Universal Design for Learning in a Digital Environment Using the STAR Legacy Pedagogy with Transitional Doctor of Physical Therapy Students

Contents

Introduction

The purpose of this case study is to describe how using STAR Legacy Pedagogy can assist learners in solving authentic problems. First described will be how the STAR Legacy Pedagogy promotes learning for diverse students who have varying levels of professional expertise in a post-professional Doctor of Physical Therapy program. Secondly, the UDL alignment will be discussed. Finally, the methodology for integrating this pedagogy will be depicted, and student learning outcomes will be presented.

Teaching students in any academic discipline how to solve authentic problems can be challenging. These problems often have multiple solutions, are seated in the context of experience, and require appropriate scaffolding that facilitates problem articulation, support for disciplinary knowledge, and a defined process (Quintaña et. al., 2004; Brush and Saye, 2002). In order to adequately convey content and facilitate problem solving, case based pedagogy that is supported with instructional scaffolding has been suggested as an effective evidence based strategy (Hayward & Cairns, 1998; Smith, 2018). One way to present cases using universal design for learning into technology-based environments is the STAR legacy pedagogy, which is designed for integration of case based pedagogy that provides scaffolding of the learning process. This scaffolding of the learning process is provided in three ways that are congruent to Quintaña’s (2004) recommendations for scientific problem solving that state that support should be provided for process management, disciplinary knowledge support, and articulation and reflection. First, from a process management standpoint, the STAR legacy pedagogy provides an implicit structure for problem solving in that it follows a cyclical process of learning where a problem is presented, resources to solve that problem are provided, and the learner is encouraged to provide solutions to the problem. Secondly, the STAR legacy pedagogy provides content knowledge support that is particular to the disciplinary problem. Finally, articulation and reflection, or support for metacognition, is provided as learners are asked to reflect on what they know, what they learned, and make an estimate of how much their knowledge has grown from the initial part of the learning module to the end of the learning module.

Objectives

After completing this case study participants will be able to:

- Identify how the STAR legacy pedagogy can be used to provide authentic learning for diverse learners in a post-professional graduate program.

- Identify how the STAR legacy pedagogy can be used to facilitate complex problem solving in health professions education and other fields.

- Make a plan for implementing STAR legacy pedagogy into digitally based environments.

UDL Alignment

Thinking about how the STAR legacy pedagogy aligns with the Universal Design for Learning Framework, one should consider that the STAR legacy pedagogy uses the How People Learn Framework. The How People Learn Framework “creates a learning environment where all of the important factors that influence how people learn are present and in balance for learning,” and is therefore learner centered, knowledge centered, assessment centered, and community centered (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000). Definitions for each of these facets of the How People Learn Framework are located in Table 1.

| Table 1. How People Learn Framework Factor Definitions (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000) | |

|---|---|

| Factor | Definition |

| Learner Centeredness | Understanding what knowledge, skills, and abilities the learner has upon classroom entry and how to scaffold learning for all students, regardless of ability level. |

| Knowledge Centeredness | Understanding what is taught (information), why it is taught and what competence a learner should have upon mastery of that knowledge. Includes making apparent why the information is important for the learner to know. |

| Assessment Centeredness | Providing formative assessments that make thinking visible during the learning process. Guides the instructor to make adjustments in the information presented to fit the level of the learner. |

| Community Centered | Designing classroom activities that connect to other class members or the community at large in which the person practices, bringing relevance to the learning exercise. |

The STAR legacy pedagogy engages these four facets of the How People Learn Framework by engaging, and attempting to balance the features of the learners, the knowledge presented, assessment, and community. This balance is optimized by delivering the lesson in a modular learning cycle (Figure 2) (iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu, n.d.).

Figure 1: The STAR Legacy Pedagogy Cycle of Learning

When thinking about how UDL principles are exhibited with the STAR legacy model, three framework principles are exhibited, namely engagement, action and expression, and representation. However, the primary principle exhibited by the STAR legacy model is engagement. This will be presented subsequently.

