Utilizing Contemplative Practices to Balance Brains in Honors Education

Contents

Introduction

This case study examines the use of contemplative practices in an Honors seminar with eleven first-semester students. Honors students are typically strong in verbal, rational, linear, abstract, temporal, rational, and analytic intelligence—their left brains. Students in this course exercise many creative and contemplative practices to strengthen their intuitive, creative, spatial, relational, holistic, unconscious, Gestalt, non-linear, and non-verbal intelligence—their right brains. This includes: visualization, drawing, photography, meditation, and dream analysis. In this context, I refer to right and left-brain intelligence as Bogen (1975, p. 25) and Ornstein (1972, p. 37) have defined these parallel ways of knowing: two modes of consciousness, two types of intelligence, or two cognitive styles.

The Honors College at Appalachian State University typically admits students who are in the top 5-10% of their high school class. High school performance and standardized test scores indicate the high ability and left-brain skills and strength of Honors students. These are high-achieving students who are often also in the gifted education programs. Among high ability Honors students, we are increasingly finding disabilities including: attention deficit hyperactivity disorders, behavioral disorders, or autism spectrum disorders. These students who exhibit both high abilities and learning differences are twice-exceptional (2e) (Yssel, N. Adams, C., Clarke, L.S., and Jones, R., 2014). They are often not identified (Adams, Yssel, & Anwiler, 2012), yet they do not fit neatly into a single category. By virtue of admission into the Honors College, students are placed in the high ability category, but many need support to accommodate their diverse learning styles. Mindfulness skills developed through contemplative practices aligned with the UDL framework is one of many ways to provide support to high ability and diverse learners.

In this Honors seminar titled Balanced Brains: Integration and Visual, Intuitive Intelligence, students learn about and exercise their visual and intuitive intelligence in order to integrate that with their more commonly exercised left-brained intelligence for whole-mind cognition. Working from the foundation of Williams and Newton’s (2007) concept of “omniphasism,” students come to better value, strengthen, and integrate their many forms of intelligence to be “all in balance.” Through this process, students become more creative, better decision makers, more competent problem solvers and, with whole mind synthesis, better able to engage with and contribute to society.

The need for counseling due to behavioral, emotional, mental health concerns has increased across the college student population (Kitzrow 2003) and is important to consider within Honors education. Honors students regularly take heavy and difficult course loads, often pursue double or triple majors, and participate in numerous extracurricular, leadership, and service positions. Many Honors students are perfectionists who hold themselves to very high standards. Perfectionism can have both adaptive and maladaptive outcomes (Wimberly and Stasio 2013). In its adaptive form, it exhibits as high self-esteem and academic performance and in its maladaptive form as psychological disorders like depression and anxiety (Rice et al 2006). Mindfulness skills could provide the needed support and tools for adaptive outcomes and success.

Objectives

In this case study, participants will explore:

- Connections between mindfulness skills and UDL.

- Examples of how contemplative practices can be utilized in an Honors classroom.

- Benefits of contemplative practices and UDL for Honors education.

UDL Alignment

UDL aligns with contemplative practices by presenting learning “through multiple sensory avenues and a variety of conceptual frameworks” (Educause Learning Initiative, 2015). Students in this course learn the following mindfulness skills through contemplative practices: attentiveness, intuition, self-awareness, equanimity, and coping (stress and anxiety reduction). In the below discussion, I highlight how mindfulness skills developed in this course are interconnected with multiple UDL checkpoints primarily in the two following areas.

Multiple Means of Expression

Assignments in this course have optional pathways. Students pick their own subjects, inspiration, and method for completing the exercises. They are offered multiple entry points. For example, they begin many assignments “by relaxing with a contemplative practice of their choosing.” They are encouraged to experiment and try different options and perspectives to see what works for them and what does not.

The navigation and required responses for each assignment are individualized. Each assessment is based exclusively on the student’s reflection of their process (and not what they produce). Each assignment has specific requirements, which allow students to “try” different activities and mediums. In the final Creative Show, students are encouraged to present and discuss however they like. The requirement to communicate what they have learned can be fulfilled through writing, oral presentation, or song, as well as through their work: the creative products they have made throughout the class. Students chose differently and combinations of these options have been represented.

