TEAM-BASED LEARNING: An overview of Team-Based Learning design, guidelines and strategies

Contents

Introduction

Encouraging active learning has been said to be one of the effective strategies to increase students’ ability to comprehend, retain and apply information in the classroom. Working in small teams or groups is one way for instructors to engage students and facilitate active learning.

Several different approaches using groups as a central learning tool in the classroom are available, such as Cooperative Learning (Cooperative Learning), Process Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning (POGIL; Brown, 2010), as well as Team-Based Learning (TBL; Michaelsen, Knight, & Fink, 2002). One common design element for group work is to find ways to allot in-class time primarily for higher-level learning, such as applications and critique of the material as well as problem-solving. Some models incorporate occasional in-class group connections, but Team-Based Learning intentionally and strategically places students into stable small group for the duration of the course. This model promotes active learning, communication and team collaboration, while also emphasizing the importance of individual accountability. This module provides an overview of Team-Based Learning design, guidelines and strategies on ways to incorporate team-based learning into the classroom.

For a brief introduction to TBL, see this video below

Objectives

After completing this module you will be able to:

- Describe the three-step process of using TBL in the classroom and some best practice tips from the author.

- Discuss underlying principles of TBL.

- Envision how TBL could be used in your course using principles, strategies, and resources presented.

- Introduce and “sell” TBL to students.

UDL Alignment

Module Alignment

Each College STAR module seeks to explain how a particular instructional practice described within the module aligns with one or more of the principles of UDL. For this module, the focus will be on Providing Multiple Means of Representation and Multiple Means of Engagement.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Representation

In addition to ways of learning often found in traditional classrooms (e.g. lectures, video clips, and classroom discussions), one unique aspect of TBL is via the apprentice model, which allows students to share and explain information to one another beyond relying on instructor lecture or text or video. This peer-presented information becomes one more way students can hear/see concepts taught in the course.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Engagement

TBL’s three-step cycle (pre-class preparation, in-class readiness assurance testing (RAT), and application-focused exercises) provides ample opportunity for individuals and groups to provide both oral and written responses and presentations to questions, discussions and assignments. Students are interacting with the material individually, with one another in groups, and with the instructor in class. For instance, students are given opportunity to discuss how they might disagree with a peer’s response to a question during the readiness assessment test, thus giving them an opportunity to articulate their thoughts and clarify any questions they might have. Depending on the types of application-focused exercises given they might be given, TBL provides a learning environment for students to develop and refine effective communication and collaboration skills. Working within teams increases opportunities to have peer mentoring and feedback, which is guided and facilitated by the course instructor. When structured effectively, peer cooperation with flexible group roles can motivate and engage students through hands-on learning and opportunities to practice skills needed to work with others. Also, using tools such as IF-AT cards, voting cards, pushpins, or sticky notes can help engage the students beyond the traditional ways of group work.

Instructional Practice

Getting Started

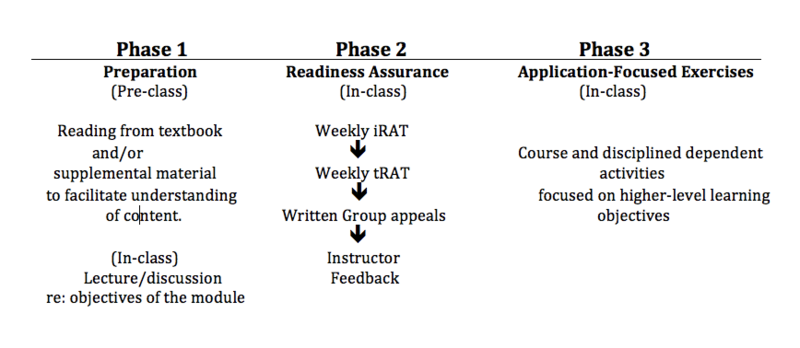

First developed by Larry Michaelson in 1979, TBL has been said to help students apply course content to authentic, real life problems (Sweet & Michaelsen, 2012). A typical TBL course is divided into five or seven modules, or units of learning, each containing a three-phase cycle (Sibley & Spiridonoff, n.d).:

- out of class pre-class preparation,

- in-class readiness assurance testing,

- application-focused exercises.

