Structure: Course material applicable to service experience, meaningful goals and objectives for the service-learning project

- Assessment and Demonstration: Opportunities for critical reflection and celebration of the experience

Community Connections

A successful service-learning program is built on meaningful community partnerships. These service-learning partners will assist students to apply course material to real-world situations and maintain consistent contact with the course instructor. It is imperative that service-learning partners agree that the experience is both service and an opportunity for students to utilize and exercise course concepts. For example, with the Community Nutrition course, local food banks offer opportunities for students to exercise nutrition education skills. To begin making connections with potential service-learning partners, examine existing university/college connections that already are established. Networking with faculty and staff can also help create connections. Nonprofits can also be wonderful service-learning partners. Many universities also have outreach or service institutes that can assist with identifying potential partners.

During the initial process, it is important to have identified learning goals for students, understand partner/organization goals, establish the service-learning partners as educators, and to maintain communication (Michigan State University, 2015). Further, key points to consider for successful service-learning partnerships include being attentive to the service-learning partner’s mission, being mindful of the partner’s resources: material and human, sharing responsibility for shortcomings, considering longevity of the partnership, and understanding process as important for a long-standing partnership (Tinkler, Tinkler, & Strouse, 2014). Utilizing a community-based participatory research approach where community members determine research questions and approaches to tackle these questions is an essential way to tackle service-learning, as both institutional and community parties will benefit (Stoecker, Loving, Reddy, & Bollig, 2010).

Service-learning success is highly dependent on relational experiences with consistent communication (Gerstenblatt, 2014). Practically, it is important to identify what students would be doing for their service-learning at that site, the number of students needed and expected outcomes from the partnership (Kaye, 2004). I have found it helpful to also inform students of typical service-learning site hours, so they can adequately prepare.

To facilitate communication with service-learning partners, it may be necessary to develop many different forms of contact and pinpointing the best method of communication desired by the service-learning partner. Service-learning partners should be aware of the expectations for the course and take a vested interest in the course/program. Service-learning partners should be invited to verbalize any difficulties that may arise. This can be done throughout the experience as direct contact with the instructor and/or through more formal evaluations. Some partners may feel more comfortable relaying the difficulties they had in a more formal format such as through evaluation forms. These evaluations should offer opportunities to give feedback on both the students and the experience as a whole. Some suggestions questions include what is/is not working well, what changes are needed, what expectations have/have not been met, and sources of frustration/satisfaction (Michigan State University, 2015).

Course Structure

Syllabi should include relevant information for both the course and the service-learning component of the course. Expectations of the experience should be made clear, as well as course components bearing credit that are associated with service-learning. Students need to know how much time is expected for their service-learning commitment 15 hours/semester recommended) and the guidelines for course assignments such as reflective journals and/or other service-learning related projects (Mabry, 1998). Students should be able to access the evaluation tool used by partners to judge the quality of their effort over the course.

Students may choose, rank or be assigned to a service-learning site to serve with if the course is affiliated with multiple partners. Giving students choice over their project can increase interest and resulting quality of student experience (Werner & McVaugh, 2000). Community partner information should be made available or easily accessible to students including the organization name, mission statement, and contact information. Other information that is often useful for students includes a service-learning partner schedule, special event times and days, preferred methods of communication, description of activities, and location. Anecdotally, I have also found it very helpful to include whether or not the service-learning site is accessible from campus by public transportation, especially for students who do not have access to a vehicle.

It is imperative to have course assignments that align with the service-learning experience such as over-arching service-learning based projects, reflective assessments, service-learning partner completed evaluations, hour completion, and the final presentation/demonstration based on the service-learning tasks at the termination of the course.