In this course, students physically act, make, and create. It is what they learn from doing that determines their grade, not what they produce. Each activity is interactive or experiential. They are exploring underlying ideas about how brains work through active engagement—by creating, moving, playing, and making. Assignments like the Personal Symbol/s, for example, require them to create an individualized product, but it does not restrict how they do that. It is up to each student to decide what to do to represent themselves: by drawing, painting, coloring, collage, writing, etc.

Multiple Means of Engagement

Self-awareness evolves throughout the course as students come to learn what is easiest/most challenging for them. As they work through the steps of each Creative Assignment, students come to learn the strategies, methods, or contemplative exercises that are most beneficial or rewarding for them. With that understanding, they have tools they can choose to use for self-regulation across the course, other coursework, their academic careers, and lives.

Everyone has a unique learning profile. By utilizing a variety of contemplative practices, this course validates and celebrates that diversity. UDL acknowledges and accommodates that variability and all types of learners, including high abilities, disabilities, and 2e.

The course is highly collaborative. Students are required to create together and share their work. Weekly, students present a show-and-tell of their work and orally discuss their individual reflections of their Creative Activities. From that, they hear about and learn to appreciate diverse approaches and learning styles. They also work collaboratively in class during weekly Set-the-Stage and hands-on brain balancing activities. For the final Creative Show, students collaboratively plan, edit, prepare, set-up and do the show. This is such a novel concept that one semester the students even entitled their show, “It’s Our Show!”

Instructional Practice

Honors Seminars

The Honors curriculum at Appalachian State University includes three topically focused, interdisciplinary Honors seminars (Freshmen-level HON 1515, Sophomore-level HON 2515, and Junior-level HON 3515). Honors students generally complete one seminar a year, followed by their Honors thesis in their senior year. Honors seminars are typically discussion-based seminars that are focused on critical thinking and communication skills. From various disciplinary perspectives, students read texts, write analyses, make presentations, and engage in debates around a common topic.

Bringing UDL to Honors Education via Contemplative Practices

Requirements of this course—exercises conditioning the right brain and working towards omniphasism—are contemplative in nature. Moving beyond the typical pedagogy of Honors seminars described above, this course incorporates UDL checkpoints by means of contemplative practices. In what follows, the course components are described and discussed as examples of how contemplative practices within the UDL framework can be utilized in an Honors classroom.

Set-the-Stage Activity

We begin the course and each class with the Set-the-Stage assignment, a mindfulness activity for centering (balanced, engaged, and optimally present for learning). These are 5-10 minute exercises that include such mindfulness exercises as meditation, coloring, weaving, yoga, nature-mandala making, etc. As the instructor, I start the semester by leading the Set-the-Stage activities for the first 2-3 weeks. Thereafter, the students sign-up for and collaboratively organize one Set-the-Stage assignment during the semester. Students have led such activities as finger-painting, collaborative mandala creations, mindful photo scavenger hunts, friendship bracelet making, etc. By establishing a foundation of mindfulness at the beginning of the semester and at the beginning of each class, students come to see and experience the broad inclusiveness of mindfulness, and its benefits to learning. These activities are often collaborative; even as students are individually exercising mindfulness, they come together to create a final product. Photos below illustrate two Set-the Stage activities.

Figure 1: Set-the-Stage Activity – Students are seated in the grass in a circle creaking a mandala using flowers, leaves and leaves.

Figure 2: Examples of student work

Study of Omniphasism

Building on the foundation of a mindful learning practice established through the Set-the-Stage activities, students read about, discuss, and critically analyze omniphasism (or brain balance) from a variety of disciplinary perspectives. Students read Williams and Newton’s (2007) textbook along with a variety primary texts, which present: the science of brains, differences in learning styles, and inequalities in education systems related to social structures, politics, economics, and history. Additionally, they each read a different ethnographic text, a cross-cultural study. Through these texts, students come to understand the role of educational, social, political, and economic systems in individual brain balance. In our own education system, they come to see a particular type of learning (left-brained intelligence) is valued, while the more creative, intuitive, non-verbal intelligence is de-valued. In this course, the study of omniphasism is also experiential. In each two and a half hour class period, at least 30 minutes is devoted to a hands-on and often collaborative brain balancing exercises. These include Brain Gym (double doodling), and movement (hula hooping, yoga), shown in photos below.