According to Sweet and Michaelsen (2012) For each TBL module:

- Pre-class preparation: Before coming to class, and in their own time, students are expected to complete assigned readings and additional learning materials. Related to a crucial element of TBL – student accountability – pre-class preparation is crucial as students will not be able to contribute meaningfully and work with one another if they do not come to class prepared. Format of pre-class preparation can include:

- Reading textbook or supplemental materials

- Review of web-based resources, lectures and other videos

Best Practice Tip:

Making sure pre-class preparation material assigned is realistic for students to complete and comprehend on their own will increase students’ self-efficacy and motivation to complete the task prior to coming to class.

- Readiness Assurance Process (RAP): RAP occurs when students come to class and typically consists of readiness assurance testing (RAT), written appeals, and instructor feedback:

- iRAT: Students first take individual readiness assurance testing (iRAT) where they are being tested on the main concepts of the module on their own.

- tRAT: The same test is then taken again within groups, which is called team readiness assurance testing (tRAT).

The two parts of RAT are designed to increase student accountability and readiness, as iRAT gives them incentive to do the assigned reading and perform well for themselves, while the tRAT provides more social incentive for students to be able to do well as a group and discuss or explain core concepts to their peers (Stein, Colyer, & Manning, 2016).

Formats of iRAT & tRAT that can be used include:

- Multiple-choice questions

- Fill-in-the-blank

- Essay questions

For tRAT, using Immediate Feedback Assessment Technique cards Ò (IF AT) cards within teams (or any sort of response card, clicker, or no tech, low tech, or high tech immediate feedback resource) can be a fun and effective way of engaging students while providing instant feedback about their answers.

An IF AT (“scratchoff”) card is a tool that can provide immediate feedback for individuals and teams, as it provides feedback on individual mastery of the assigned reading and whether or not they have discussed and considered input from team members in order to achieve their goal (e.g. answer correctly in teams as to get as many points as possible for tRAT). Even if teams do not answer correctly on their first try, members still get the immediate feedback as well as the experience of working together to find the right answers.

For more information on what IFAT cards are and how to use it, please see this video. But remember, there are plenty of no-cost to low-cost ways to create the same learning experience in class if your school does not have the funding to purchase proprietary materials.

Best Practice Tip:

One tip to keep in mind while designing RAT is to keep some aspects of it easy enough for students who did the reading can do fairly well on most of the questions, while ensuring there are some more complex questions that may be difficult for them to answer on their own, giving them incentive to work in teams when doing the tRAT.

Typically, after RAP is completed, the instructor may provide a mini lecture or brief explanations to clarify any points that remain unclear (Fink, 2003).

- Appeal: Once team members have taken the test as a group, they may appeal a question if they feel like they can provide a written response justifying the choice they have made using any resources available to them (e.g. textbook, notes and additional course resources). This can also occur if and when the questions were poorly written and ambiguous. In these situations, teams will explain their reasons for appeal and provide a more effective and improved wording for the question. Best Practice Tips:

- Appeals can only be written by teams, not individuals.

- Appeals must consist of arguments and evidence.

- Provide examples of an effective appeal to show students, such as

Argument: On question 8, A and B can both be considered correct.

Evidence: While lead can be considered a teratogen that may be harmful for fetal and postpartum development, there is inconclusive evidence of how much lead consumed or present in the human body will cause definite and permanent harm. Also, it is impossible to avoid lead at 100% as it can be found organically in food regardless of how much prevention is taken.

- Clarifications:

Application-focused exercise:

The final component of TBL is the practical application of course concepts through classroom team activities. The goal of these application exercises is to encourage students to work with each other and solve problems presented to them within their respective teams. Typically, as the students become more comfortable with the material and their teammates, the complexity and difficulties of the activities increases to provide appropriate challenge. After the exercises are complete, there is a “debrief” classroom discussion where students receive feedback on their presentations.

Designing TBL Classroom: Infusing Four Principles into Three-Step Process

One way to distinguish TBL from other “team-centered” pedagogies is its four underlying principles (Michaelsen & Sweet, 2008): 1) Permanent group membership, 2) Student accountability, 3) In-class assignments, and 4) Feedback.

Permanent group membership:

Students should be intentionally and properly placed in groups. Once formed, group memberships are fixed permanently for the duration of the course, where group dynamics are managed in order to ensure success and longevity of groups.

Having permanent group membership has been said to foster a sense of belongingness and can contribute to students’ knowledge of their own and others’ strengths, growth edges and how to allocate resources in any given class assignments.

