Using Syllabi to Organize Courses

Contents

Introduction

College students appreciate a detailed class syllabus, presented in a friendly manner so that they are encouraged to do their best in the course. Instructors who write syllabi that convey a welcoming tone may motivate students by conveying an expectation of positive outcomes (Slattery & Carlson, 2005). Students also appreciate the way that a thorough syllabus can act as a guide to the course, assisting them in understanding the course objectives, planning for deadlines and completing assignments. This research supported approach is one way that instructors can organize a course to support student learning. In addition to crafting syllabi that meet the needs of students, faculty often include standard sections that may be mandatory at universities or within academic departments A syllabus can take on several concurrent roles. It can act as a self-management tool for students, helping them approach assignments, gauge their success, and assess where they need to invest more effort (Parkes & Harris, 2002).

The syllabus can serve as a permanent record of class rules and policies, which may prevent students from challenging the grading system by saying that course requirements weren’t communicated clearly (Parkes & Harris, 2002). Often, a syllabus functions as a type of informal contract or agreement between faculty and students, defining their respective responsibilities (Davis & Schrader, 2009; Habanek, 2005; Matejka & Kurke, 1994; Parkes & Harris, 2002; Slattery & Carlson, 2005). The syllabus also can serve as a bridge to all learners. A syllabus that provides options for completing assignments so that students can choose a format that plays to their strengths is practicing the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

UDL Alignment

Each College STAR module explains how a particular instructional practice described within the module aligns with one or more of the principles of UDL. This module aligns with each of the principles: Principle I, Provide Multiple Means of Representation; Principle II, Provide Multiple Means of Action or Expression; and Principle III, Provide Multiple Means of Engagement.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Representation

Instructors who provide syllabi in print, via email, or online through a university’s course management system are using more than one method of representation. This aligns with Principle I by using representation to make syllabi more accessible to students overall because the students may choose their preferred method for reading the syllabi.

Creating organization within syllabi also aligns with Principle I when faculty members choose to provide course information in multiple ways within their syllabi. Instructors may incorporate information about their courses by inserting elements such as tables, flowcharts, spreadsheets, symbols and graphics, in addition to the information presented in text. These alternate formats for presenting information in the syllabus can break the flow of reading pages of text and highlight key points about the course, as well as addressing format preferences among students.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression

Instructors who provide options for assignments on syllabi provide a way for students to tackle assignments in the method and form that best fits their learning styles and differences. This assignment option aligns with Principle II since it allows for different ways of expressing understanding. This allows students to use the formats and methods that allow them to excel, providing a learning environment that favors all students.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Engagement

Choices for completing assignments means that students can use various formats, increasing the likelihood that students’ interest will be peaked and that they will learn (CAST, 2012).The ECU faculty profiled in this module also engage their students by explaining the value of the assignments, tying them to real-world applications or necessary skills. Students are considered to be more involved with classwork if they understand its importance. In addition, by providing detail in their syllabi, Drs. Dunn and Schneider set the stage for heightened student engagement in other ways. Providing calendars with information about upcoming topics helps motivate students to be prepared for class. Listing the course objectives may encourage students to reach those learning goals. And by explaining the grading process, faculty will ensure that students are better informed, potentially increasing their engagement with the course.

Instructional Practice

What is an Organized Syllabus that Guides Students?

Syllabi can be used to fulfill a variety of roles, and including more information complements these functions. A syllabus that’s designed to meet student needs makes it easier for them to complete their assignments correctly. It also may prevent students’ misunderstandings about assignments (Hockensmith, 1988; Slattery & Carlson, 2005). A well-organized syllabus provides structure for faculty, as well (Slattery & Carlson, 2005).

It also can be helpful to include information about support services for students. First-year students in particular may be unaware of the resources and services available to them. Including information about support services such as campus tutoring resources, the school’s writing center, and the Disabilities Support Services (DSS) office can prove helpful for students. For example, ECU requires a syllabus statement addressing students’ rights under federal antidiscrimination laws. The school’s Department for Disability Services assists students with disabilities.

Syllabi Acting as Informal Contracts

When syllabi fulfill the role of an informal agreement, sharing attributes with contracts, they describe the responsibilities that lie with students and with instructors. In that capacity, they should be “designed to answer students’ questions about a course, as well as inform them about what will happen should they fail to meet course expectations” (Slattery & Carlson, 2005, p. 163).

