Using Quizzes to Increase Compliance

Contents

Introduction

Many professors affirm that compliance with reading assignments is vital to student learning (Hoeft, 2012). Getting students to comply with assigned readings is no easy feat, since the norm is for students to skip reading altogether. Professors are left, then, to determine how best to compel students to prioritize readings as assigned.

Dr. Melinda Kane, Assistant Professor of Sociology at East Carolina University, implemented weekly quizzes on assigned reading as a part of her pedagogy in 2000. Dr. Kane has perfected the instructional practice over the years. Initially, Dr. Kane chose to give quizzes only in lower level courses, but later expanded use of quizzes to upper division courses as well.

Dr. Kane includes an explicit explanation of the quiz requirement in the course syllabus and discusses the practice thoroughly with students at the onset of the course. Ultimately, using quizzes as a part of instructional practice encourages students to make Dr. Kane’s reading assignments a priority in order to come to class prepared. Students, then, are able to contribute to meaningful class discussion and they affect a key part of their course grade.

UDL Alignment

Each College STAR module will explain how a particular instructional practice described within the module aligns with one or more of the principles of UDL. For this module, the focus is on Provide Multiple Means of Representation, Principle I; and Provide Multiple Means of Engagement, Principle III. Quizzing students on pre-reading assignments not only offers multiple ways to communicate information to students regarding the quiz requirement and address questions as they arise, it also offers several ways to deliver the quiz to students, posing an array of ways to differentiate for learners.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Representation

Implementation of weekly quizzes on assigned readings aligns with the UDL Principle I, Provide Multiple Means of Representation. The instructor’s syllabus gives a detailed explanation of the quiz requirement. By listing the total number of pages for each reading assignment, the instructor gives a visual cue for students, which enables them to set aside time for completion of reading assignments based on the length of the required readings. In order to insure that students understand the ramifications for not completing reading assignments, instructors can also take advantage of initial class meetings to outline expectations for students.

Though each student gets a hard copy of the syllabus, Blackboard (the course management system), emailing and face-to-face meetings offer multiple means of communicating information with students. While the syllabus is something tangible, students also have the ability to view reading assignments and/or revisit the course requirements and grading rubric from any computer or mobile device. Students seeking further clarification of the weekly quiz requirement or reading assignments can express concerns to the instructor during face-to-face meetings, via email, video conferencing or over the phone. The various means of communicating with students and alternatives for presenting information pertaining to the quiz requirement ensures that students have a clear description of what the requirements of the course are and can determine how to prepare accordingly.

The multiple ways for accessing information about the quizzes is important, but the quizzes also enable the instructor to highlight the key points or “big ideas” in the assigned readings through wording of questions. When graded quizzes are returned to students they have a “study guide” to use when preparing for upcoming exams.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Engagement

Implementation of weekly quizzes on assigned readings aligns with the UDL Principle III, Provide Multiple Means of Engagement. Quizzes can be formatted multiple ways, enabling the instructor to appeal to diverse learners, and in some cases giving students the option of choosing which questions to answer from amongst those given. Students are empowered to act autonomously in choosing to complete the reading assignments in preparation for the next class meeting and motivated to be persistent at arriving on time for class to avoid missing the quiz. Further, with clear guidelines on the scope of the requirements, students can be mindful of where reading assignments fit into their daily objectives. Well-prepared students, too, are better equipped to make valid contributions to class discussions further encouraging them to make informed decisions regarding how they approach the course requirements.

Instructional Practice

This module covers information about quizzing students to increase compliance with assigned readings, which is clearly linked to two principles of Universal Design for Learning—Provide Multiple Means of Representation and Provide Multiple Means of Engagement.

As you read this Instructional Practice section of the module, consider if this is an instructional practice you might want to adopt for your classes to increase compliance with assigned readings.

Dr. Kane’s Use of Quizzes

Dr. Melinda Kane has not only developed a concise means of communicating expectations with students but successfully implements pedagogical practices which foster increased completion of reading assignments amongst her students. Quizzes, commonly cited as a means of combating students’ tendency to opt out of completing reading assignments (Pecorari, Shaw, Irvine, Malmstrom & Mezek, 2012), play a key part in Dr. Kane’s pedagogy. While quizzes act as a means of reaching all students, they also allow Dr. Kane to “balance it by treating them as adults.” Quizzes, then, become a means of encouraging her students to make the “right academic choices.”

