Simple Tools and Debriefing Help Achieve Learning Outcomes

Contents

Introduction

This Case Study will teach facilitators how to use low-barrier, low-resource instructional tools such as children’s puzzles to achieve targeted learning outcomes which are realized through a facilitated debriefing process. We explain and explore how to use puzzles in multiple ways as an activity, that when followed by a facilitated debrief, aids learners in translating and transferring the experience to their own lives, and in some cases, professional disciplines. These debriefs can be mapped against external competency and skill domains, as well as Bloom’s Taxonomy for learning. Additionally, they are consistent with principles of Universal Design for Learning by providing responsive learning opportunities geared to participants’ understanding, adapted to any audience.

There are many low-barrier, low-resource instructional tools to engage learners in skill-building for collaborative teamwork. Through the use of children’s puzzles, which are completed by putting like contours of the pieces together (as in a jigsaw puzzle) we demonstrate how to utilize a single, inexpensive resource to provide team-based experiences in multiple ways while debriefing them to target different learning objectives. The techniques can be used by teachers/facilitators in face-to-face classroom or training environments and can be readily adapted as well to both synchronous and asynchronous teams in online teaching environments. The tasks themselves require no prior experience or training for participants, thus leveling opportunities for success among learners.

While we use these in graduate-level health professions education, we have had similar successes with high school students as well as professionals in their respective fields of expertise. We believe these activities are relevant to other fields and disciplines, as well, such as when teaching group negotiation processes in a business course or communication skills within any field. Ultimately, skills learned through this module are easily applicable to other, similar activities to broaden opportunities for student engagement in learning, and several additional low-barrier, low-resource ideas are included in this discussion. The reader takes away an understanding of the model and process for using these tools and should be able to apply easily attainable, inexpensive resources at hand to immediately implement this approach.

Objectives

As a result of participating in this module, the participant will:

- Differentiate between tasks that are naive in structure and those that require previous knowledge and skill, and compose learning activities that focus on naive tasks.

- Construct and experiment with the formation of appropriate debriefing questions that promote learner reflection on challenges and successes in the learning activity.

- Support learners through guided debriefing to permit them to transfer learning to other experiences.

UDL Alignment

Providing students with multiple means of engagement

Our students are preparing to participate in team-based environments. While we provide an emphasis on interprofessional healthcare teams, we find that our methods also provide non-clinical participants with valuable insights (7.2). Students select how they engage with their teammates, and at what intensity (8.2, 8.3). Should a student choose to take more an observer than an active player, they still gain insights into team function through the interactions of others (7.1, 9.3).

Providing opportunities for multiple means of representation

We design multiple games from a single resource to target varied learning objectives. The use of puzzles is a single way to teach a number of important team science concepts; many of the same concepts can be taught with other low-resource tools given that the learning is not in the activity itself, but in the debriefing that follows. The facilitator reinforces concepts and innovates their style of teaching to target their audience (3.3). Our online resources mimic classroom activities, allowing students who are not collocated to share a similar learning experience. During the debriefing portion of learning, results are discussed in both small and large groups, and insights are recorded on whiteboards for reference by learners in subsequent activities (1.1). This time allows us to talk about the language and the importance of using a common language as a foundation for all learners (2.1, 2.4).

Providing options for multiple means of action and expression

Games allow diverse learners to simultaneously experience interactions on teams, creating a common experience from which to reflect and respond, regardless of previous team experience, educational level, or even given differences in communication and learning (4.1). Games are active and dynamic, and they can be made progressively more difficult, thereby increasing the cognitive load (5.2, 5.3). During the debriefing, students reflect on their experiences, drawing conclusions that include the reflections of their teammates. Learners speak about their experiences without the risk of being “wrong” as each encounter is as unique as the person who participated in it. Students reflect about what they have observed, possibilities they might have wished for, their emotional connection to what occurred, etc. and are invited to translate what they have learned to situations of relevance to them (6.3, 6.4).

Instructional Practice

The use of naive tasks to teach complex lessons may at first seem counter-intuitive. Naive tasks are those in which the learner requires little or no prior knowledge and are not able to increase their likelihood of success in the task through coursework or study. When considering learner variability, this can eliminate many barriers that are created by inconsistency in background knowledge or experience and is consistent with the UDL principle of providing multiple means of representation. Simple children’s games, designed for maximum participation by participants with minimal ability, knowledge, or skill (and again consistent with UDL principles related to stimulating interest and motivation among learners) become an ideal format for teaching such complex issues as team science (the interactions of team members, how teams are formulated, issues of communication and leadership, etc.) Additionally, as we discuss later in this case study, the activities can be easily transferred to other disciplines. The reality is that the tasks themselves do not teach new skills, but transfer the information to relevant disciplines, courses of study, etc. The new knowledge/skills are attained through the use of broad metaphors, which are manifested during debriefs. For example, asking about the challenges that may have occurred on a team which was functioning together for the first time in a naive task may metaphorically point to those faced by teams who have not yet discussed roles and responsibilities, task completion, communication expectations, etc. Thus, the use of tasks becomes very flexible– one activity can be used to teach a wide variety of issues based on the facilitator/teacher directing the debrief toward specific learning objectives.