For syllabi to act as informal contracts or agreements, certain types of information should be included. Grading criteria should explain how grades are calculated. Providing testing policies and exam formats help students prepare. Other recommended content includes standard fare such as course information and contact information for the instructor, a list of textbooks and readings, and attendance and participation policies. Listing the objectives for the class and a schedule of class activities also is key when creating a syllabus that serves as a contract (Matejka & Kurke, 1994). A hallmark of a strong syllabus is the inclusion of information that prevents misunderstandings (Slattery & Carlson, 2005).

Evaluation Criteria

One of the most important pieces of information to allow syllabi to act as informal contracts is the inclusion of evaluation criteria. It is important that students understand and appreciate the grading process and what is required to earn a specific letter grade. This can be done in a variety of ways. Below are two examples of evaluation criteria used in syllabi from instructors at ECU.

Individual Assignment Evaluation Criteria

Dr. Carolyn Dunn, assistant professor in the Department of Technology systems, includes evaluation criteria for each technical writing assignments as part of her syllabus. She explains

Each assignment will be given to you in writing with specific instructions on how to complete it. It is very important that you carefully follow the instructions for each assignment – not doing so will result in lost points. General evaluation criteria are as follows:

Grade Meets Project Criteria Maintains Appropriate Style & Tone Evidence of Revision & Editing Types of Errors A Outstanding Yes Thoughtful consideration Few & minor B Satisfactory Yes Evident Some usage C Satisfactory Not maintained Some evidence of Some serious usage D Not met Not maintained Little evidence of Serious usage Or many minor errors F Does not meet minimum criteria Lacks any evidence of style or tone No revision or editing Many serious And minor errors

Example of Self-Regulated Evaluation

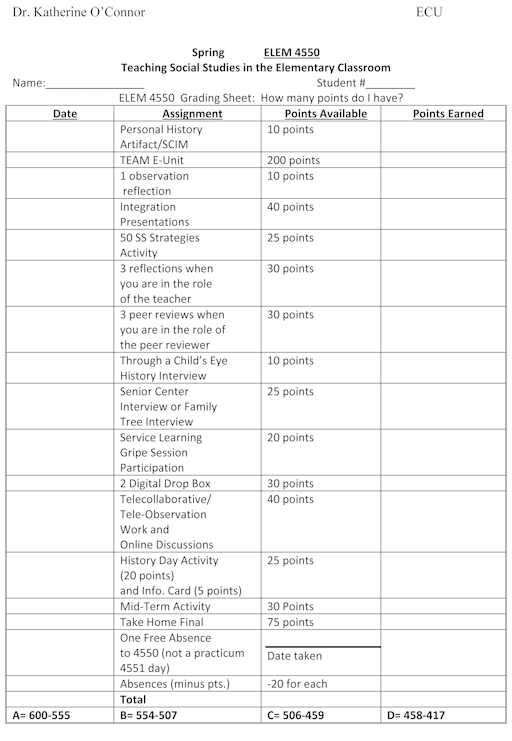

Additionally, faculty may include overall course evaluation criteria and methods to track course progress as part of the syllabus. Dr. Katherine “Katie” O’Connor, an associate professor at ECU, who teaches in the Department of Elementary Education and Middle Grades Education, shared the assignment grading chart that she includes in her syllabi to reduce misunderstandings about grades. Dr. O’Connor says students appreciate the completeness of information she provides by including the grading chart. The self-regulating chart allows students to record information about their academic performance. It also keeps students informed of upcoming coursework.

Dr. O’Connor’s grading chart includes the points associated with letter grades so that students can record their grades and monitor their progress toward the grade they will receive in the course.

“I include this chart in my syllabus so that students have it at the beginning of the semester and we review it as we go over the syllabus,” she says. “The primary purpose is to prompt students to be responsible for monitoring their own progress throughout the semester. Using this chart reduces the potential for misunderstandings about grades.”

Figure 1: chart included in syllabus so that students have it at the beginning of the semester and we review it as we go over the syllabus.

Attendance Policies

Academic Integrity

Syllabi that include policies can informally bind students to that content in a contractual way (Slattery & Carlson, 2005). The document should explain what’s expected of students, along with the consequences for violations (Parkes & Harris, 2002). Dr. Dunn says that laying out the structure of the course and of her expectations means that the consequences for failing to follow a policy are clear. Students understand the ramifications if they plagiarize material. Violations of the student Code of Conduct, including cheating, are discussed. She notes in her syllabus

At a minimum, a “0” will be given for any assignment found in violation of the following Student Code of Contact and a final grade of an “F” may be assigned. The ECU Student Code of Conduct may be found at http://www.ecu.edu/PRR/11/30/01.

Her policy gives parameters, while refraining from taking an absolute approach. A zero-tolerance policy won’t give instructors the opportunity to make adjustments based on their assessment of the situation. There may be educational, cultural, or formatting errors, etc., which are not intentional violations. In such cases, educating the student, along with requiring correction and resubmission, may be the best approach.