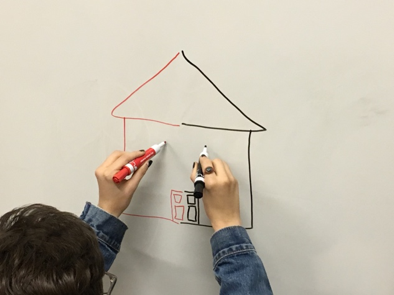

Figure 3: Student is drawing identical on a whiteboard using both hands.

Figure 4: Student is drawing on a whiteboard using both hands. The image the student is drawing is a house. The student is holding a black marker in their right hand and a red marker in their left hand

Figure 5: Students are standing in a circle and playing with hula hoops on a grassy courtyard.

Figure 6: Students are crouching in front of a large wooden board participating in an activity while others are standing around the participants observing their work.

Creative Activities

Outside of class and throughout the semester, students complete thirteen weekly Creative Activities. These generally mimic (with some alterations and additions) the Creative Activities outlined in the Williams and Newton (2007) textbook. Each includes a contemplative activity or activities with a creative product. With these exercises, students are developing their own intuitive, creative, and non-verbal intelligence. This is a new experience for most Honors students who are not expecting to be assigned creative exercises in gifted classes. Below I provide a step-by-step synopsis of each of the fourteen different Creative Activities in the order in which students complete them.

Students read instructions and an example of dream interpretation and then follow that process to interpret one of their own dreams.

In this assignment, students utilize a camera of their choosing (a cell phone is fine or they can check-out an SLR camera) to see through a camera lens and put frames around parts of the real word.

Students make a photo series of something that has never been seen before by combining various objects or people in unconventional places.

For this assignment, students are each paired with another student in the class and instructed to use visual storytelling to communicate “the story” of their partner through the combined use of words and images (photographs).

For this assignment, students create a second personal symbol and compare it to the one they made at the beginning of the semester.

- Creative Visualization In this foundational assignment, students learn to meditate with visuals.

- Step 1: Students spend time reviewing and meditating n visual images from the mediated world, from which they select one to focus on during a concentrated meditation.

- Step 2: After meditating n their selected image, they then describe their visualization experience with images and/or written words.

- Step 3: Finally, they write a reflection discussing how the visual relates to their meditation.

- Personal Symbol For this assignment, students create their own personal symbol.

- Step 1: Finding inspiration from meditation or their dreams, students create a list of significant words that come forth, make notes, and doodle.

- Step 2: Then, they spend time visualizing their personal symbol and write down the dream or draw the symbol that emerges.

- Step 3: In this creative process, they are encouraged to try a variety of different contemplative practices (exercising, dancing, taking a long shower) to access their intuitive minds.

- Step 4: Finally, they create their final symbol with images and/or words as it is best for them.

- Beginning Drawing In this assignment, students begin to learn how to draw.

- Step 1: Students begin by relaxing with a contemplative practice of their choosing (meditation, yoga, mindful walking, etc.).

- Step 2: Then, they make two hand drawings each from one constant angle without moving either their hand or their head position. The second angle must be different or more complex than the first.

- Step 3: Finally, they spend time contemplating their work, with the instruction NOT to be critical but rather to merely note the lines and shapes.

- Drawing II (Contours) In this assignment, students learn to draw contours.

- Step 1: Students begin by relaxing with a contemplative practice of their choosing (meditation, mandala coloring, music, etc.).

- Step 2: Then, they begin drawing their hand without looking at what they are drawing.

- Tip: Students move their eyes slowly from contour to contour until they have drawn their entire hand.

- Tip: They can visualize their pencil touching each contour as their eye moves.

- Step 3: Also for this assignment, students make multiple different Yin/Yang contour drawings modeled after ones presented in the text.

- Step 4: At different stages in the assignment, they are instructed t focus on contours (lines and spaces), and not look at the paper as they draw. Then, in later drawings, they begin to look at their paper as they draw. They learn that if they have trouble focusing on contours instead of features, they can cover part of the drawing with a clean piece of paper.

- Step 5: Between each stage, they contemplate their experience and observe their products while exercising non-judgment.

- Drawing III (Figures) In this assignment, students make two figure drawings, the first one from the text and then another of their own choosing

- Step 1: Students begin by relaxing with a contemplative practice of their choosing (meditation, yoga, music, etc.).

- Step 2: Then. they make a drawing f a figure shown in the text focusing on one contour or space at a time.