To maximize the chance of groups being successful, the aim is to have as much diversity and randomization as possible when forming teams.

Tips to team-formation:

- Use teacher-formed groups and never student-formed groups.

- When forming groups, factors such as student GPA, major, years in school, learning styles, interests, strengths and any prior experiences with TBL should be considered and distributed equally among the groups, as much as possible to encourage diversity. This information can be elicited at the beginning of the course by surveying students.

- Be sure to avoid existing groups. This can help to minimize previous relationship dynamics between group members that might impact current groups and/or prevent the group from forming successfully.

- Be transparent with students about this process and emphasize your intentionality to ensure no special advantages are given to any group.

- A typical recommended group size is 5 to 7 students (Sweet & Michaelsen, 2012). This provides enough group members to contribute resources and abilities to any given task in class even if some members are absent.

For more about forming teams the TBL way watch this five – minute video:

Student Accountability

Students often complain about having to work in teams, expressing fears about having “free-riders” (who benefit without contributing much effort or team members), team members who might disruptive when they are present, or those who take charge too quickly without listening to the rest of the group. All these factors can contribute to an overall dislike for any instructional approach that ensures their learning and grades depend on that of others (Stein, Colyer, & Manning, 2016). This is where assuring accountability can contribute to a successful TBL classroom experience. All students are accountable for learning, meaning that they should come to class prepared and able to work and engage effectively in teams.

Student accountability is particularly important to take into consideration not only when designing the course, but at the beginning of the course when TBL is explained to the students in hopes of soliciting “buy-in”. This can be accomplished at the beginning of the course with students by explaining features built in to the TBL model that ensure individual responsibility prior to and during class and how this individual accountability will contribute to their success. Follow up by emphasizing the role of accountability emphasized throughout the course.

Tips for Promoting Accountability:

- Group grades give students incentive to collaborate and build teams, while peer assessments are also implemented, which are used to differentiate grades across team members, based on varied individual contributions (Fink, 2002).

- Students still receive grades for their individual performance and thus are motivated to complete pre-class preparation in order to perform well in-class individual test.

- Giving students rationale, tools and incentives to be accountable can go a long way and provide students with additional tools to use during the course. For instance, one way to do this is to tell students about feedback from previous TBL students and how they succeeded.

In-Class Assignments:

Team assignments must promote both learning and team development. When designing assignments, it is important that the assignments require students to apply course concepts and use higher order thinking skills accomplish the tasks.

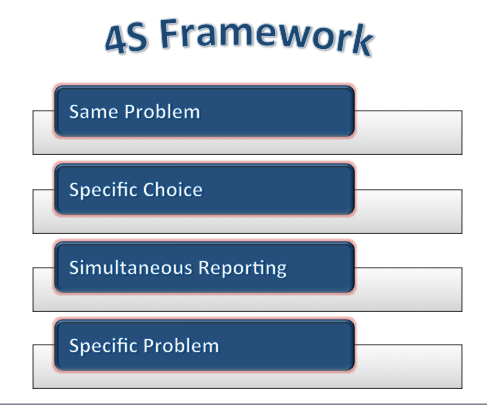

This is when the 4S framework comes in handy:

To maximize the effectiveness of the Application Activity, use the 4 S’s to get the most consistent and powerful results (Sweet & Michaelsen, 2012).

- Significant problem

- Same problem

- Specific choice

- Simultaneous report

- Significant problem: Because the goal is to have students work meaningfully and effectively in teams, the problem or task they have to solve should be designed with that goal in mind. This means the Significant Problem should be complex enough for the whole team to engage and not just done individually. This can be a task with partial, diverse and even contradictory information where in-depth discussion and decision-making may be involved in order to complete the task.

- Same problem: The second S refers to having different teams work on the same problem at the same time. The rationale behind this is to build engagement as well as basis of common knowledge and application of the same problem in small teams first and continue to do in a classroom-wide overall discussion or debriefing. Having similar starting points while engaging in individual team processes will also enable teams to provide more informed critique of other teams’ end product if there are conflicting and varying responses.

- Specific Choice: The instructor can pose a question for teams to discuss and require them to take a stance on an issue. The purpose of including specific choice is to set up the course in a way so that the team members have to all agree on a single, clearly-defined answer in spite of potentially vague or conflicting information. While teams can be encouraged to write down explanations or verbalize their rationale for their stance later, they must first be able to express their solution to a problem using “an easy-to-describe choice”, such as requiring students to answer a multiple-choice question that is complex and significant (e.g. using technology below a specific age is more beneficial or harmful to children’s development?). Presenting their response using specific choice also allows for the team to quickly see responses of other teams, which can then lend itself to further meaningful discussions or debates.