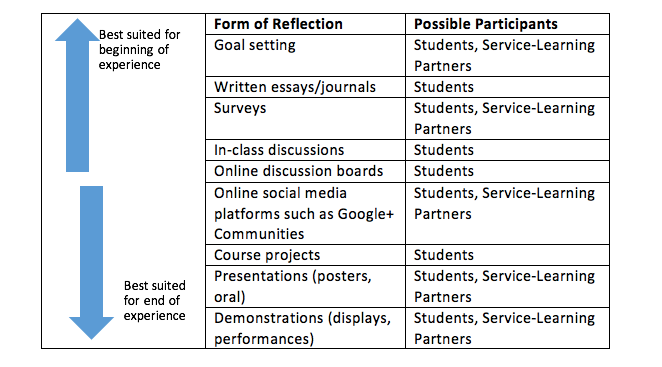

Assessment and Demonstration

Assessment in the service-learning coursework fosters student reflection and can be a useful tool for program evaluation. These reflections should include both formative and summative feedback opportunities (Mabry, 1998; Misyak, Culhane, McConnell, & Serrano, 2016). Reflective pieces should be introduced before the service-learning experience, during the experience, and after the experience. Reflection can be introduced to students in many forms, of which the most common are writing and presentations (Bringle & Hatcher, 1996). However, instructors are not limited to these forms. Suggestions posed by Eyler include elements of reflection with others and alone, and gives suggestions for what topics/forms may be the most important to consider depending on the timing of the reflection (J. Eyler, 2002). For instance, students may set service-learning goals before the experience, write reflections, participate in course discussions during the experience, and present to their community partner at the end of the experience. Each of these activities involves different participants at different points of the service-learning process. There are benefits and trade-offs for students working in teams to complete reflective activities, so it may be beneficial to incorporate a combination of individual and group reflective exercises (K. Lambright & Lu, 2009). By providing many forms of reflection, the UDL principle of multiple means of action and expression is kept. Students are able to express their experiences through multiple forms of creation, documentation, and collaboration with peers and/or service-learning partners. This provides a flexible format for students to demonstrate their findings and experiences in a way that may be more appropriate for them. Additionally, using multiple means of action and expression allows for a more natural representation of how students will demonstrate knowledge in the workplace post-graduation. Figure 2 shows several options, though not an exhaustive list, of possible exercises for reflection and demonstration.

Figure 2: Suggestions for reflective activities in a service-learning course (Atre et al., 2018; J. Eyler, 2002; Jenkins & Sheehey, 2011; Office of Community Engagement and Partnerships & University of South Florida, 2018)

Celebration activities, often in the form of presentations or sharing sessions, are a great place to infuse multiple means of action and expression, and can be wonderful to help student learning success. Presentations and/or demonstrations are opportunities for students to share what they learned and show off the hard work they achieved throughout the semester. This can be through simple discussions of things they have learned or presentations of course projects related to the service-learning experience. Having partner support is also important in the demonstration step. Further, each student engages with their service-learning experience in a different way, another UDL principle: multiple means of engagement. This can be shared with peers to create a diverse learning environment and provide additional opportunities for feedback.

Evaluating Service-Learning in the Classroom

Evaluation is another key element to ensure the efficacy of a service-learning program. There are many factors that can alter the outcomes of the service-learning program. Using reflective activities or adding surveys into the course are great ways to keep track of how the program is progressing. There are a variety of methods to evaluate the course and can range from a minimal time commitment to intensive, depending on the depth of feedback desired. Some suggestions for evaluating service-learning during the course include in-class mini quizzes using response technology, class discussions, reflective writing, course projects that parallel student experiences with service-learning sites, and evaluation forms completed by service-learning partners (Misyak et al., 2016). After course completion, both students and service-learning partners can provide more in-depth feedback through surveys, interviews, and focus groups (Holland, 2001; Jones, 2010). It is important to keep the needs of service-learning partners in mind when evaluating the course, as their needs drive service-learning activities.

Within the course structure, factors that might affect the efficacy of a program include the type of reflective activities, how the service-learning program is integrated into the curriculum, quality and degree of instructor guidance provided, and time/contact with the service-learning partners (K. Lambright & Lu, 2009). Student characteristics that may be important to measure are gender, race, and previous work/volunteer experience (K. Lambright & Lu, 2009). Anecdotally, I have also found that the number of hours students are completing at the time of the experience can heavily influence their experience as well. Service-learning site types or formats might also be of influence on the experience and could affect student outcomes (Mann & Misyak, 2018).

Troubleshooting

While service-learning is a pedagogical practice with many benefits for the university, community, instructor, and student it is a time-intensive strategy that requires patience and much work before the course begins.

Liability

First, to ensure that the institution is adequately covered legally, students should sign waivers and receive clarification on University policies around working with minors. Most institutions will provide these forms through outreach or community engagement offices. Be sure to check with your University to determine what policies are in place for community work. For example, the University of Mississippi provides a student service learning guideline and release form available for use by faculty (McLean Institute for Public Service and Community Engagement, 2015). It may also be necessary to have students sign a photo release to allow for pictures of their experiences to be shared on university websites or local newspapers (Michigan State University, 2015). Photo waiver templates are often available through service-learning toolkits referenced in the “learn more” section here. It is important to emphasize to students that any photos they take must always have the subject’s consent first and be taken in good will. Before the service-learning experience, I find it helpful to provide students with a list of expectations which includes being physically and mentally present at their service-learning sites. This provides students with a guide to adhere to, as well as written documentation of the expectations for the course.