The UDL principle of multiple methods of engagement is exhibited in two ways in the STAR legacy pedagogy, by using case based learning and by informing learners of the module objectives prior to beginning the learning module. First, case based learning is intrinsic to the STAR legacy pedagogy in that the learning cycle begins with a “challenge”, which is in the form of an authentic case. This case can be anything that is pertinent to the learner, meaning that, the case should engage the learner in something that invites student inquiry and is relevant to their discipline. This engagement of learners in case-based learning inquiry has been shown to be effective in multiple disciplines as a strategy for encouraging better problem articulation and better knowledge integration (Smith, 2018). Secondly, the UDL principle of providing learner engagement was also encouraged by adding pre-work prior to the module that informed learners of the module objectives and module navigation, for the purposes of setting learner expectations for the module. This allowed engagement to occur due to the fact that learners interest was recruited, by providing learning outcomes that reflected a clear purpose to the participant, and by guiding appropriate goal setting by placing objectives in an obvious place.

Instructional Practice

I utilized this instructional module in an online Teaching and Learning Class for student enrolled in a transitional Doctor of Physical Therapy Program. In this learner context, the construct of universal design with case based pedagogy was important, as learners in the course have different levels of degree attainment (Bachelor’s or Master’s), differing levels of clinical experience, and different levels of knowledge of teaching and learning principles for the classroom or clinic.

The purpose for the module was to teach learners about how to instruct patients in the clinic in effective movement patterns by using a motor learning approach. This topic is relevant to physical therapists, as physical therapists need to use principles of motor learning to best encourage development of new motor skills in an efficient and safe manner. However, it had been difficult for me to communicate this topic in a virtual setting, as motor learning is a complex topic that involves multiple constructs including: types and schedules of feedback, practice schedules, task analysis, environmental construct, and changes that need to be made in instruction as the patient progresses. Therefore, I presented learners with a case based learning module that employed the principles of UDL through use of the STAR legacy pedagogy in order to provide an equitable learning environment that addressed: the complexity of the topic, students’ differing levels of initial learning attainment, and authentic assessment practices.

Module Construction

To begin the learning module, learners were given pre-work. This was not originally part of the STAR legacy framework, however, I felt that it was important to contextualize how the module fit into the course and how learners should navigate the online-only module (UDL guideline of Engagement). Therefore, the pre work consisted of learning objectives that directly related to the learning objectives found in the syllabus and the learning objectives from the readings in the book. In addition, learners were given a summary of how the module would proceed to help them navigate through the module. A summary of these instructions and objectives is below.

This module is designed to allow learners to discover important concepts of motor learning and be able to apply them to practice.

Objectives (Plack and Driscoll, 2017, p. 239):

- Describe the influence of motor control theories on the application of teaching and learning motor skills

- Identify the stages of motor learning and the focus of each stage of learning in skill development

- Classify motor skills according to existing taxonomies.

- Describe the conditions and variables that influence how motor skills are processed

- Relate the conditions of pre-practice and practice to outcomes in motor performance and motor learning

- Consider the role of providing feedback in effectively teaching motor skill acquisition.

- Apply the principles of motor learning to clinical case scenarios too enhance teaching and learning effectiveness and patient/client performance

Course objectives related to this module:

- Describe the strategies utilized to teach movement and the impact of feedback.

- Apply the principles of motor learning to an analysis of clinical teaching performed by a colleague.

This module is designed with the STAR Legacy model, which starts with a challenge (an authentic patient case), an assessment of previous knowledge, resources to help you learn, an assessment of knowledge gained (a non-graded quiz), and an opportunity to reflect on what you have learned. Required elements for completion of this module are: the Thoughts form, The Assessment (in the form of a quiz), the wrap up reflection, and the course evaluation.”

Following the STAR legacy model, the case started with a challenge (UDL Engagement and Action and Expression). The challenge was in the form of an authentic case. The case was as follows:

A physical therapist is working in an outpatient clinic with a competitive cheerleader (see Link (Links to a YouTube video.) if you don’t understand what this means) who has had an inversion ankle sprain due to landing on her ankle incorrectly after performing a tumbling pass. In conjunction with her coach, you are working to rehabilitate her ankle and also alter her movement patterns to prevent future injury.

The athlete is having a lot of frustration with altering her movement patterns to prevent injury and with learning new ways of landing to prevent injury. In addition, she states that sometimes she still ‘lands wrong’ in practice. Knowing that you are a movement system expert, the coach asks you to work with the athlete to determine what training and motor learning the athlete needs to do in order to maximize her ability to participate in her sport and prevent injury.

Using the information in the case, your job is to determine:

8. What type of feedback would the athlete utilize intrinsically?

- What training and feedback schedule the cheerleader should follow for 3 weeks in order to change her movement patterns?

- What type of motor skills should be encouraged in each part of the learning process (discrete, serial, or continuous).

- Should you use a guided approach vs. trial and error?