- Simultaneous reporting: The final “S” requires that all teams respond and report to the class at the same time. Requiring teams to answer in form of a specific choice (the third “S”) makes the final S possible. Since they are all working on the same problem, the rationale for simultaneous reporting is to promote fairness as there will not fighting over which teams go first or last, nor will later teams be able to change or modify their answers based on what previous teams said. Simultaneous reporting also encourages team accountability as they have to publicly report their results, which will also prompt more serious engagement in the activity leading up to reporting. When designed appropriately, simultaneous reporting can create excitement for the “great reveal” and promote engagement in the classroom, as teams would want to see how their response compares to those of their classmates.

Tools for simultaneous reporting includes using

- “A, B, C, D” voting cards to indicate right answers

- pushpins (or sticky notes) to visually indicate locations on a map

- whiteboards to write out responses

- poster gallery walks to visually showcase individual group’s work

- scissors and glue stick to allow the groups to copy and paste their responses.

- stacked overheads to compare between-group responses.

For more information on Simultaneous reporting, please see http://learntbl.ca/what-is-tbl/structured-problem-solving/

Frequent and immediate feedback must be given to students to promote learning. This applies to iRAT, tRAT and applied activities whenever possible (Sweet & Michealsen, 2012).

Best Practice Tips:

- For iRAT, instructor can grade iRAT when students are taking the tRAT. For quicker and easy grading, scantron testing sheets can be used (or electronic “voting” systems). Even if scantron are not available for grading, answers can be printed on clear overhead sheet to quickly identify correct and incorrect responses. Students are encouraged to write down their answers on a separate sheet of paper, so their answers can be retained for tRAT.

- For tRAT, as previously mentioned, IF AT cards are quick way for students to receive feedback.

- As for applied activities, it is helpful for instructor to walk around and give comments and feedback to teams as they are engaging in solving the problem. Feedback can also be given in whole-class discussion to debrief and conclude the applied activities.

Many students are often “too nice” to say something to their classmates, fearing that they might overstep, say something wrong, or simply do not know how to provide feedback. Others might be direct and assertive with comments that may end up feeling to peers like personal attacks. Neither of those groups are delivering effective feedback. Thus, one way to overcome this is to go over Haslett and Ogilvie’s (2003) eight specific communicative strategies for giving and receiving effective feedback at the beginning of the course.

These guidelines can be useful to facilitate intra-team, inter-team and whole-class discussions:

- Be specific and direct

- Support comments with evidence

- Separate issue from person

- Sandwich negative comments between positive ones

- Pose the situation as a mutual problem

- Soften and mitigate negative messages to avoid overload

- Deliver feedback close to occurrence

- Use effective delivery that includes being assertive, dynamic, trustworthy, fair, credible, relaxed and responsive, and must preserve public image of the recipient.

Sweet and Michaelsen (2012) proposed a slightly different framework to conceptualize TBL by focusing on four practical pieces: 1) Proper Teams, 2) Readiness, 3) Application and 4) Peer Evaluation. As the first three components have been mentioned previously, the role of peer evaluation in TBL classrooms is highlighted below.

Peer Evaluation

Peer evaluation has been said to be the most context-sensitive aspect of TBL, as this may vary depending on the instructor’s teaching style, classroom culture or external context such as field of discipline. It is an important aspect of TBL because it minimizes, or at least gives a chance to expose “free-riders” who may not come to class prepared or contribute much to team activities in class.

Sweet and Michaelsen (2012) made the following recommendation when thinking about how to construct student-to-student peer evaluations:

- Describe HOW and WHY of peer evaluation on the first day of the course. As one common student resistance to team work is “free-rider”, or absent, inactive, distracting, noncontributing team members, describing HOW the peer evaluation works and WHY it is important to have peer evaluation in a TBL classroom on the first day can help set the tone and decrease student resistance. Acknowledge undesirable aspects of peer evaluation while also talking about how it can be used to enhance group and personal development. As an example, in my classroom, I typically say something along the lines of:

“It may feel like extra work, and it’s true that it does take time, but getting honest and constructive feedback from your peers can be beneficial to see what is working well and how you can take it to the next level. Giving effective feedback takes practice and we will get a chance to practice that in this class, so when it’s time to do it when you start your career, you’d already be a pro!”