Travel Needs

Students living on campus may have limited or inadequate access to transportation to facilitate a service-learning experience. I have found the best way to navigate this issue is to provide service-learning partners that are accessible from campus either on foot or off the bus route. Students are asked if they have access to a car when they select service-learning partners. I prioritize placing students without transportation in sites that are more accessible to them.

Other Challenges

Some students may face additional challenges unique to them. In the case of students experiencing social anxiety, learning difficulties, or physical disabilities it is imperative to keep lines of communication open. Be open with the student, ask them how they view the process and make yourself available to help mitigate issues. Careful relationships with service-learning partners can ensure positive student experiences help to carefully navigate these challenges that may arise. For example, students with physical disabilities may work better with service-learning partners that are on campus and easy to access. Students with social anxieties may work better with service-learning partners that are in the planning phases of projects. I have found that there is a fit for all students, it just takes some time on the instructor and student’s behalf to find that fit. Again, it is so important to be accessible to students so they feel comfortable expressing any possible barriers they may face for a successful experience. I find it helpful to make learning students’ names a priority, and encourage them to see me during office hours, even if it is only to chat. I try to maintain a professional yet informal atmosphere so that students feel comfortable asking questions and raising concerns. It is also important to know what your scope is as a professor, and feel comfortable referring students to on-campus support such as the counseling center and career center if needed. Prior to establishing the program be sure to know what the on-campus resources are and how to direct your students to them.

Disciplines

Many different fields of study can effectively utilize the service-learning pedagogy to engage students and maximize learning outcomes. Service-learning has been used in various fields and the table below shows some articles relevant for each field but is not an exhaustive list. Service-learning is also not limited to undergraduates. It can also be effectively used in a graduate curriculum.

| Communication | Ahlfeldt, S. L. (2009). Thoughtful and informed citizens: An approach to service-learning for the communication classroom. Communication Teacher, 23(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/17404620802581851 |

| Ecology | Reynolds, J. A., & Lowman, M. D. (2013). Promoting ecoliteracy through research service-learning and citizen science. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 11(10), 565–566. https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295-11.10.565 |

| Economics | Paxton, J. (2015). A practical guide to incorporating service learning into development economics classes. International Review of Economics Education, 18, 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iree.2015.01.001 |

| Marketing | Petkus, E. (2000). A theoretical and practical framework for service-learning in marketing: Kolb’s experiential learning cycle. Journal of Marketing Education, 22(1), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475300221008 |

| Medical field | Gimpel, N., Kindratt, T., Dawson, A., & Pagels, P. (2018). Community action research track: Community-based participatory research and service-learning experiences for medical students. Perspectives on Medical Education, 7, 139–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-017-0397-2 |

| Nursing | Bassi, S. (2011). Undergraduate nursing students’ perceptions of service-learning through a school-based community project. Nursing Education Perspectives, 32(3), 162–167. |

| Nutrition | Misyak, S., Culhane, J., McConnell, K., & Serrano, E. (2016). Assessment for learning: Integration of assessment in a nutrition course with a service-learning component. NACTA Journal, 60(4), 358. |

| Pharmacy | Nemire, R. E., Margulis, L., & Frenzel-Shepherd, E. (2004). Prescription for a healthy service-learning course: A focus on the partnership. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 68(1), 28. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj680128 |

| Social work | Deck, S. M., Platt, P. A., & McCord, L. (2016). Engaged teaching-learning: Outcome evaluation for social work students in a graduate-level service learning research course. Advances in Social Work, 16(2), 233. https://doi.org/10.18060/18302 |

| Teacher education | Bates, A., & Lin, M. (2015). Service-learning and teacher education. New Waves—Educational Research & Development, 18(1), 3–4. |

Summary

While service-learning is a sometimes time-consuming and complex pedagogy practice, the benefits extend beyond those of student gains in knowledge. It requires a commitment to the community and students alike. However, once established the service-learning course component can be an effective avenue to strengthen university-community ties, utilize university resources, and engage students in the community. Further, it can be a highly customizable avenue to provide accessible education to students with diverse learning profiles.