- What are the tasks involved in competitive cheerleading that could put the person at risk for injury? What tasks does the person need to be prepared to do?

- What type of practice should be used first? (whole or part), and why?

- What type and schedule of augmented feedback should be given when learning the skill initially? What about when the skill is progressing toward mastery?

- What type of practice environment would you have this athlete practice in initially? (open vs. closed) Why?

- What type of extrinsic feedback would you provide, and what type of fading schedule would you suggest?

- What type of practice schedule (massed vs. distributed, constant vs. variable, block vs. random, combination) would you suggest and why?

- How would your suggestions change as the athlete progresses towards return to sport. Why? (Consider the stages of learning).”

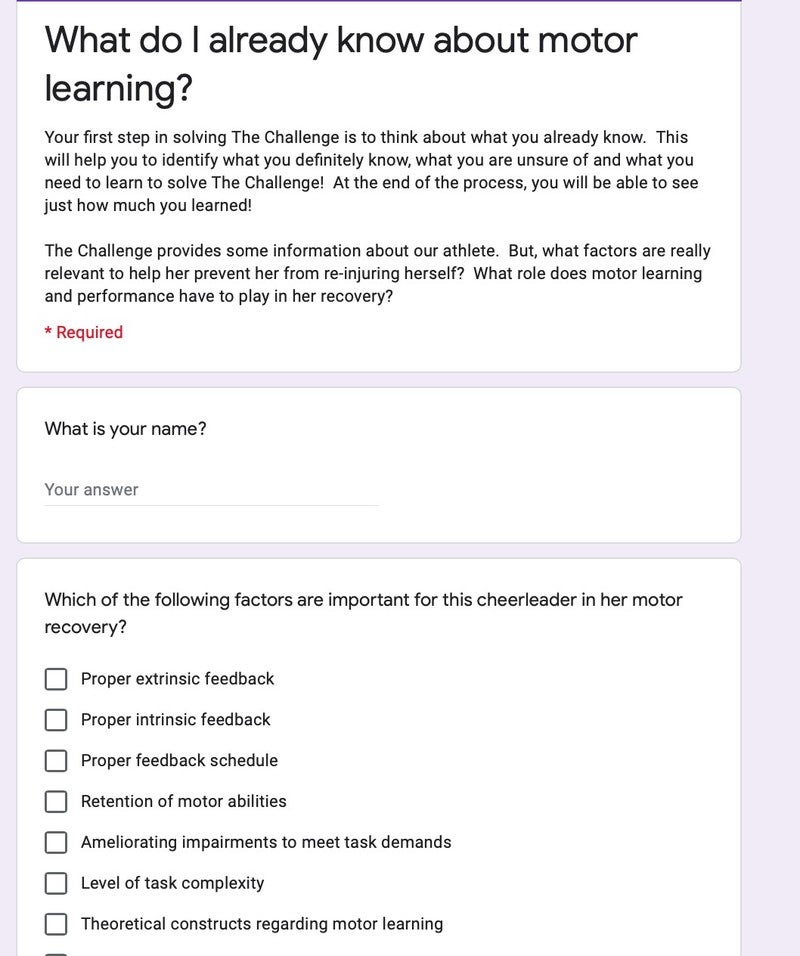

Next, learners were asked to convey their thoughts about the challenge (UDL Action and Expression) using a google form (Figure 2). This asked learners to answer questions about the case, and provided a way for the instructor to know what background knowledge learners had about the material, prior to proceeding to resources that provided them with more information. In addition, learners were asked to rate their overall knowledge of motor learning on a Likert scale (1=novice, 5=expert).