- Tip: As they draw if they have trouble staying focused on the area or seeing just the lines, it is suggested that they cover part of the whole drawing with two sheets of paper so only the section they are working on is visible.

- Step 4: Students spend at least 30 minutes n each of two figure drawings.

- Step 5: Afterwards, they contemplate, or “enjoy” their work (by letting go of their inner critic), and reflect on their experience.

- Advanced Drawing This is the culminating hand drawing exercise. The goal of this assignment is for students to produce a drawing of their hand that is a great deal more realistic than their pre-instruction drawings.

- Step 1: Students again begin by relaxing with a contemplative practice of their choosing (meditation, painting, dancing, cooking, etc.).

- Step 2: At this pint, students are able and shift into the integrated-mind drawing mode they have practiced step-by-step in earlier exercises.

- Step 3: They make at least two drawings in two radically different hand positions.

- Step 4: Afterwards, they contemplate their drawings. comparing their earlier drawings to the ones they complete for this exercise. They discuss any insights, developments, and noteworthy experiences during the process.

- Designing Shapes In this exercise, students create meaning with visual forms, black squares.

- Step 1: They begin by creating n a blank page, making three sets of eight 1-inch-square frames on the page.

- Step 2: Form the following concepts they choose three: order, motion, peace, joy, and boldness.

- Step 3: Then, they illustrate the three concepts they selected by drawing four black boxes within each frame, in eight different ways for each concept.

- Step 4: Looking at their final work, they reflect on their experience, speaking to what they felt, learned, and thought about during this process.

- Creative Writing In this exercise students use visual images to inspire creative writing, thereby exploring the visually creative potential of words.

- Step 1: Students select an image and begin by relaxing with a contemplative practice of their choosing (meditation, cooking, yoga, etc.).

- Step 2: While contemplating the image, they write what flows.

- Step 3: As the words flow, they observe to see if they tie together or present a description of what they are feeling or thinking.

- Step 4: Then, they play with the words, rearranging and creating a story or poem.

- Step 5: They follow the process in steps one through four above with a second, different image.

- Step 6: Then, they select a poem and read it silently several times followed by out loud several times.

- Step 7: Finally, they reflect n the entire experience observing the differences between each element. They notice what they learned and their feelings during each step.

- Dream Analysis

- Step 1: To begin, students write down their dream in words.

- Step 2: Then, students relax with a contemplative practice of their choosing (meditation, knitting, coloring, etc.).

- Step 3: Next, they make a list f significant parts of the dream, noting one-to-three words that describe each component.

- Step 4: Fourth, they write clusters of word associations for each of the descriptive words and select the most significant word within each cluster by drawing a circle around it.

- Step 5: They then list all f the significant words and make a parallel list of words associated with some inner part of themselves.

- Step 6: Contemplating their list of inner self word associations, they write a story or interpretation of their dream.

- Step 7: Finally, they reflect n the process and meaning that emerged from the interpretation.

- Photographic Balance

- Step 1: They begin by going to a place that is visually stimulating and spend ten minutes shifting into the intuitive mode (via meditation or another contemplative practice).

- Step 2: After they have made the shift, they spend time looking, seeing, and feeling the environment.

- Step 3: They explore different angles and lighting through the camera lens with one eye shut.

- Step 4: They reflect n how putting a frame around their view affects what they are seeing.

- Step 5: Then, they begin and take at least 24 photographs capturing at least four different subjects, various angles, lighting, and as many different perspectives as possible.

- Step 6: Ultimately, they produce and edit into a visually interesting set of images and words.

- Step 7: They reflect n their final product in light of their process, what they learned, and what they experienced and saw.

- Photo Dream Narrative

- Step 1: They create a visual story about something they care about with the goal of making others care about it, too.

- Step 2: In making their photo series, they are required to use at least one of three different photographic techniques (depth of field, motion, or lighting) introduced in the course.

- Step 3: After contemplating their photo series, they reflect on the storytelling experience and process of completing the assignment. They discuss which f the techniques they chose and how they utilized it specifically in their photographs to tell the story they tell.

- Visual Storytelling

- Step 1: Students begin by meeting and interviewing each other.

- Step 2: They then set a time, and get together to take photographs. They are required to include the following images in their story: close-up portrait, full-body portrait, environmental portrait, photographer-posed portrait, subject-posed portrait, and free shoot.

- Step 3: After editing images, and writing text, they design a visual presentation, a picture, and word story, about their partner.