These realizations are typically recognized during the reflective question period either integrated into the activity or following its completion. This process is called debriefing and is most often carried on by a trained facilitator who has observed the students during the activity. Accomplished teams may learn to debrief themselves over time. Debriefing is a process of asking open-ended questions that are intended to provoke reflection about the experience, not to quiz for specific answers. In essence, a debrief provides meaning and relevance for learners, allowing them to connect the naive task to their own experiences, often through metaphors. Metaphors are intentionally identified in the design of both the activity and the debriefing. Broad metaphors would be those that have application across a wide variety of circumstances, disciplines, etc. Narrow metaphors, by contrast, are more limited, illuminating a more precise band of skills, information, etc., and often are discipline specific.

Debriefing as a technique is used throughout this case study and deserves some clarification. A debrief is a facilitated conversation most often led by the instructor, in which questions posed to the learner(s) engage reflective thinking to provide meaning to the task just completed. As such, they become a valuable UDL tool where the questions follow the learner, meaning that new questions are responsive to answers given to previous ones. This adaptive format for instruction requires not only that the learner be engaged, but that the facilitator/instructor is, as well. In our experience, debriefs can be done with learners remaining in their seats, often with the most recently completed challenge still in front of them. That allows them to be reminded of the experience and, if needed, to reference particular parts of the task as they create their reflections and responses. A skilled facilitator will have been observant of the process and may ask questions specific to what has been noted about how the task was approached, what was successful, what wasn’t, frustrated or enthused responses, etc. Consistent with UDL, the debrief is designed to optimize learning for the individual or group. It also provides yet another opportunity for engagement and action/expression on behalf of the learner.

Debriefs can be as long or as short as is both practical and where learners remain engaged. We utilize a two-tier system, in which initial questions are targeted to lower critical thinking skills (such as in Bloom’s Knowledge and Comprehension.) For some groups, this is sufficient. We drill deeper, however, in the second tier, in which questions are shaped more by reflection aligned with application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. It is in this line of questioning that learners are asked to more deeply translate and transfer the experiences of the naïve tasks and simple tools to their own disciplines and the instructor’s learning objectives. For that reason, rich discussions may last much longer than a first tier discussion. Typically, our debriefs have lasted from five minutes to forty-five minutes. It is worth mentioning that we believe skilled facilitators can always test out the success in meeting learning objectives by the participants’ responses to questions asked. In other words, while it is important to follow the learning exhibited by participants, one can direct the conversation to some extent by the questions one poses. That being said, however, if learners do not respond in ways that indicate they have achieved the learning objective, perhaps the simple truth is that they haven’t. In that instance, the instructor must reevaluate both the objectives and the tasks.

In the resource section of this case study, the tool “Team Debriefing Utilizing TeamSTEPPS® Concepts and Bloom’s Taxonomy” is an example of two-tier debriefing from a very specific set of learning objectives. It outlines the two-tier approach and identifies potential questions and the application of Bloom’s taxonomy to serve as a guide for facilitators.

Once again, the instructor remains attentive to the process and responses and may make decisions about learner engagement that will dictate the overall length. Instructors may steer the conversations to specific learning tasks but are wise to also listen to and respond to what learners seem ready and able to engage. Questions may be broadly targeted or may be too specific groups if there are multiple teams. Rarely do we ask specific questions to one student, although once a student has provided a response, we may follow up with questions that probe into what they have offered. We always offer, however, that individual students are not put on the spot for answers to what happened, opening opportunities for others to share in the reflection. The process of the debrief opens possibilities that students can express what they know in different ways, consistent with the UDL principle of multiple means of action and expression.