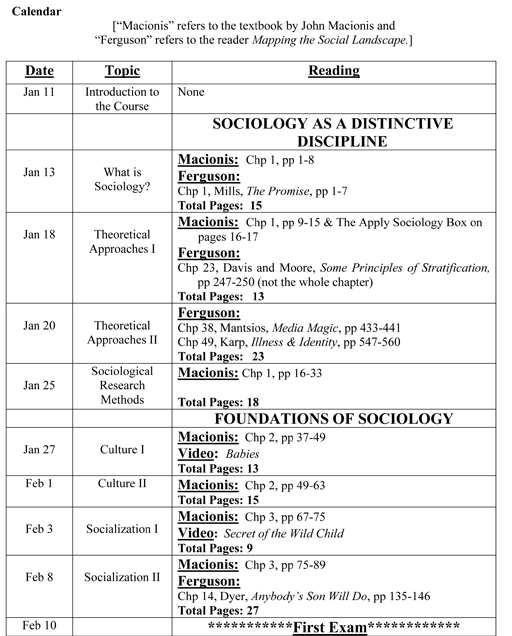

The process of administering quizzes is clearly explained in her course syllabus. The course calendar is broken down with information about all of the course readings. Dr. Kane utilizes the calendar so that students not only know ahead of time that they have a reading assignment, but they are also informed of precisely how many pages they are expected to read and comprehend. Figure 1, below, pictures a portion of Dr. Kane’s course calendar which is included in the course syllabus. The same document is also available as a PDF file. At a glance, students can note which readings are the largest and allot time appropriately for completion of the assignment.

Figure 1: Excerpt from course calendar included in Dr. Kane’s course syllabus. Note how Dr. Kane organizes the calendar, indicating the total number of pages for each assigned reading.

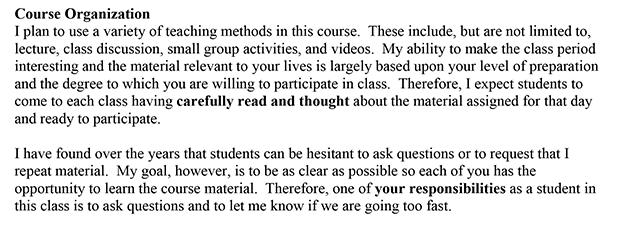

Figure 2: Example of Dr. Kane’s syllabus, outlining expectations for students and specifics about course requirements, including the importance of assigned readings.

Dr. Kane has utilized quizzes to guide student compliance with reading assignments since she began her role as fulltime professor in 2000. Initially, Dr. Kane only used quizzes in lower level courses to help students “form good habits” academically. Since then, she has expanded use of quizzes to higher level courses as a result of requests from students who had previously taken her lower level courses. Students explained to Dr. Kane that they felt they were not “doing as well” in upper division courses without the quizzes in place. This compelled her to make quizzes a standard, across the board in all of her classes.

There are multiple benefits to implementing quizzes as a pedagogical practice. Dr. Kane utilizes quizzes for three reasons. Quizzes compel students to “come to class, come to class on time, and come to class prepared.” Even though Dr. Kane presents materials during class sessions, she likes for students to be able to “take a more active part in class discussions which they cannot do if they have not read.”

Quizzes are given once a week, at the beginning of class. Students do not know which day of the week the quiz will be given. Each quiz focuses specifically on the reading assignment for that day. A total of twelve quizzes are given during the semester, but Dr. Kane only counts ten of the quizzes. This way, students have two quiz grades that may be dropped in the event of an unexpected occurrence. Dr. Kane says she “stresses to students that the drop quizzes should not be frittered away early in the semester.”

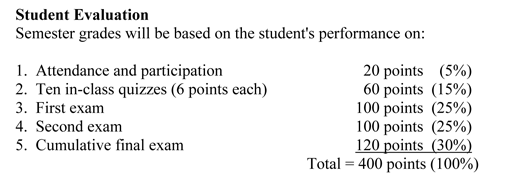

Figure 3, below and the PDF file, shows how the ten quizzes given by Dr. Kane affect the students’ final grade. Quizzes on assigned readings account for 15% of the final grade. This highlights the importance of complying with reading assignments in the course, overall. Students who fail to complete assigned readings place their ability to pass the course at risk.

Figure 3: Outlines how quizzes impact the students’ overall grade in the course.

Formatting Quizzes

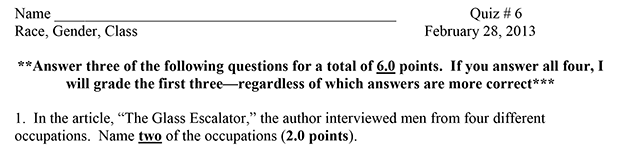

Put into practice, the graded assignments/quizzes which accompany reading assignments may be framed in several different ways. Below, Figure 10, shows an example of a quiz utilized by Dr. Kane with her students. You may also view this document as a PDF file. In this example, students must answer three of four short-answer questions pertaining to the assigned reading. Each question is valued at two points, for a total of six points.