- Step 4: Finally, they contemplate aspects of the process, including: the interview, photographing, collaboration with their partner, and the layout and design. They write a reflection of what they learned and about their challenges during the process.

- Personal Symbol Re-visited

- Step 1: Finding inspiration from meditating or dreaming, students create a list of significant words that come forth, make notes, and doodle.

- Step 2: Then, they spend time visualizing a personal symbol during a sitting meditation, and write down the dream or draw the symbol that emerges.

- Tip: In this creative process, they are encouraged to try a variety of different contemplative practices (exercising, dancing, taking a long shower) to access their intuitive minds.

- Step 3: Finally, they create their final symbol utilizing images and words however it works for them.

- Tip: They are encouraged to incorporate techniques they have learned throughout the class and developed in previous Creative Activities as they see fit.

- Step 4: Afterwards, they comparatively contemplate their first Personal Symbol (Creative Activity 2) alongside this newest one. They reflect upon what is different, what has changed, and how they felt and feel about both.

Reflections and Assessments

Students reflect upon the process and write an assessment of their experience in doing the Creative Activity. In addition to submitting their written creative work, reflections, and assessment each week, students give an oral report sharing their reflections and assessments in class. The common instructions for all assignments read as follows: Reflect on your own experience [in doing this Creative Activity]. Write a separate assessment of your overall experience. Include an assessment of your experience with each part or practice within the assignment. Explain what you did and experienced in such a way that a friend will understand it. Note what worked or didn’t work for you in this creative exercise. What did you learn? What might you do differently next time?

In specifically assessing each Creative Activity, I require students to discuss their process and do not allow them to discuss or judge their products or creations. I grade the Creative Activities for how they reflect on, write/talk about, and assess what they learned from their process, not for the quality of the product. This “process not product” concept and framework is very difficult for Honors students to understand and accept. These students, who are typically perfectionists, often struggle with the inner critic.

I also require students to include in their assessments an evaluation of their brain challenge, development, and/or balance reached for each aspect of the Creative Activity. For each assignment, I ask them to reflect on and discuss the following: What did it feel like to do this Creative Activity? What, if anything, was difficult? What worked? What allowed you to shift into your intuitive mind? Make it easier for you to get your other coursework done? Helped you relax? Relieved anxiety or stress?) In this Creative Activity, was it challenging or easy to exercise your right brain, get into a zone, or reach omniphasism?

Final Public Creative Show

Students make a public presentation of their work from the class in a Final Creative Show. Students collaboratively peer review and curate their own “art” show, supporting one another in decisions about what to include and how to present their work. The show takes place in a local gallery and coincides with the First Fridays Art Crawl in downtown Boone. In the presentation of this final show, students are required to reflect upon their learning experience of engaging with the many contemplative practices and Creative Activities of the course. Their audience includes many individuals from the community who drop by during Art Crawl, community members from the university and Honors College, as well as friends and family. With all of these individuals, they are required to share, reflect, discuss and further assess their omniphasic learning process. Photos below are from one such Final Creative Show.

Figure 7: Viewers are looking at the works created by students. The work is hung on a white wall on a long wire attached with clips.

Figure 8: People mingling around the final creative show room.

Figure 9: A brochure that one group of students put together for their Final Creative Show

Conclusion: Balancing Brains?

Throughout this course, students work together one-on-one during in-class experiential learning activities, specific weekly Creative Activities, and in the Final Creative Show. These opportunities foster peer mentorship and build community. This seminar is a collaborative learning community in which students support each other. This opens up a space where they experiment with new learning styles and neurodiversity to learn about themselves and grow.

Through this seminar, students gain an appreciation of right-brain intelligence for what it offers—equally valuable strengths and skills to their personal, emotional, and mental well-being. Through contemplative practices, students learn the mindfulness skills of attentiveness, compassion, intuition, self-awareness, equanimity, and coping skills for stress and anxiety reduction. Through the exercise of self-reflection, they gain an awareness of their own individual and unique brains, their right/left brain strengths, and challenges. From that, they learn how to be more, or more often, all in balance. By coming to better understand their own learning styles, they are better prepared to reach their academic and professional goals. Compared to other first-year Honors students who are not exposed to contemplative practices or this seminar, I find these students are relatively more successful in Honors. By participating in Balanced Brains, students are developing and learning tools for academic success.