Debriefing begins with a question inquiring about what went well. This launches the reflection on a positive note and avoids any concerns for members of teams that did not complete the task that there is some sort of blame being pursued. Although the facilitator/teacher should be prepared with some specific inquiries, following the pathways of learning that are articulated by the students in their responses can lead to some powerful outcomes. As a facilitator, paying attention to what learners noticed in the exercise and what they articulate allows the conversation to have a natural flow, building logically from one topic to another. Debriefing questions can be structured such that they elevate the learning by inquiring about qualities of the experience above and beyond the activity itself. Ultimately, a good debriefing spotlights the metaphors present that are translated into specific disciplines. The leadership of this experience must be prepared to ask questions that help draw correlations between the activity and the learning objectives.

The use of broad metaphors allows the teacher/facilitator to apply these same techniques to a variety of disciplines. Putting together a children’s puzzle as a team, for example, could be used to provoke a conversation about the interactions of characters in an English writing assignment, the interdependency of events to provide an historical context, an understanding of the diversity of factors affecting a local or national economy, the need for a flight crew to work together to assure passenger safety, or the elements of a business plan to optimize work in a factory. Ultimately, the task is of less importance, and the learning event itself is defined largely by the ability of the facilitator to utilize the metaphor to teach. Above and beyond the diversity of topics that lend themselves to these activities, we will later discuss the elevation of cognitive loads in simple tasks to also reach across layers of professional development and the levels of sophistication of the learning objectives as well as the learner. There is a relationship between the degree to which the task in the activity is naive and the likelihood of the metaphor being broad. The simpler the task, the more likely it is to have a diversity of applications. The more focused or more difficult the task (relying more specifically on knowledge or skills), the narrower the metaphor is likely to be.

As an example of how these naive tasks might be used, in the interest of being both low-resource and low-barrier (providing information and content in different ways and stimulating interest and motivation for learning, consistent with UDL principles) for these lessons, this approach will discuss using a single tool (children’s contour puzzles) in four different, interdependent methods to teach concepts. They are an example of a broad metaphor. The children’s puzzles to which we refer are generally from a dollar discount store. The most common kind we utilize is a 24-piece puzzle that does not have an outside frame (a so-called jigsaw puzzle) often with images of the characters familiar to young children through storybooks, movies, or public media. We find it helpful to have a variety of images while retaining similar formats (numbers of pieces, shapes of finished puzzles, etc.) Because of the very low cost of the resource itself, we have amassed enough puzzles for our learning environment that teams of participants may work from several different kinds of puzzles for the sake of variety, elevating the cognitive load, such as in the third and fourth activity examples in this case study.

There are some simple caveats in using puzzles. First, if teams do not complete the assembly task in the allotted time, do not be surprised if they continue to work to solve the puzzle even when you are trying to debrief the project. It seems that it is hard to keep one’s hands off an uncompleted puzzle! Second, pay attention to whether or not all of the pieces to complete the puzzle have been provided to the learner(s) (although the fourth example intentionally does not.) It is easiest just to have the puzzle pieces counted periodically in each container. If it is a 24 piece puzzle, but you have 23 pieces in one bag and 25 in another, it narrows down the likelihood of the solution. Third, and finally, instruct your participants that the puzzles should not be forced together, thus bending or tearing important shapes on the puzzle piece. To eliminate breaks in the engagement and interest of learners, our team collects puzzles from an activity being debriefed by a facilitator and often distributes a new puzzle to each team during that time.

Below you will find four variations on the theme of using these puzzles along with some suggested debrief questions that draw from the metaphors each activity represents:

Puzzles: Image Down

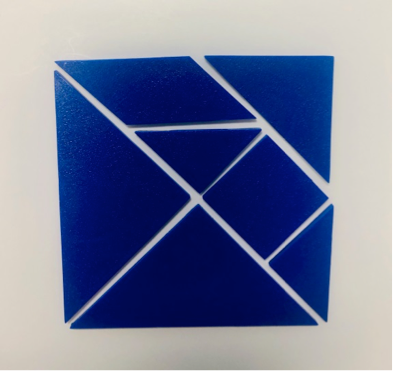

Figure 1: Puzzles image down

In the first exercise, teams of four to seven students are provided a twenty-four piece child’s puzzle. Ideally, we have them already placed on the table with the image face down but have found it equally workable to provide the puzzle pieces in a small plastic storage bag and have the participants place the pieces face down as they remove them from the package. The task is simple: complete the puzzle in as little time as possible leaving the image face down. Events such as this are timed to create a sense of urgency but are intentionally not structured to be competitive. In other words, the directions are very specific: in as little time as possible. They are working against the clock, not against other teams. (To be honest, we don’t draw that distinction for teams at this point. That means many participants are assuming that they are in competition with neighboring teams, which may increase their focus and engagement.) Do not be surprised if team members struggle to complete this task or appeared frustrated. The task itself appears to be simple; however, in the absence of being able to see the image, key information that supports the task completion is not available. While the assumption may be that anyone ought to be able to do the task quickly, it is actually more challenging for some individuals and teams than it may first appear due to the absence of visual clues one would experience if the image were present.