Figure 2: Thoughts about the Challenge

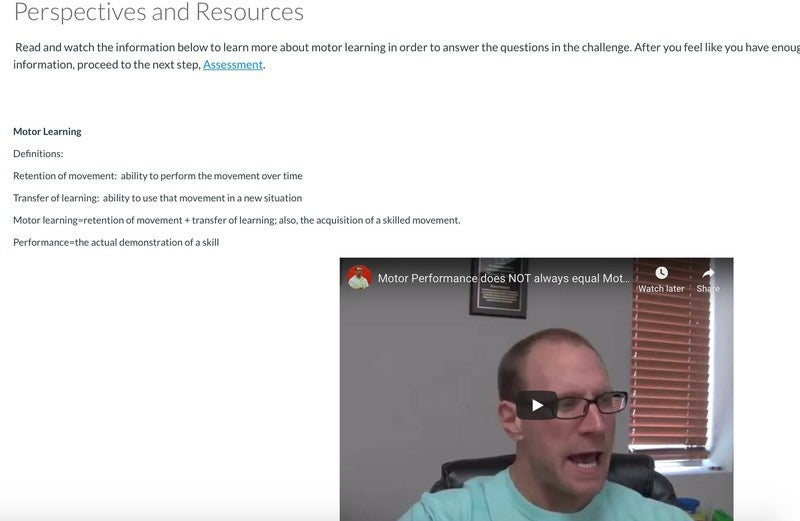

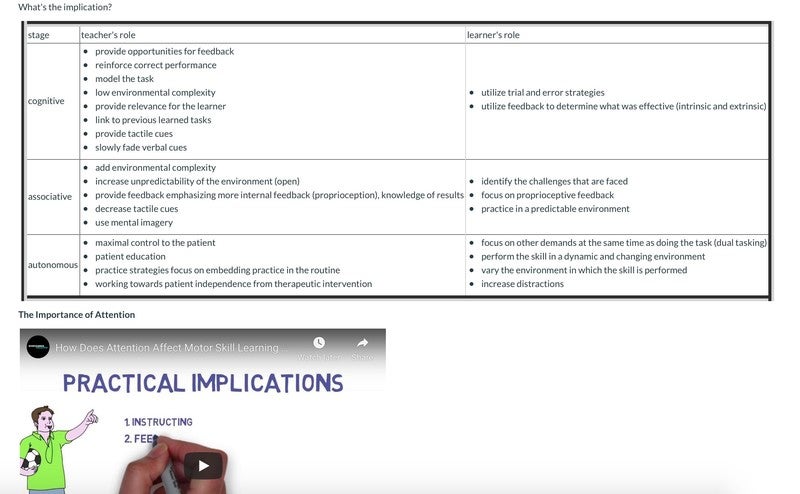

The next step in the STAR legacy pedagogy is to provide learners with Perspectives and Resources. This section gave multimedia information (UDL Representation) to learners that included summaries of what they needed to learn (text), videos from YouTube that provided information about motor learning (since captioning was available), and tables of information. The videos and textual information provided information needed to answer questions that were posed in the challenge, and were accessible to students from diverse geographic locations. The page was checked for accessibility through an accessibility checker and found to be compliant. An example of these resources is located in Figure 3.

Figure 3.1: Perspectives and Resources

Figure 3.2: Perspectives and Resources

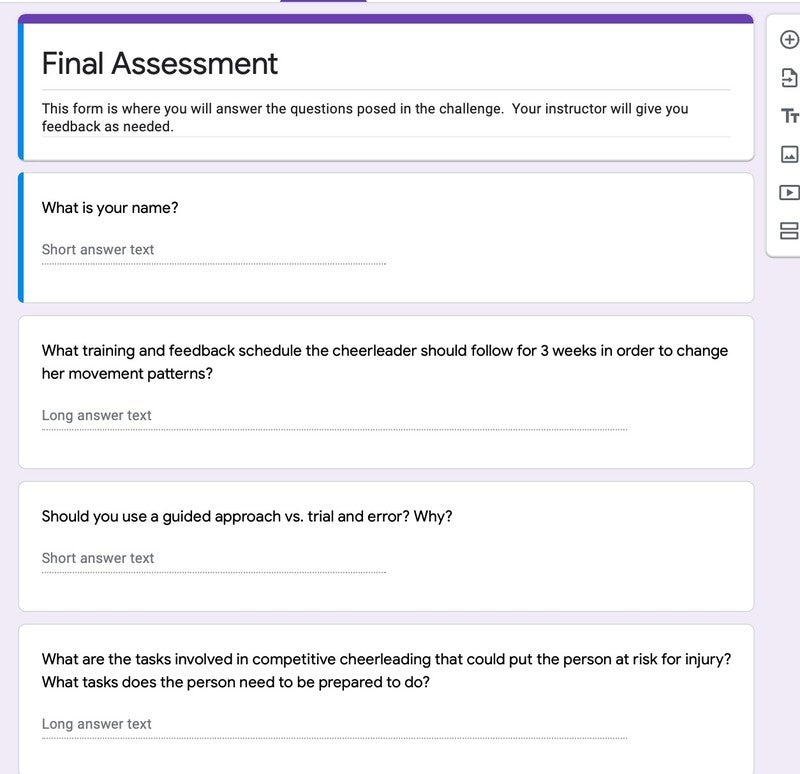

Next, learners participated in the assessment of learning (UDL Action and Expression). This assessment asked learners the same questions that were asked in the beginning of the module during the challenge and the thoughts section of the module using a google form. This form is depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Assessment of Learning

The last step in the STAR legacy pedagogy is wrap up (UDL Action and Expression). During wrap up, learners had an opportunity to reflect on their learning by answering three questions that were provided through a google form. These questions were:

- What are two things you have learned with this module?