Learn More

Learn More: Guides and Toolkits

Center for Community Engagement and Service Learning. (2018). Faculty service-learning resources. Retrieved from https://www.hws.edu/academics/service/faculty_resources.aspx

Center for Service-Learning and Civic Engagement, Michigan State University. (2015). Service-learning toolkit: A guide for MSU faculty and instructors. Retrieved from https://servicelearning.msu.edu/upload/Service-Learning-Toolkit.pdf

Office of Community Engagement and Partnerships, University of South Florida. (2018). Service-learning toolkit. Retrieved from https://www.usf.edu/engagement/faculty/service-learning-toolkit.aspx

Vanderbilt University. (2011). What is service learning or community engagement? Retrieved from https://wp0.vanderbilt.edu/cft/guides-sub-pages/teaching-through-community-engagement/

References & Resources

Akella, D. (2010). Learning together: Kolb’s experiential theory and its application. Journal of Management & Organization, 16(1), 100–112. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.16.1.100

Astin, A. W., Vogelgesang, L. J., Ikeda, E. K., & Yee, J. A. (2000). How Service Learning Affects Students. Los Angeles, CA: Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA.

Atre, S., Belotti, D., McMahon, M., Morris, R., & Gaszak, P. (2018, February). An effective tool for shared experience approach to student learning, community building and classroom teaching. Oral Presentation presented at the Conference on Higher Education Pedagogy, The Inn at Virginia Tech and Skelton Conference Center Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Virginia. Retrieved from https://chep.cider.vt.edu/content/dam/chep_cider_vt_edu/CHEP_2018_Proceedings_Final.pdf

Bailey, M. S. (2017). Why ‘where’ matters: Exploring the role of space in service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.3998/mjcsloa.3239521.0024.104

Bringle, R. G., & Hatcher, J. A. (1996). Implementing service learning in higher education. The Journal of Higher Education, 67(2), 221–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.1996.11780257

Cashman, S. B., & Seifer, S. D. (2008). Service-learning: An integral part of undergraduate public health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(3), 273–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.012

Chang, M. J. (2002). The impact of an undergraduate diversity course requirement on students’ racial views and attitudes. The Journal of General Education, 51(1), 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1353/jge.2002.0002

Cooke, N. K., Ash, S. L., Nietfeld, J. L., Fogleman, A. D., & Goodell, L. S. (2015). Impact of a service-learning-based community nutrition course on students’ nutrition teaching self-efficacy. NACTA Journal, 59(1), 28.

Crawford, P., Lang, S., Fink, W., Dalton, R., & Fielitz, L. (2011). Comparative Analysis of Soft Skills: What is Important for New Graduates? Retrieved from http://www.aplu.org/members/commissions/food-environment-and-renewable-resources/CFERR_Library/comparative-analysis-of-soft-skills-what-is-important-for-new-graduates

Driscoll, A., Holland, B., Gelmon, S., & Kerrigan, S. (1996). An assessment model for service-learning: Comprehensive case studies of impact on faculty, students, community and institution. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, (3), 66–71.

Eyler, J. (2002). Reflection: Linking service and learning-linking students and communities. Journal of Social Issues, 58(3), 517–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00274

Eyler, J. S., Giles, D. E., Stenson, C. M., & Gray, C. J. (2001). At a glance: What we know about the effects of service-learning on college students, faculty, institutions and communities, 1993- 2000. In Higher Education (3rd ed.). Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/slcehighered/139

Furco, A. (1996). Service-learning: A balanced approach to experiential education. In Expanding Boundaries: Serving and Learning (pp. 2–6). Washington, DC: Corporation for National Service. Retrieved from http://www.shsu.edu/academics/cce/documents/Service_Learning_Balanced_Approach_To_Experimental_Education.pdf

Gerstenblatt, P. (2014). Community as agency: Community partner experiences with service learning, 7(2), 22.

Heiss, C. J., Goldberg, L. R., Weddig, J., & Brady, H. (2012). Service-Learning in dietetics courses: A benefit to the community and an opportunity for students to gain dietetics-related experience. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 112(10), 1524–1527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2012.07.028

Holland, B. A. (2001). A comprehensive model for assessing service-learning and community-university partnerships. New Directions for Higher Education, 2001(114), 51. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.13.abs

Jacoby, B. (1996). Service-learning in higher education: Concepts and practices. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Jenkins, A., & Sheehey, P. (2011). A checklist for implementing service-learning in higher education. Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship, 4(2), 52.