When one or more teams have completed the task or when a reasonable time has expired (i.e., 3-4min), the experience is debriefed. Debriefing questions targeted for a team development activity might include:

- What worked well for you and your team in accomplishing the task of assembling the puzzle?

- How was this experience different for you than other puzzles you have completed in the past? What strategies did you and your team use to complete the task?

- How did your team self-organize? Did a clear leader emerge from your team? If so, how was that leader chosen?

- What was the effect of working with the puzzle with the image face down on the table? How did it impact (if at all) your ability to complete the task in a timely manner?

- If having the puzzle image face down limited the information about relationships between the pieces and made assembly of the puzzle more difficult, how does limited information about other team members or their roles and responsibilities potentially impact how a team functions? How might a team adapt when the information they need is not available?

Utilizing the debrief format to draw the learner toward other objectives is also possible, however. These examples provide limited depth to the topics indicated, but are examples of how to direct learners toward other disciplines:

- How do the pieces of a puzzle fitting together seem similar or different to you as you think about the design of the plot in your story? In writing, is it necessary to have all the elements of your plot clearly laid out before writing the story? (English or creative writing course)

- If you were to place meaningful names on these puzzle pieces from your understanding of concepts in economics, how would you name them, particularly as they interlock with or relate to one another? (Economics)

- When considering the intricacies of sound in Beethoven’s 5th symphony, how might assembling this puzzle reflect the challenges faced by the composer, the conductor, or a performer in this musical piece? (Music theory, music performance)

- What relationships can you name in the human digestive tract that would mimic the interlocking pieces of this puzzle? How might you use a puzzle such as this to demonstrate these concepts to your patient/client/person? (Science, anatomy, health care)

- In losing the visual cues to complete this task, explain how you might feel if you were an unsighted person working in your current job or location? Are there strategies that you think might be helpful to mitigate this impact? (Diversity and inclusion)

Hopefully, these questions suggest to facilitators how they guide open-ended discussions toward established learning objectives. A debrief of the activity will help shape the meaning and purpose of the activity for learners.

Puzzles: Image Up

Figure 2: Puzzle with image up

This variation on puzzles can be done either as a stand-alone lesson or can be coupled with the puzzle activity described above. The difference between the activity as a stand-alone or as a part of a larger lesson is made apparent by the debrief questions that will be asked.

We have found it very effective to have teams work on a different puzzle with each iteration of activities, so we simply switch puzzles around from team to team for each activity. One of the easiest methods we have found is the use of a sealable sandwich bag as packaging for each puzzle, asking teams to place the pieces of their completed puzzle (now unassembled) back into the bag. The facilitator can easily move puzzles from one station to another or can ask learners to pass their puzzles to the next station in a sequence, such as clockwise.

In this activity, similar to the one described above, teams are instructed to assemble the puzzle as quickly as they can. This time the puzzle is assembled with the image side facing up. Once again, a limited time is provided, creating an urgency to get the task completed.

When one or more teams have completed their puzzles, or when a reasonable amount of time has passed (i.e., 2-3min), the activity is debriefed. Below are examples of debriefing questions related to collaborative teams. We have broken them out into the two categories of 1) connecting this second puzzle activity to the first, or 2) using this puzzle activity as a stand-alone lesson.

Using this activity in concert with the first, some debriefing questions might include:

- What went well? What differences did you notice between your team and how it functioned this time compared to the last puzzle?

- What are the reasons one might find the assembly of the puzzle easier with the image visible versus when the image was hidden? Given that the image-up puzzle provides more information to connect contiguous (adjoining) pieces, in what ways might it illustrate the need for team members to know the roles and responsibilities of others?

- How necessary was it to know what the full image would be when the puzzle was completed? Once you identified what the image was, how did it affect your approach to and ability to solve the entire puzzle? How might that affect leadership on the team? What is the relationship of knowing the full image in a puzzle and sharing a common vision for teams?

Using this activity as a stand-alone, some debriefing questions might include:

- What went well in this activity?

- How did your team organize itself to accomplish the task? Did you discuss a strategy prior to beginning the puzzle? Did a single leader emerge? How was that person chosen or affirmed by others?

- In this activity, you had several people working with the same information attempting to complete the same task simultaneously. In your team, did individuals hang onto single pieces of the puzzle, or did members work with the puzzle pieces all together? What difference would it have made if selected pieces of this puzzle had “belonged to” an individual such that nobody else could touch them?