- Brainstorm with students about criteria that should be included in the evaluations. By including students in the evaluation process as much as possible, you can help students feel empowered by hearing and acknowledging their voices in the design of course evaluation. This may help with buy-in and acceptance of evaluation process, which is likely to lead to more meaningful feedback. Here is something that I’ve said in the past to students:

“Here are several criteria for team members to evaluate each other that I have typically used in the past when I’ve implemented TBL in the classroom. What else might be important to add to the list?”

- Use both numeric ratings and qualitative narratives in evaluations. For me, I like to use the “sandwich” approach of starting feedback with something positive and concrete, then give constructive feedback before wrapping up my comments with something encouraging and “action-oriented” whenever possible.

“John, I’d give you a 4.5/5 for your contribution to class presentations. I can tell that you always come prepared to class, is reflective and contributes your thoughts whenever you can. I appreciate what you have to say. One thing I’d encourage you to do is to speak up more!”

“I’d give you a 4/5 for your contribution to class presentations. Maria, you have such unique perspectives being an education major, our group is stronger because of you. It is distracting when you are texting constantly, though.”

- Periodic evaluations instead of just “end of semester evaluation”. Evaluation should be gathered periodically (e.g. midterm and final) for team members to continue implementing what works and change or improve their growth edges. This way, peer evaluation can be used partway through the course, instead of just at the end, which may feel more punitive. The narrative below is something that I either say to students directly in class, or have even used in announcements for online courses to be transparent and explain my rationale for evaluations.

“Have you ever filled out a course evaluation for instructors at the end of the course for a semester and dislike the idea if the professor takes into account your feedback, you would not benefit from the changes that YOU suggested? In this class, we are going to try to avoid that as much as possible by doing a midterm evaluation, as a mid-point check in to see what is going well and what can ‘go better’ for the second part of the course?”

- Evaluation should include feedback for team members and instructor. Not only can instructors change any problems or concerns that students might have based on the “middle of the course” evaluation, it also gives instructors the opportunity to role model how to receive and utilize feedback – something that can enhance a “we-are-all-in-this-together” mentality and equalize the power differential between instructor and students. I have found that students are generally receptive to this idea when they understand why feedback is important and how it might be used, so I typically give a context like the one below:

“As I am also part of our class’s learning community, in addition to evaluating your team members, you will also get a chance to give me feedback. While I have taught this course various times in the past, each class is a little different and your needs might be a little different individually and as a group, so I would very much appreciate the opportunity to find out what aspects of my teaching and facilitation that have worked and other aspects that could be changed improved. While it may not be realistic to always implement everything that you suggest, but know that I do read them and strive to use feedback to maximize your learning.”

- Consider the levels of anonymity in the evaluations. There are varying perspectives on how much team members should be able to see of one another’s grades when it comes to evaluations. For instance, while some might advocate for total transparency of scores and the identity of those who wrote specific feedback comments, others have suggested that moderate anonymity, (where numeric ratings and qualitative comments are shared with students without knowing who wrote the individual responses) is best.

- Differentiation of scores in the evaluations. Consider encouraging students to be honest, and differentiate peer evaluation scores based on actual contribution of each member. Often times, students will want to be “nice” and give everyone high scores to avoid discomfort or potential conflict. Once again, depending on the context of the course and institution, gentle yet explicit reminders of “giving the same scores hurts those who actually contribute” might go a long way to help students differentiate their scores for each other.

Ways to sell TBL to students

Students who haven’t experienced TBL classrooms before may have preconceived notion of how difficult and exhausting group work can be and, as a result, be fundamentally opposed to the idea of “team work”. They also may be anxious about having their grades depend on the performance of others. Instructors who have implemented TBL have reported student resistance at the beginning of the course, and some of this may stem from lack of communication of benefits and rationale for using TBL. Thus, one way to successfully kick off the implementation of TBL is to address this from the get-go and explain what TBL is and address any hesitation students might have. Describe how the model can benefit student and descriptions about how you, as the course instructor, can help.