Helping Students

Course Calendars for Planning

Informing students in advance about the topics to be discussed can help students prepare for class (Hockensmith, 1988). The individual format that professors chose to use can reflect their areas of expertise. For example, Dr. Douglas Schneider, professor of Accounting, uses Excel spreadsheets to breakdown the course by class meetings. The spreadsheet includes the due dates for homework. He notes

“If the students have a detailed calendar, and we’re looking at it together, they can plan out their studying effort, knowing when they have exams, and knowing when homework is due. And the beauty of it is that students can follow along.”

He includes a comment column, which provides course information and general student reminders. He says this helps keep students “plugged in” to crucial dates for the course and for academics and school events ranging from advising week to drop/add deadlines to homecoming. An excerpt from Dr. Schneider’s calendar is shown below in Table 3.

| Date | Day | Topic | HW Due Date | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8/21 | W | Introduction. Investments. | T 8/20 classes begin | |

| 8/23 | F | Investments. | ||

| 8/26 | M | Investments. | Last drop/add by 5 p.m. | |

| 8/28 | W | Investments. | ||

| 8/30 | F | Investments. | ||

| 9/2 | M | Labor Day - NO CLASSES | 9/3 last day to apply for graduation | |

| 9/3 | T | Leases. | Investments. | State holiday make-up day = MONDAY |

| 9/4 | W | Leases. | ||

| 9/6 | F | Leases. | ||

| 9/9 | M | Leases. | ||

| 9/11 | W | Leases. | ||

| 9/13 | F | Leases. | 9/29 Family Weekend | |

| 9/16 | M | Exam 1, Investments. Leases | Leases. |

Dr. Dunn echoes Dr. Schneider’s commitment to keeping students well-informed by providing a comprehensive syllabus. Providing Key Information

My goal is to really give them as much information as possible up front so that they can then plan,” she says. “And so I really try to alert them to the overall schedule and the overall plan early on so that they can have a handle on what we’re going to be doing for the whole semester.”

In the supplement to the syllabus, she offers details about assignments, explaining the purposes behind the lectures, homework assignments, and explaining that the papers they write will represent different types of workplace documents.

Course Objectives or Competencies

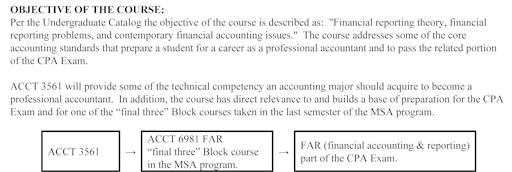

A learning-centered syllabus helps students realize course goals since it provides the course objectives. Dr. Schneider’s approach represents what the authors of The Course Syllabus: A Learning-centered Approach (O’Brien et al., 2008) refers to as setting unit-level objectives. The objectives emphasize his focus on the applicable real-life accounting applications of a given course. He explains that the course will help ready students for the workplace and prepare them to take the CPA Exam. The professor views the objective as an opportunity to explain to students what they are supposed to learn in the course and demonstrate the course’s consistency with its catalogue description. The objective of the course from Intermediate Accounting II is shown below in Figure 10:

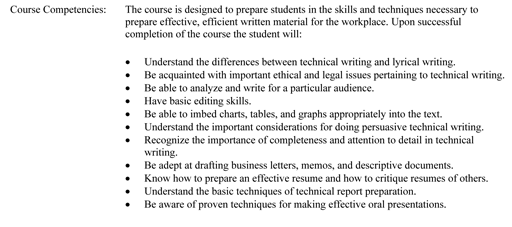

Dr. Dunn lists competencies instead of objectives, focusing more on the skills to be obtained rather than the learning goals to be reached. First, she briefly explains the knowledge the course is designed to impart to students. Then, she uses a bulleted list to give specifics. These include the writing, editing, and oral presentation skills that will be transferable to the workplace. She relies on concrete examples for what the authors of The Course Syllabus: A Learning-centered Approach (O’Brien et al., 2008) refers to as taking the course-level approach. Dr. Dunn’s bulleted list of course competencies, shown below in Figure 11, includes different types of technical documents that students will learn to produce.

Syllabi Presentation

Careful attention needs to be paid to the presentation of the syllabus so that students understand their responsibilities, while also feeling encouraged and welcomed by the instructor. If syllabi are written so that they invite students to take part in collaborative learning, this could attest to the instructor’s interest in the course. This not only shows accountability in keeping with the syllabi’s role as a contract, it also shows the instructor’s commitment (Habanek, 2005).