- What similarities or differences do you see in a team collaboratively completing a puzzle and a situation in which individuals with unique expertise work together to complete a task?

Again, utilizing the debrief format to draw the learner toward other objectives is also possible. These examples provide limited depth to the topics indicated, but are examples of how to direct learners toward other disciplines:

- How might the smaller details in your story make clear or obscure for the reader how the plot fits together in a coherent way? What is the responsibility of the author to make transparent particular plot themes to the reader, and how important is it for that to happen early in the story? What are the advantages or disadvantages of this process being iterative throughout the story? (English, creative writing)

- It seems that small pieces of information can either positively or negatively affect an economy of any scale. Using the puzzle as a metaphor, explain to your client the impact of his/her sharing all aspects of personal finances with a financial planner. How is that similar to or different from the issues of transparency for consumers in a larger economic system? Should, for example, consumers be provided all of the information discussed at meetings of the Federal Reserve in the setting of interest rates? (Economics)

- Conductors are given the score for a musical piece that permits them to see the entire composition. Individual players, however, are given sheet music that outlines only their (or a very limited number of others’) responsibilities as a performer in the piece. In what ways is knowing the expected image of a puzzle when one has access only to individual pieces at the beginning similar to or different from the notes given to the conductor? To the performers?

- The complexities of the human body are such that it is not only how pieces fit together (like contours in a puzzle) but also how they function together and influence one another. Using the puzzle as an example of the interrelatedness of body parts and pieces, explain the influence of visual details of the total image that you could see in each puzzle piece on how you put the puzzle together. Following that, explain your theory for how subtle differences, such as stress, pain, inflammation, etc. in parts of the body may affect the body as a whole. How might that influence your diagnostic abilities? (Science, anatomy, health care)

- How might becoming focused on the image being created in this puzzle have impacted negatively on your abilities to see how pieces fit together? How aware were you of the contours that needed to align, versus what you expected images in the puzzle to look like? Are there advantages to having people with different skills or different abilities on your team when working on a task? Why? (Diversity and inclusion)

At the end of this activity, have teams replace their disassembled puzzle in the sealable bag and return it to the facilitator.

Puzzles: Modified

Figure 3: This puzzle has been modified using a sharp blade to remove pieces such as tabs and edges. Here one can see how contours that might normally appear to go together do not seem to. The usual cues are gone. Normally done as a face-up puzzle to make it easier, expect this activity to frustrate some learners as it defies expectations they have set. To elevate the cognitive load, use a non-rectangular puzzle, such as an oval, a bow tie shape, etc.

This activity is distinguished from the first two in that it requires modification of puzzle pieces and utilizes puzzle shapes that increase the cognitive load for participants. It can be used either in the sequence of puzzle exercises (with a suggested order of image-down, image-up, and then modified puzzles.) It can also be used with either the first or the second activity without doing the entire sequence.

Using a sharp cutting tool (we used an X-Acto knife) trim away edges of approximately ⅓ to ½ of the puzzle pieces, leaving the puzzle looking as normal as possible. One might take simply an edge off or may choose to remove entire sections of the puzzle piece, including tab connectors that would normally hold the puzzle together. The intention here is to create a puzzle that even when it is complete will have holes and missing edges upon completion. The changes in the puzzle pieces will challenge assumptions and strategies learners used in earlier challenges. If possible, work with puzzles that are different from the ones used earlier. For example, if the 24-piece puzzle(s) end up being rectangular in shape (which they often do, running four pieces by six pieces) select puzzles for this exercise that are not rectangular and modify them as described above. The challenge will be to those teams that have strategized to complete the puzzle by, for example, assembling the straight edges as a starting point. That strategy (due to both the modification and the design of the puzzle) may be less effective. Additionally, the inability of puzzle pieces to connect to one another will compel the learners to challenge their own assumptions and expectations, and potentially to proceed in the project without the growing assurance of success. Puzzle pieces that originally would clearly have fit together now don’t and their modifications may cause participants to think that they do not have the piece correctly placed in the puzzle. All of this is to elevate the cognitive load of this activity– that is, to increase the level of and amount of critical thinking, having the team operate in an environment of increased adversity.

When one or more teams have completed their puzzles, or when a reasonable amount of time (i.e., 4-5min) has passed, the activity is debriefed. As in earlier examples, these debriefing questions could be related to collaborative teams.

- What went well in this activity for you and your team? How did this puzzle compare to previous ones?