- What did the module cover that you already knew?

- Rate your current knowledge of motor learning (1=novice, 5=expert).

Learner Feedback and Impact of the Module on Learning

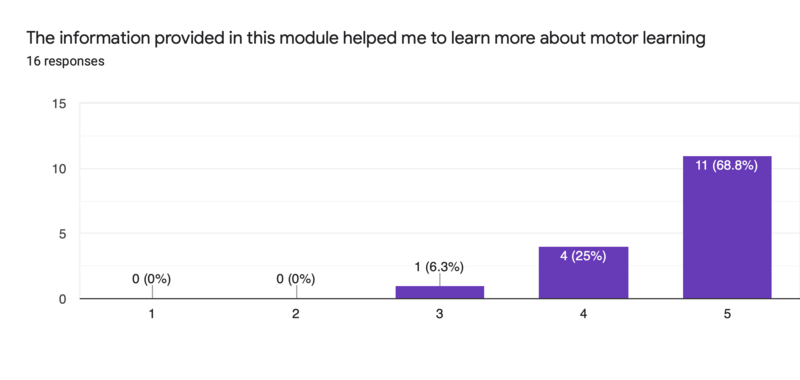

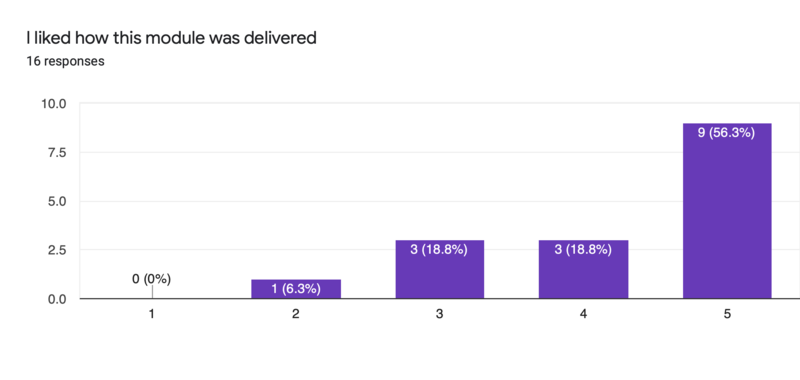

After completing the learning module, students had an opportunity to participate in an evaluation of the module though use of Likert and open ended questions presented via a Google form (https://forms.gle/6fPW7uCZZT6ckH649). Results of this evaluation revealed that 94% of learners either strongly agreed or agreed that the information provided in the module helped them learn more about motor learning (Figure 5), and 75% either strongly agreed or agreed that they liked how the module was delivered (Figure 6). Learners suggested that they “would not change anything about the module” or “would lessen the number of videos in the perspectives and resources section of the module”. This feedback has been implemented for future delivery of the module in the class.

Figure 5: Feedback from Students on how Information Helped Learning

Figure 5: Feedback from Students on how Information Helped Learning

Figure 6. Feedback from Students on liking how the module was delivered.