Figure 4: Example of quiz utilized by Dr. Kane to quiz students on assigned readings.

Dr. Kane’s quiz, pictured above in Figure 4, is just one example of how quizzes can be formatted. Still, there are other means of framing quizzes on assigned readings. Some examples of other quiz formats are presented in the following list:

- Monte Carlo Quiz Using the Monte Carlo Quiz method, students know ahead of time that they will be quizzed on readings. However, chance determines when each quiz will be administered, as the roll of a dice determines if a quiz is given. This process results in a quiz being given randomly, making it imperative that students are in class in order to avoid missing a quiz, thus acting as a catalyst in increasing reading compliance and participation in class discussions (Sappington, Kinsey, & Munsayac, 2013).

- Reading Questions In lieu of administering quizzes during class meetings, instructors could implement what Henderson and Rosenthal (2006) refer to as reading questions. After completion of reading assignments, each student is required to compose question(s) that they have about the assigned readings and send them to the instructor via email. Students are encouraged to think critically when developing their questions. Reading questions give instructors an idea of students’ understanding of reading assignments (Henderson and Rosenthal, 2006).

- Reading Assessment Tests (RATS)Some instructors opt to administer RATS in lieu of a quiz. A supplement to assigned readings, RATS consist of open-ended questions which accompany each reading assignment. A graded assignment, RATS aid in increasing reading compliance and guide students through major points of the reading assignments, preparing them to be active participants in in-class discussions surrounding the lecture (Hoeft, 2012).

As noted above, there are multiple ways that instructors may encourage students to complete the assigned readings. Dr. Kane’s students have confirmed through their comments that her practice of weekly quizzes works for them.

Student Comments

Dr. Kane communicates the requirements for completing weekly quizzes on assigned readings up front. Quizzing is an integral part of the course, and students who lack preparation for weekly quizzes gamble with their grade. Overall, students do not complain about the weekly quiz requirement. In fact, student response to the course requirement is largely positive, with students recognizing that quizzes encourage them to come to class prepared, and the quiz requirement helps them learn course material.

One student summarized the impact of Dr. Kane’s weekly quizzes on learning in this way:

“This strategy is effective in my learning experience by helping me to be better prepared for class. Since I never know when the quiz will be I am forced to read all the assigned readings. Although she usually gives the quizzes on Thursday, I always read for Tuesday’s class just to make sure. Since the quizzes are worth a good portion of our final grade I don’t ever want to risk getting a 0 for not reading. Since I read the text the night before and know that I may be quizzed on it I try to grasp the main points.”

Most impressive are the students who proclaim that they enroll in Dr. Kane’s course because of the quiz requirement, since without it they are less accountable for completing assigned readings.

Learn More

Literature Base

Editor’s Note: The Literature Base section of each College STAR module provides a brief summary of support for the Instructional Practice in the module. This is not an exhaustive literature review. It is designed to give the viewer an introduction to the literature about the module Instructional Practice. Please consider using the Learn More section of the module to supplement the information you obtain through this Literature Base summary.

While many educators identify the classroom as central to students’ learning, they also recognize the importance of completing out-of-class assignments (i.e. assigned readings) which enrich the quality of course meetings and discussions. When it comes to completion of pre-reading assignments for collegiate level courses, however, the general trend as documented by research, has become one of noncompliance (Brost & Bradley, 2006). Trudeau (2005) examined the notion that “it is incumbent of instructors to create a structure that encourages and even permits pre-class preparation.” As such, professors must decide what pedagogical practices to employ in an effort to tackle, head-on, a practice that has now become commonplace.

The brief video that follows, “Reading What’s Assigned”, [transcript] (Dunn, 2012) is just one example of what happens to a well-intended class discussion when students fail to comply with reading assignments.

Motivating students to complete pre-reading assignments is not an easy feat; in fact it is a challenge (Trudeau, 2005). According to research, students openly admit little to no reading before class meetings just as the students admitted in the preceding video (Sappington, Kinsey, & Munsayac, 2013). In fact, the number of students who complete assigned readings on any given day amounts to approximately one-third of all students (Brost & Bradley, 2006). Such factors make self-reporting an unreliable means of assessing reading compliance, as students tend to “over-report” such “socially desirable” behaviors (Sappington, Kinsey, & Munsayac, 2013). Noncompliant readers mean less engaged students and class discussions which lack productivity. Still, some professors feel reading is the students’ responsibility and leave it to them. Considering the students’ prospective, the following suggestions would encourage reading compliance (Hoeft, 2012):

- Conduct quizzes

- Give other supplementary, graded reading assignment(s), and

- Utilize course “reminders” to promote interest in reading assignments.