- What assumptions were challenged as you attempted to complete this puzzle? What biases did you form about our puzzle activities that may have worked against your success?

- During this activity, when did you and your team realize that pieces of this puzzle did not fit together in the same manner as previous puzzles? What do the gaps in the puzzle represent to you, particularly in the ways in which this puzzle may reflect the work you are doing? (Connect the metaphor to your work.)

- How did your team respond when confronted with possible conflicts generated by individuals realizing the nature of this puzzle earlier in the activity, versus those who struggled to understand as the activity progressed?

As was demonstrated earlier, utilizing the debrief format to draw the learner toward other objectives is also possible. These examples provide limited depth to the topics indicated, but are examples of how to direct learners toward other disciplines:

- In written compositions, ideas may be introduced that are never fully developed. These ideas may be abandoned, leaving holes that the reader may continue to wonder about. What is the place in writing stories or other compositions for introducing ideas, but then leaving them undeveloped? How might that benefit the reader? (English, English composition)

- What is the acceptable level of failure (such as might be represented by the holes in this puzzle) when working with large-scale economic systems? Does the type of failure, the timing of the failure, or the scope of the failure matter? Contrast your thoughts with what might happen in a small-scale or micro-economic system. (Economics)

- In representing a musical composition visually, one might suggest periods when the orchestra makes no sounds (such as extended rests) by the holes in this puzzle. Compare and contrast the effect of the holes in your puzzle with those you might hear in Beethoven’s 5th symphony. You may not have the same type of response to the holes in the puzzle as you do to silence in a symphony. Share and explain your reflection about the role of silence in musical compositions. (Music theory, music performance)

- In your puzzle, there were unexpected gaps in visual information, represented by the holes in the image. How did your team respond in identifying those gaps, and what was your strategy for continuing to solve the puzzle? How might a healthcare provider respond if a patient fails to disclose all of the medications being taken (because they forget them, they don’t consider them to be medicine, etc.) in a form on patient history? How much tolerance do you think is reasonable for incomplete records, histories, etc. related to patient care? How might we still be able to see the whole person if they have “holes” (i.e., are missing vital organs or limbs)? (Science, healthcare)

- One of the challenges in this puzzle is that the frequency or amount of on-going assurances or successes was interrupted by pieces that were incomplete or did not fit together in ways we are used to. How might that impact a team member who has completed a task previously, but who now is not witnessing typical milestones in a project? How might you support a team member whose own needs in this regard are different from you or other team members? (Diversity and inclusion)

Puzzles: Collaboration across the system

In this example, facilitators must mix pieces of puzzles in advance of the activity. It is suggested that two or more pieces from each puzzle be removed and placed with puzzle pieces from another puzzle. Replacement pieces may be from a single puzzle, or you may wish to elevate the cognitive challenge by mixing them up. The more pieces you remove from a puzzle and replace with pieces from other puzzles, the more complex this activity will feel.

Each team is given a puzzle, which they are to complete as quickly as possible. The image can be face up (although, again, to elevate the game, you can try this face down. The concern here is that the task will become too frustrating given that one will match puzzle pieces across the system with only the contour shape as the guide.)

Teams will come to the realization that they do not have the correct puzzle pieces to complete the puzzle if they keep their team efforts in isolation. Watch for examples when team members cross over to other teams, noting whether they have come offering pieces, seeking to trade pieces, etc. Also, pay attention to how that information may affect the entire group as the awareness moves from team to team.

At one point, indicate that the only way any single team can “win” is if everyone in the room completes their puzzle, as well. In other words, nobody “wins” unless everybody “wins.” Make a mental note of any changes in behavior from players once that new rule is announced. This challenge may be elevated depending on whether you simply mixed pieces among the puzzles being put together by the teams, or whether your extra pieced also came from an additional puzzle that none of the teams started with. Those pieces, even after the team puzzles are done, will still need to be assembled, even though no team is identified as being responsible for them.

The activity is over once all puzzles have been completed.

As in earlier examples, these debriefing questions could be related to collaborative teams.

What went well? How did your team respond when it realized it lacked all of the pieces needed to complete the project? What strategy did your team use to get the correct pieces?

How would you describe the relationship of teams within a single system? How is that like or unlike the relationship of individuals within a single team?

When most of our systems are built on a system of competition, what is it like to work collaboratively? How do you feel about working as hard to make certain someone else succeeds as you do to attain your own success?

What do you think happens when people or teams within a system become fearful for their own outcomes? How could fear sabotage collaboration?