Thompson’s (2007) observations of teachers revealed that they often strived to make students comfortable in their presentation and in their syllabi. “Teachers devised an array of strategies to welcome students including getting acquainted, being positive, selling the course, and using inclusive language” (p. 58).

Class time spent explaining the syllabi at the start of the semester offers instructors the opportunity to demonstrate their enthusiasm for the course and their interest in seeing students succeed. The discussion of the syllabus is part of the first impression that students form about their instructors. The presentation affords instructors the opportunity to show that while they are concerned about the students’ learning and want to support them, they also are serious about their responsibilities (Thompson, 2007; Parkes & Harris, 2002). As Thompson (2007) states: “Balancing these competing tensions represents one of the most challenging aspects when presenting the syllabus” (p. 55).

Before tackling the syllabus’ policies and requirements, instructors might want to begin by welcoming students to the class (Thompson, 2007). To prevent students from feeling intimidated, instructors can explain that the rules and policies are reasonable and easily complied with by most students. Dr. Dunn emails her syllabus before the start of the semester to her distance learning students so that they understand her requirements and policies. She also posts it on Blackboard.

To counterbalance the syllabus’ more serious content overall, some instructors may project a friendly tone of voice and a demeanor that welcomes students. They may stress areas where students have some control, or they may discuss their love of the subject (Thompson, 2007). Instructors can present themselves as approachable and accessible, while still making their high expectations known.

The use of classroom technology can aid the instructor’s presentation. This can be done with technology that makes the syllabus visible onscreen using Blackboard or software programs, including PowerPoint and Word. Projection helps students follow along more easily and allows instructors to interact more directly with students, and engage their attention (Thompson, 2007).

Summary

Academics realize the value of syllabi as contributing to effectiveness of teaching (Matejka & Kurke, 1994). A strong syllabus helps the students meet the course objectives and keeps them and faculty on track. In addition to offering a clear structure, if it presents the class in a positive light by adopting an encouraging tone, students can view themselves as active participants able to improve their grades (Slattery & Carlson, 2005; Thompson, 2007). A learning-centered syllabus goes beyond traditional expectations. It sets an encouraging tone that promotes learning, communicates the instructor’s commitment to learning, and outlines the responsibilities of faculty and students in support of learning (O’Brien et al., 2008; Parkes & Harris, 2002).

syllabus also can be used to build enthusiasm for the course when it contains information about the purpose and importance of assignments (Hockensmith, 1988; Slattery & Carlson, 2005). Overall, it can be perceived as a reference document that’s packed with pertinent information (O’Brien et al., 2008; Parkes & Harris, 2002).

Researchers have found that extensive detail helps guide students through the course (Habanek, 2005; Slattery & Carlson, 2005). It may act as a plan. It also may provide a type of cognitive map suggesting the route they need to travel on their intellectual journey. Regardless, the syllabus is a concrete representation of the instructor and the course, “a manageable, profound first impression” (Matejka & Kurke, 1994).

The importance of the syllabus is discussed by faculty at a Canadian university in the YouTube video titled “Creating a Syllabus,” [transcript] (University of Saskatchewan, 2013), shown below in Figure 12. In the video, several faculty members describe developing a syllabus that helps students succeed and that welcomes them to the class.

The educators in the YouTube video in Figure 12 advise instructors to consider the information that students want when creating a syllabus. Assignments and the grading process should be explained in detail. This ensures that students know what’s expected of them and the amount of work required by the course. However, the rules of the syllabus need to be tempered by the instructor’s enthusiasm for the course.

Learn More

Literature Review

Researchers have assigned various purposes to syllabi depending upon their design; however, there are standard expectations of content, which are found universally. These include: instructor contact information, course objectives or goals, grading information, and a schedule of assignments (Matejka & Kurke, 1994; O’Brien et al., 2008; Parkes & Harris, 2002; Slattery & Carlson, 2005). More thorough syllabi also may include course prerequisites, disclaimers, and a bibliography of readings (Slattery & Carlson, 2005). The syllabus could address academic freedom, informing students that they need to respect the views of their peers (Parkes & Harris, 2002).

Syllabi, serving in the role of informal contracts, spell out the accountability of the instructor and the students (Habanek, 2005; Parkes & Harris, 2002). It’s not just instructors who support the use of syllabi as contracts. In Davis and Schrader’s 2009 study, where one-fifth of the students fell into the category of the older, nontraditional student, students indicated their preference for contract-style syllabi. The authors of The Course Syllabus: A Learning-Centered Approach suggest considering the following factors when designing a course syllabus: the diverse needs of students, the instructor’s teaching style, and the strategies and assessment used (O’Brien et al., 2008).