Instructor’s Active Role in Student Learning

As opposed to traditional classroom lectures, one of the advantages of TBL for instructors is their ability to play an active role in facilitating student learning. Learning within a TBL classroom is not solely reliant on lectures, so the instructor can serve as guide or facilitator of learning by providing frequent and immediate feedback in the moment whenever needed and appropriate. To translate that concept for students:

“Have you ever been bored during a lecture and wish you didn’t have to listen to things that you could read on your own from the textbook? TBL is not about learning through lecturing. You are in charge of learning on your own before class and then within teams when you come to the classroom. My role is to facilitate and maximize learning by giving more personalized feedback based on my observation, our discussions and your team’s reporting.”

Peer Discussion and Feedback

When implemented correctly, one advantage of learning in a TBL classroom is that students get the “best of both worlds.” In other words, they are accountable for their own learning as well as given an environment to collaborate with, evaluate, and give feedback to group members. As researchers (Smith, Wood, Krauter, & Knight, 2011) have suggested, peer discussion combined with instructor explanation appear to be more effective in enhancing most students’ learning than either approaches alone. TBL does just.

“You are in charge of your learning, but I can help”

One potential disadvantage of TBL is when students do not come to the classroom prepared, they are limited and unable to contribute meaningfully to team work.

With the amount of work and testing involved in TBL, it is relatively easy to identify students who may be struggling early in the course, which can be used as information for instructors to reach out and offer more individualized feedback and observation to help students catch up. For example, I have said something to students in the past along the lines of:

“Hi John, I wanted to touch base with you, as you seemed to have been struggling with the iRATs and do not speak up much in the team. Learning in a TBL classroom can be difficult at first, especially if you are not used to teams and there are a lot of pieces that rely on you, but I do not want to see you struggle on your own. Let’s set up a time to talk about what might have been preventing you to be successful in the course so far, as it is still early in the semester and I would like to help.

Learn More

Literature review

While there are numerous group-oriented learning models, TBL is the only form of small-group learning that emphasizes the transition from “groups” to “teams”, as students build trust over the course of the semester (Fink, 2003). First developed by Dr. Larry Michaelsen in the 1970s, TBL was implemented in a business school course within a classroom of 120 students with aims of helping students engage in in-depth discussion and apply concepts to real-world problems (Michealsen, Parmelee, McMahon, Levine, & Billings, 2008). From then and until now, TBL has since been adopted and validated by many disciplines around the world (Haidet et al, 2012).

The American Association of College and Universities list teamwork and problem solving, critical and creative thinking, written and oral communication, information literacy, as well as inquiry and analysis among essential skills for graduates of higher education (AACU, 2007). A well-designed TBL course lends itself with ample opportunities for students to develop and refine these skills. Results from studies have offered additional evidence of students having increased knowledge retention as well as problem solving skills (e.g. McInerney & Fink, 2003; Touchet & Coon, 2005) as a result of TBL, further supporting the rationale for using TBL to help students integrate content into practice and prepare them for the “real-world”.

Additional benefits of instructor-led, learner-centered TBL classrooms are numerous. Studies have shown higher level of student engagement (Chung, Rhee, & Baik, 2009), as well as increased excitement for both students (Palsolé & Awalt, 2008) and instructors (Haidet & Fecile, 2006; Lane, 2008) in TBL courses. Implementing team-based learning also appeared to contribute to positive learning outcomes, such as higher scores in final exams and standardized tests (Cheng, Liou, Tsai, & Chang, 2014). In several recent studies (Dana, 2007; Fatmi, Hartling, Hillier, Campbell, & Oswald, 2003), including a recent meta-analysis of data from 225 studies (Freeman, Eddy, McDonough, Smith, Okoroafar, Jordt, & Wenderoth, 2014), students enrolled in active learning performed better on exams compared to their counterparts enrolled in classes that use traditional lectures; active learning is a key ingredient in TBL courses.

In spite of the various documented advantages of adopting TBL, student resistance does present challenges for faculty. It can also be time-consuming and emotionally challenging for faculty to redesign a course to be consistent with TBL principles. Faculty members new to this process may want to create learning communities or seek other faculty’s support and expertise when undertaking the redesign (Andersen, Strumpel, Fensom, & Andrews, 2011).

References & Resources

American Association of Colleges and Universities. (2007). College learning for the new global century. Washington, DC: AACU.

Cooperative Learning Institute. Retrieved from http://www.co-operation.org/.