Utilizing the debrief format to draw the learner toward other objectives is also possible. These examples provide limited depth to the topics indicated, but are examples of how to direct learners toward other disciplines:

How often do you utilize peer groups to provide you with feedback for your writing? What is the agreement you have with them regarding critiques/feedback? What is the value when authors are supportive of one another rather than critical? (English, English composition)

Collaboration seems counter-intuitive to the way in which most economic systems in the Western Hemisphere work. Describe possible outcomes for using collaborative rather than competitive strategies in business. Do you think it would improve or be detrimental to quality? (Economics)

For musical compositions to work correctly, musicians must be willing to express their work collaboratively. Sometimes they must be quieter, allowing other sections to be highlighted. Other times, they must assert the presence of their instruments boldly. What are the challenges in an orchestra or band to maintaining that collaborative spirit, particularly when musicians are being cut due to financial constraints? (Music theory, music performance)

The human body has been described as a system of systems. What happens when systems become unbalanced? In what way does the human serve as a living metaphor for the need for collaborative effort? (Science, healthcare)

In this exercise, you were met with the challenge of needing to collaborate outside of your team in order for your team to complete its task, and to support other teams in theirs. On teams, we sometimes meet people who really don’t fit into the task that we are trying to complete due to different personalities or a skills-mismatch. How would it feel to realize that the team to which you are assigned doesn’t want you, doesn’t need you, or can’t fit in whatever you have brought to the table? How can systems help align workers with appropriate tasks? (Diversity and inclusion)

Ultimately, simple tools can potentially teach a lot to learners. With children’s contour puzzles as an example, it is not hard to imagine the diversity of lessons that could be taught by using other simple, naive tasks to generate metaphors for learning. How, for example, could a ping pong ball, a plastic spoon, and a plastic cup teach lessons about mutual support, situation monitoring, or even communication? In what ways can simple bandanas teach learners about trust, trust-building, and communication?

Some similar naive tasks that have proven popular with our learners in teaching teams and teamwork include:

Figure 4: Teamwork exercise with ping pong ball

- Short pieces (12”-15”) of wooden corner molding held with the concave side up to serve as a track for a ping pong ball. One piece is given to each participant, who functions as part of a team. The team must create a pathway for the ping pong ball to travel to end up in a cup a short distance away. The ball must pass over the length of each team member’s track at least once on its way to the destination. When the ball in is a player’s track, they must remain standing still; they may not walk with the ball in their piece of track. Other players organize (on a rotating a basis as the ball is passed from player to player, moving into position when they are not holding the ball) with the team working toward the common goal. If the ball is dropped by any player, it is returned to the starting point. To elevate the challenge, 1) do not permit talking, and/or 2) once a team has begun to achieve success, start a second ball down the track before the first one is fully placed.

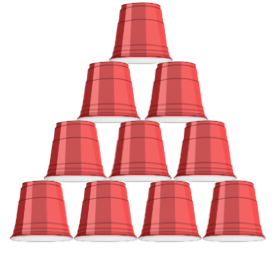

Figure 5: Tangram Puzzle

- Tangram puzzles are seven geometric, non-curvilinear shapes (called tans) that fit together to make a square. The puzzle is reported to have its origin in Chinese culture and is available from a variety of sources. We were able to find them from a well-known online seller for approximately $1.00 each, and have been very satisfied with their durability. We provide one set of puzzle pieces per team. Beyond the square, they can also be used to create a variety of shapes and designs representing people, animals, objects, etc. The challenges can be found in abundance either online or in print, and range from easier to harder. Teams work together to complete the puzzle challenge, which is represented to them as a solid, completed shape, not showing how the puzzle pieces are configured. Similar to other activities described in this case study, debriefing about teams and team functioning, but also around a variety of disciplines, is possible. You can elevate the challenge by 1) prohibiting talking, or 2) placing enough pieces in the center of the table for a team so that each person must complete the puzzle at their own station, taking only one piece at a time from the center. In this version, we call out part way through the activity that nobody wins unless all puzzles have been completed, which moves the activity away from competition and compels collaboration.