These suggestions align with research findings—as presented by Hilton, Wilcox, Morrison and Wiley (2010)—that many college students are influenced by extrinsic factors when deciding to complete reading assignments. Thus, how the reading assignment is framed becomes a key factor in affecting students’ reaction to the assignment. Research suggests that linking assigned readings with a grade is an ideal way to ensure that students complete their assignments. Association with a grade has the potential to motivate twice as many students to complete assigned readings in comparison to the number of students who read when there is no grade associated with reading assignments. Quizzes give assigned readings another “purpose beyond the fact that it is” a requirement (Hilton, Wilcox, Morrison, & Wiley, 2010).

Henderson & Rosenthal (2006), suggest professors must seize the opportunity to communicate expectations to students early-on. Not only does this set the tone for the course, it also gives students an opportunity to clarify any ambiguous matters as the semester gets started. This insures that both professor and students are on the same page.

References & Resources

Brost, B. D., & Bradley, K. A. (2006). Student compliance with assigned reading: A case study. Journal of Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 6(2), 101-111. Retrieved from http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ854930

http://josotl.indiana.edu/issue/view/150

CAST (n.d.) About CAST: What is Universal Design for Learning. Retrieved from http://cast.org

CAST (2009). CAST UDL online modules. Retrieved from http://www.cast.org

Dunn, E. J. (2012). Reading what’s assigned. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2ZeIqvXVsMc

EnACT. (n.d.) 14 common elements of UDL in the college classroom.

Evans, C., Williams, J. B., King, L., & Metcalf, D. (2010). Modeling, guided instruction, and application of UDL in a rural special education teacher preparation program. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 29(4), 41-48. Retrieved from Education Research Complete

Henderson, C., & Rosenthal, A. (2006). Reading questions: Encouraging students to read the text before coming to class. Journal of College Science Teaching, 35 (7), 46-50.

Hilton III, J. L., Wilcox, B., Morrison, T. G., & Wiley, D. A. (2010). Effects of various methods of assigning and evaluating required reading in one general education course. Journal of College Reading & Learning, 40 (3), 7-28. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ906036.pdf

Hoeft, M. E. (2012). Why university students don’t read: What professors can do to increase compliance. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning, 6 (2), 1-19. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1343&context=ij-sotl

Immordino-Yang, M., & Damasio, A. (2007). We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education, Mind, Brain & Education, 1(1), 3-10. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-228X.2007.00004.x

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-228X.2007.00004.x

National Center on Universal Design for Learning. (2011). About UDL. Retrieved from http://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl

Pecorari, D., Shaw, P., Irvine, A., Malmstrom, H., & Mezek, S. (2012). Reading in tertiary education: Undergraduate student practices and attitudes. Quality in Higher Education, 18 (2), 235-256. doi: 10.1080/13538322.2012.706464 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2012.706464

Rose, D., & Dalton, B. (2009). Learning to read in the digital age. Mind, Brain & Education, 3(2), 74-83. doi:10.1111/j.1751-228X.2009.01057.x

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-228X.2009.01057.x

Rose, D. H., Harbour, W. S., Johnston, C. S., Daley, S. G., & Abarbanell, L. (2006). Universal design for learning in postsecondary education: Reflections on principles and their application. Journal of Postsecondary Education & Disability, 19(2), 135-151.

Retrieved from Education Research Complete.

Rose, D. H. & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum.

Retrieved from http://www.cast.org/

Sappington, J., Kinsey, K., & Munsayac, K. (2002). Two studies of reading compliance among college students. Teaching of Psychology, 29 (4), 272-274.

doi:10.1207/S15328023TOP2904_02

Trudeau, R. H. (2005). Get them to read, get them to talk: Using discussion forums to enhance student learning. Journal of Political Science Education, 1 (3), 289-322.

doi:10.1080/15512160500261178

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15512160500261178

UDLCAST. (2011, October 7). Introduction to UDL [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MbGkL06EU90&feature=relmfu

Additional Resources

APA Style: A DOI primer. (2009). Retrieved from http://blog.apastyle.org/apastyle/2009/09/a-doi-primer.html

CAST: Center for Applied Special Technology. (1999-2013). Retrieved from http://www.cast.org

CrossRef. (2013). DOI Resolver. Retrieved from http://crossref.org

International DOI Foundation. (2012). Resolve a doi number. Retrieved from http://www.doi.org

Weimer, M. (2010). Getting students to read what’s assigned. The Teaching Professor, 1-17.

About the Author

Dr. Melinda Kane

Sociology

East Carolina University