A learning-centered syllabus explains course objectives and the process or skills students need to meet those objectives (O’Brien et al., 2008; Parkes & Harris, 2002). This communication of course objectives or goals is a vital component of an effective syllabus (Habanek, 2005; Matejka & Kurke, 1994; Slattery & Carlson, 2005). The syllabus was found to be a significant contributor to the quality of teaching by administrators, professors, and students, according to a survey conducted by Cooper and Cuseo in 1989 (as cited in Matejka & Kurke, 1994).

Despite the importance of syllabi, some researchers point to a scarcity of literature on the impact upon student performance, which they sought to address with their studies (Davis & Schrader, 2009; Parkes & Harris, 2002; Slattery & Carlson, 2005). Parkes and Harris (2002) noted that they relied on professional judgment as the basis for their suggestions on creating syllabi that promote student learning. Slattery and Carlson (2005) added to the literature by providing anecdotal evidence of best current practices for syllabi. They suggest that by giving students a clear indication of the course’s organization, they are better prepared to succeed in their academic journey.

References & Resources

References

Blinne, K. C. (2013). Start with the syllabus: HELPing learners learn through class content collaboration. College Teaching, 61(2), 41-43. doi:10.1080/87567555.2012.708679

CAST (n.d.) About CAST: What is Universal Design for Learning. Retrieved fromhttp://cast.org

CAST (2009). CAST UDL Online Modules. Retrieved from http://www.cast.org

Davis, S., & Schrader, V. (2009). Comparison of syllabi expectations between faculty and students in a baccalaureate nursing program. Journal of Nursing Education, 48(3), 125-131. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20090301-03

http://dx.doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20090301-03

Retrieved from EBSCO

EnACT. (n.d.) 14 common elements of UDL in the college classroom.

Evans, C., Williams, J. B., King, L., & Metcalf, D. (2010). Modeling, guided instruction, and application of UDL in a rural special education teacher preparation program. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 29(4), 41-48.

Retrieved from Education Research Complete

GMCTE U of S [Gwenna Moss Centre for Teaching Awareness]. (2013, March 12). Creating a Syllabus [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mxln5qBDr94

Habanek, D. V. (2005). An examination of the integrity of the syllabus. College Teaching, 53(2), 62-64. doi:10.3200/CTCH.53.2.62-64

Hockensmith, S. F. (1988). The syllabus as a teaching tool. The Educational Forum, 52(4), 339-351. doi:10.1080/00131728809335503

Immordino-Yang, M., & Damasio, A. (2007). We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education, Mind, Brain & Education, 1(1), 3-10. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-228X.2007.00004.x

Matejka, K., & Kurke, L. B. (1994). Designing a great syllabus. College Teaching, 42(3), 115-117. doi:10.1080/87567555.1994.9926838

National Center on Universal Design for Learning. (2011). About UDL. Retrieved fromhttp://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl

O’Brien, J., Millis, B.J., & Cohen, M.W. (2008). The course syllabus: A learning-centered approach. (2nd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Parkes, J., & Harris, M. B. (2002). The purposes of a syllabus. College Teaching, 50(2), 55-61. doi:10.1080/87567550209595875

Rose, D., & Dalton, B. (2009). Learning to read in the digital age. Mind, Brain & Education, 3(2), 74-83. doi:10.1111/j.1751-228X.2009.01057.x

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-228X.2009.01057.x

Rose, D. H., Harbour, W. S., Johnston, C. S., Daley, S. G., & Abarbanell, L. (2006). Universal design for learning in postsecondary education: Reflections on principles and their application.Journal of Postsecondary Education & Disability, 19(2), 135-151.

Retrieved from Education Research Complete.

Rose, D. H. & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum.

Retrieved from http://www.cast.org

UDLCAST. (2011, October 7). Introduction to UDL [Video file]. Retrieved fromhttp://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MbGkL06EU90&feature=relmfu

Slattery, J. M., & Carlson, J. F. (2005). Preparing an effective syllabus: Current best practices. College Teaching, 53(4), 159-164. doi:10.3200/CTCH.53.4.159-164

Thompson, B. (2007). The syllabus as a communication document: Constructing and presenting the syllabus. Communication Education, 56(1), 54-71. doi:10.1080/03634520601011575

Zhong, Y. (2012). Universal design for learning (UDL) in library instruction. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 19(1), 33-45. doi:10.1080/10691316.2012.652549

About the Author

Carolyn Dunn

Technology Systems

East Carolina University

Dorothy Muller

Office for Faculty Excellence

East Carolina University

Douglas Schneinder

Department of Accounting

East Carolina University