Figure 6: Rubber band with strings attached

Figure 6: Cups stacked in a pyramid

- Create devices made from a simple rubber band to which are attached 4-6 pieces of string (of 36”-60” in length,) distributed relatively equally around the outside of the rubber band. When team members hold onto the outer ends of the strings, they should be creating tension in the rubber band so that it stretches. Using 6-10 cups (such as drinking cups, with plastic being more durable), teams must create a pyramid shape of stacked cups by using the device to lift them into position. (With six cups, you will have three on the bottom row, two on the second row, and one cup on top. With ten cups, you will start with four cups on the bottom row, followed by the configuration described above.) Team members may not touch the cups directly. It will be easier if the cups have been placed upside down on the table, with the opening facing down, making the outside tapered end available to the team. Team members must work together to move cups into place. This activity can provide some good insights into team communication, situation monitoring, mutual support, and leadership. To elevate the challenge, 1) team members must hold onto the string using touching only the two inches on the end furthest from the elastic. They may not guide the string with their free hand, and they must keep their strings taut at all times. The longer the string, the greater the challenge. 2) Constrain communication, such as having the team work in silence or allow only designated people to speak (essentially as designated leaders.) 3) Blindfold a few of the team members so that they cannot see.

When teachers/instructors/trainers/facilitators can move beyond the rigidity of a model that requires expensive resources, they may not only broaden the tools with which they teach, but they may open up accessibility to learners based on the simplicity and familiarity of the tools with which they work and the tasks required for participation. Naive tasks remove the barriers to learning that are also associated with concerns about risk and consequence. Not being able to complete a puzzle as a team does not reflect on one’s professional career, but it may indeed be used to teach about key issues that will benefit the participant now or in the future.

Learn More

- https://serc.carleton.edu/introgeo/games/index.html

- https://hbr.org/2015/07/debriefing-a-simple-tool-to-help-your-team-tackle-tough-problems

- https://www.um.edu.mt/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/351760/Reflectivedebriefing.pdf

- https://rfu.ms/smartgames

References & Resources

Burke, B. (2014). Gamify: how gamification motivates people to do extraordinary things. Boston: Bibliomotion.

Gray, D., Brown, S., & Macanufo, J. (2010). Gamestorming: a playbook for innovators, rulebreakers, and changemakers. Beijing: OReilly.

Michalko, M. (2006). Thinkertoys a handbook of creative-thinking design. Berkeley: Ten Speed Press

Nilson, C. (1998). Games that drive change. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Voss, T. (2018). Transform your training: the Metalog method. Norderstedt, Germany: Books on Demand.

About the Author

Bill Gordon

Dr. Bill Gordon is a faculty member at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science. With an undergraduate degree in arts education and two advanced degrees in ministry and spirituality, he brings a divergent perspective to health sciences education. Charged with teaching about teams and collaboration, he helps create educational opportunities for students, staff, and faculty through the use of games and engaged learning.

Lori Thuente

Dr. Lori Thuente, PhD, RN, is the Director for the Center for Interprofessional Education and Research in the DeWitt C. Baldwin Institute for Interprofessional Education and is also a Clinical Assistant Professor in the Interprofessional Health Studies program.

Dr. Thuente received her PhD degree in Nursing from Loyola University. She also holds a Bachelor of Science in Nursing and Master of Science in Nursing from Loyola and a Bachelor of Arts in Business from Wittenberg University. She completed the two-year Nurse Faculty Leadership Academy at Sigma Theta Tau, the nursing honor society.

Prior to joining the Baldwin Institute in 2016, Dr. Thuente was the Assistant Director of DePaul University’s School of Nursing: Master’s Entry into Nurse Practice Program located on the Rosalind Franklin University campus. Dr. Thuente’s previous role as a faculty member for both DePaul University School of Nursing and Loyola University Marcella Niehoff School of Nursing has provided extensive experience in teaching, curriculum development, assessment, and evaluation. Dr. Thuente’s clinical focus is in pediatrics, specifically oncology and cardiology.

Dr. Thuente’s educational and clinical background in nursing provides an excellent foundation for the research she conducts in interprofessional collaboration as a means to improve patient safety. Her doctoral dissertation determined a grounded theory of nurse-physician collaboration and verified the steps in the social process of collaboration. Her interprofessional research findings have most recently been published in the Journal of Nursing Education and the Journal of Allied Health. Dr. Thuente has recently presented at conferences including, CAB VI, NEXUS and ASAHP. MEDSURG Nursing awarded Dr. Thuente with their 2016 Research for Practice Writer’s Award for her article “Working Together Toward a Common Goal: A Theory of Nurse-Physician Collaboration.”

Catherine Gierman-Riblon

Catherine Gierman-Riblon DSc, MEd, RN is the Associate Dean for Online Programs, as well as an Associate Professor and Chair of the Interprofessional Healthcare Studies Department at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science. With thirty years of experience designing and delivering curricula for the health professions, and managing academic departments in institutions of higher education, she currently Chairs the Department of Interprofessional Healthcare Studies and coordinates the doctoral programs in Interprofessional Healthcare Studies and the Master of Science in Health Professions Education, both of which are offered as fully online degree programs.