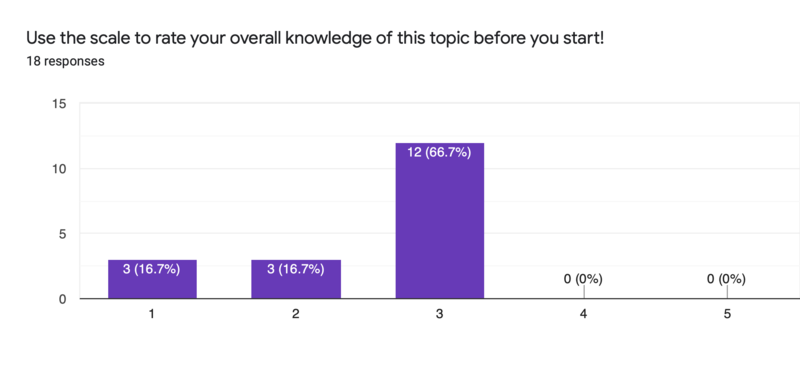

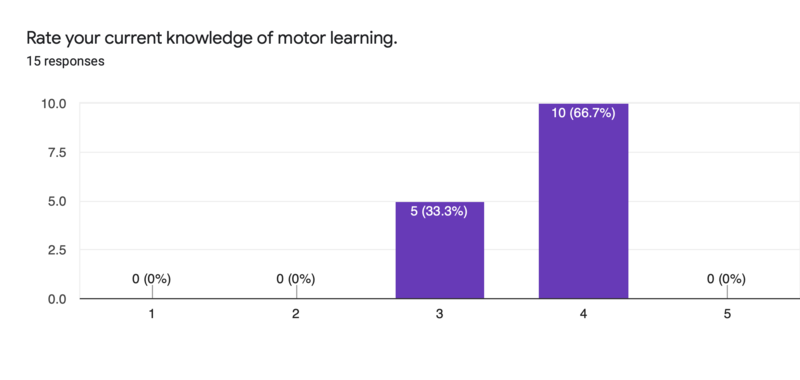

Another consideration that I had when evaluating learning was learner’s self-efficacy regarding their knowledge of the topic. Learners were asked to rate their knowledge of motor learning prior to and after participating in the module on a Likert scale (1=novice, 5=expert). Learners demonstrated a perceived increase in knowledge from pre-to post (mean pre 2.5, post 3.67). Considering this disparity, learning is considered to have occurred (iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu, n.d).

Figure 7. Pre-Knowledge Assessment

Figure 8. Post-Knowledge Assessment

Conclusion

By using the STAR legacy pedagogy, instructors can facilitate UDL principles, facilitate complex problem solving, and have demonstrable effects on learning and learner satisfaction. This balanced approach should be considered as instructors try to impact learners who need to develop into expert problem solvers.

Learn More

How People Learn: http://www.csun.edu/~SB4310/How%20People%20Learn.pdf

The STAR Legacy Pedagogy (a learning module): https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/hpl/#content

Adult Learning Theory and the STAR Legacy Pedagogy: https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/_archive/iris-and-adult-learning-theory/

Universal Design for Learning Framework: http://udlguidelines.cast.org/?utm_medium=web&utm_campaign=none&utm_source=cast-about-udl

References & Resources

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (2000). How people learn: brain, science, experience, and school (Vol. 11). Washington, DC: National academy press.

Brush, T. A., & Saye, J. W. (2002). A summary of research exploring hard and soft scaffolding for teachers and students using a multimedia supported learning environment. The Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 1(2), 1-12.

CAST (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Hayward, L. M., & Cairns, M. A. (1998). Physical therapist students’ perceptions of and strategic approaches to case-based instruction: suggestions for curriculum design. Journal of Physical Therapy Education, 12(2), 33-42.

IRIS & Adult Learning Theory. (n.d.). Retrieved December 12, 2019, from https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/_archive/iris-and-adult-learning-theory/.

Plack, M. M., & Driscoll, M. (2017). Teaching and learning in physical therapy: From classroom to clinic. Slack Incorporated.

Quintana, C., Reiser, B. J., Davis, E. A., Krajcik, J., Fretz, E., Duncan, R. G., . . . Soloway, E. (2004). A scaffolding design framework for software to support science inquiry. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(3), 337-386.

Smith, N. A. (2018). Facilitation of physical therapist student hypothetical deductive clinical reasoning using a scaffolded mobile application (Doctoral dissertation, North Carolina State University).

Technical Resources Utilized in Module Creation:

Learning Management System (Canvas)

YouTube (www.youtube.com)

Google Forms (Google Forms)

About the Author

Nancy Smith

Nancy Smith, PT, DPT, PhD received her MPT and DPT from Saint Louis University, and her PhD in Curriculum and Instruction at North Carolina State University. She is a certified clinical specialist in geriatrics from the American Board of Physical Therapy Specialists. Prior to teaching at Winston-Salem State University, she practiced in geriatrics and acute care for 11 years. In her practice, her experiences have ranged from practicing as a staff level therapist to managing multiple skilled nursing facilities clinically and operationally. Currently, Dr. Smith is an Associate Professor at Winston-Salem State University, where she teaches content in teaching and learning, cardiopulmonary physical therapy, and geriatrics. Dr. Smith has also presented locally and nationally on human patient simulation, and is currently doing research on the effects of technology and on student learning outcomes.