Jones, S. R. (2010). The unheard voices: Community organizations and service learning. The Journal of Higher Education, 81(6), 715–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2010.11779080

Kaye, B. (2004). The complete guide to service learning: Proven, practical ways to engage students in civic responsibility, academic curriculum, and social action. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit Publishing Inc.

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Lambright, K., & Lu, Y. (2009). What impacts the learning in service learning? An examination of project structure and student characteristics. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 15(4), 425–444.

Mabry, J. (1998). Pedagogical variations in service-learning and student outcomes: How time, contact and reflection matter. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 5, 32–47.

Mann, G., & Misyak, S. (2018, February). Service-learning in a community nutrition course: Influence of site on student perceptions. Presented at the 10th Annual Conference on Higher Education Pedagogy, Blacksburg, VA. Retrieved from https://chep.cider.vt.edu/content/dam/chep_cider_vt_edu/CHEP_2018_Proceedings_Final.pdf

McLean Institute for Public Service and Community Engagement. (2015). Student service-learning guidelines and release. Retrieved September 21, 2018, from http://mclean.olemiss.edu/files/2014/05/Student-Service-Learning-Guidelines-Release.pdf

Michigan State University. (2015, October). Service-learning toolkit. Retrieved August 23, 2018, from https://servicelearning.msu.edu/upload/Service-Learning-Toolkit.pdf

Misyak, S., Culhane, J., McConnell, K., & Serrano, E. (2016). Assessment for learning: Integration of assessment in a nutrition course with a service-learning component. NACTA Journal, 60(4), 358.

Mungo, M. H. (2017). Closing the gap: Can service-learning enhance retention, graduation, and gpas of students of color? Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 23(2). https://doi.org/10.3998/mjcsloa.3239521.0023.203

Office of Community Engagement and Partnerships, & University of South Florida. (2018). Service-learning toolkit. Retrieved August 24, 2018, from https://www.usf.edu/engagement/faculty/service-learning-toolkit.aspx#Anchor1

Petkus, E. (2000). A theoretical and practical framework for service-learning in marketing: Kolb’s experiential learning cycle. Journal of Marketing Education, 22(1), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475300221008

Pierce, M., Havens, E., Poehlitz, M., & Ferris, A. (2012). Evaluation of a community nutrition service-learning program: Changes to student leadership and cultural competence. NACTA Journal, 56(3), 10–16.

Piper, B., DeYoung, M., & Lamsam, G. (2000). Student perceptions of a service-learning experience. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 64(2), 159.

Song, W. (2017). Examining the relationship between service-learning participation and the educational success of underrepresented students. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.3998/mjcsloa.3239521.0024.103

Stavrianeas, S. (2008). Students prefer service learning over traditional lecture in a nutrition course. The FASEB Journal, 22(1S), 683.1-683.1. https://doi.org/10.1096/fasebj.22.1_supplement.683.1

Stoecker, R., Loving, K., Reddy, M., & Bollig, N. (2010). Can community-based research guide service learning? Journal of Community Practice, 18(2–3), 280–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705422.2010.485878

Tinkler, A., Tinkler, B., & Strouse, G. T. (2014). Key elements of effective service-learning partnerships from the perspective of community partners. A Journal of Service-Learning & Civic Engagement, 5(2), 16.

Vogelgesang, L. J., & Astin, A. W. (2000). Comparing the effects of community service and service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 7, 25–34.

Werner, C., & McVaugh, N. (2000). Service learning rules that encourage or discourage long term service: Implications for practice and research. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 7, 117–125.

About the Author

Georgianna Mann

Dr. Georgianna Mann is an assistant professor in the Department of Nutrition and Hospitality Management at the University of Mississippi. Originally tracked to attend veterinary school at the University of Georgia, her career path changed after becoming a teaching assistant for a study abroad program to Australia. After completing her Masters of Science in Food Science and Technology, she also received her Doctorate of Philosophy at Virginia Tech after shifting to behavioral nutrition in the Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise. Her current research is grounded in community nutrition.

Dr. Mann engages in experiential pedagogical practices of which service-learning is one. She is the current instructor for Community Nutrition as well as Experimental Foods, which is a multidisciplinary course designed to give students interprofessional experience through hands-on product development and testing.