Andersen, E. A., Strumpel, C., Fensom, I., & Andrews, W. (2011). Implementing team based learning in large classes: Nurse educators’ experiences. International journal of nursing education scholarship,8(1), 1-16.

Brown, P. J. (2010). Process-oriented guided-inquiry learning in an introductory anatomy and physiology course with a diverse student population. Advances in physiology education, 34(3), 150-155.

Cheng, C. Y., Liou, S. R., Tsai, H. M., & Chang, C. H. (2014). The effects of team-based learning on learning behaviors in the maternal-child nursing course. Nurse Education Today, 34(1), 25-30.

Chung, E. K., Rhee, J. A., & Baik, Y. H. (2009). The effect of team-based learning in medical ethics education. Medical Teacher, 31(11), 1013-1017.

Cooperative Learning Institute. (n.d.) Retrieved from http://www.co-operation.org/.

Dana, S. W. (2007). Implementing team-based learning in an introduction to law course. Journal of Legal Studies Education, 24(1), 59.

Fatmi, M., Hartling, L., Hillier, T., Campbell, S., & Oswald, A. E. (2013). The effectiveness of team-based learning on learning outcomes in health professions education: BEME Guide No. 30. Medical Teacher, 35(12), e1608-e1624.

Fink, L. D. (2002). Beyond small groups.Team-based learning: A transformative use of small groups. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Fink, L. Dee. 2003. Creating Significant Learning Experiences: An Integrated Approach to Designing College Courses. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410-8415.

Haidet, P., & Fecile, M. L. (2006). Team-based learning: A promising strategy to foster active learning in cancer education. Journal of Cancer Education: The Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Education, 21, 125-128.

Haidet, P., Levine, R. E., Parmelee, D. X., Crow, S., Kennedy, F., Kelly, P. A., & Richards, B. F. (2012). Perspective: guidelines for reporting team-based learning activities in the medical and health sciences education literature. Academic Medicine, 87(3), 292-299.

Haslett, B. B., & Ogilvie, J. R. (2003). Feedback Processes in Task Groups. In Hirokawa, R. Y. Cathcart, R. S., Samovar, L. A., & Henman, L. D (Eds), Small Group Communication Theory & Practice: An Anthropology (p 95). New York: Oxford University Press.

Lane, D. R. (2008). Teaching skills for facilitating team-based learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 116, 55-68. doi: 10.1002/tl.333

McInerney, M. J., & Fink, L. D. (2003). Team-based learning enhances long-term retention and critical thinking in an undergraduate microbial physiology course. Microbiology Education, 4, 3.

Michaelsen, L. K., Knight, A. B., & Fink, L. D. (Eds.). (2002). Team-based learning: A transformative use of small groups. Greenwood publishing group.

Michaelsen, L. K., Parmelee, D. X., McMahon, K. K., Levine, R. E., & Billings, D. M. (2008). Team-based learning for health professions education: A guide to using small groups for improving learning.

Michaelsen, L. K., & Sweet, M. (2008). The essential elements of team-based learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2008(116), 7-27.

Palsolé, S., & Awalt, C. (2008). Team based learning in asynchronous online settings. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2008(116), 87-95.

Sibley, J., & Spiridonoff, S. (n.d.). Introduction to Team-based Learning. Retrieved August 3, 2017, from https://c.ymcdn.com/sites/teambasedlearning.site-ym.com/resource/resmgr/Docs/TBL-handout_February_2014_le.pdf

Stein, R. E., Colyer, C. J., & Manning, J. (2016). Student accountability in team-based learning classes. Teaching Sociology, 44(1), 28-38.

Smith, M. K., Wood, W. B., Krauter, K., & Knight, J. K. (2011). Combining peer discussion with instructor explanation increases student learning from in-class concept questions. CBE-Life Sciences Education, 10(1), 55-63.

Sweet, M., & Michaelsen, L. K. (2012). Team-based learning in the social sciences and humanities: Group work that works to generate critical thinking and engagement. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Touchet, B. K., & Coon, K. A. (2005). A pilot use of team-based learning in psychiatry resident psychodynamic psychotherapy education. Academic Psychiatry, 29(3), 293.

Chu-Chun Fu

Chu-Chun Fu is an assistant professor in Department of Psychology at Fayetteville State University in Fayetteville, NC. With the mindset of maximizing class time and preparing students for future career success, she began incorporating team-based learning in addition to other teaching strategies in her undergraduate Developmental Psychology since 2017.