Honors Colleges are known for nurturing the development of our future leaders, experts across all areas, and those who take on the most prominent positions in society. Yet, are these students who we share the room with today leaders that we want to share the world with tomorrow? As Parker Palmer (2014) expresses, “When I look at the malfeasance of well-educated leaders in business and finance, in health care and education, in politics and religion, I see too many people whose expert knowledge—and the power that comes with it—has not been joined to a professional ethic, a sense of communal responsibility, or even simple compassion” (p.vii). The movement towards building contemplative practices back into the intellectual inquiry arguably offers a corrective approach to this malady.

Learn More

Selection of Ethnographic Texts

Abu-Lughod, Lila (2000). Veiled Sentiments: Honor and Poetry in a Bedouin Society, 2nd Edition. University of California Press.

Cook, Joanna (2014). Meditation in Modern Buddhism: Renunciation and Change in Thai Monastic Life. Cambridge University Press.

Mankekar, Purnima (1999). Screening Culture, Viewing Politics: An Ethnography of Television, Womanhood, and Nation in Postcolonial India. Duke University Press Books.

Mittermaier, Amira (2010). Dreams That Matter: Egyptian Landscapes of the Imagination. University of California Press.

Nakamura, Karen (2013). A Disability of the Soul: An Ethnography of Schizophrenia and Mental Illness in Contemporary Japan. Cornell University Press.

Ness, Sally Ann (1992). Body, Movement, and Culture: Kinesthetic and Visual Symbolism in a Philippine Community (Contemporary Ethnography). University of Pennsylvania Press.

Stoller, Paul (1997). Sensuous Scholarship (Contemporary Ethnography). University of Pennsylvania Press.

References & Resources

Adams, C. M., Yssel, N., & Anwiler, H. (2012). Twice exceptional gifted learners and RTL: Targeting both sides of the same coin. In M. R. Coleman & S. K. Johnsen (Eds.), Implementing RTL with gifted students: Service models, trends, and issues (229-252). Waco, TX: Prufrock.

Bogen, J. E. (1975). Some educational aspects of hemispheric specialization. U.C.L.A. Educator, 17, 24-32.

Educause Learning Initiative (ELI). (2015, April 6). 7 Things You Should Know About Universal Design for Learning, In ELI 7 Things You Should Know. Retrieved from https://library.educause.edu/resources/2015/4/7-things-you-should-know-about-universal-design-for-learning

Kitzrow, M. A. (2003). The Mental Health Needs of Today’s College Students: Challenges and Recommendations. NASPA Journal, 41:1, 167-181

Orstein, R. (1997). The right mind. Making sense of the hemispheres. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co.

Parker, P. (2014). Forward. In D. P. Barbezat & M. Bush (Ed.), Contemplative Practices in Higher Education. San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Rice, K. G., Leever, B. A., Christopher, J., and Porter, J. D. (2006). Perfectionism, Stress, and Social (Dis)Connection: A Short-Term Study of Hopelessness, Depression, and Academic Adjustment among Honors Student. Journal of Counseling Psychology, Volume 53(4), 524-534.>

Williams, R., & Newton, J. (2007). Visual communication: Integrating media, art, and science. New York, London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Taylor & Francis Group.

Wimberley, T. E., & Stasio, M. J. (2013). Perfectionistic thoughts, personal standards, and evaluative concerns: Further investigating relationships to psychological distress. Cognitive Therapy Research, 37, 277-283.

Yssel, N. Adams, C., Clarke, L.S., and Jones, R. (2014). Applying an RTI model for students with learning disabilities who are gifted. Teaching exceptional children. Volume 46(3), 42-52. Council for Exceptional Children.

About the Author

Garrett Alexandrea McDowell

Dr. Garrett Alexandrea McDowell is an Academic Mentor, Honors Faculty, and Director of Communication in the Honors College at Appalachian State University. She holds a Ph.D. and M.A. from Temple University in cultural and visual anthropology, a M.A. from the University of Texas at Austin in photojournalism/visual communication, and a B.A. from Rhodes College in sociology and history. For her dissertation, Dr. McDowell studied the post-1990 return migration of Nikkei (of Japanese descent) from Latin America to Japan and has fieldwork experience in the Soconusco Coast of Chiapas, Mexico, and Lima, Peru. Since 2004, she has taught at five institutions of higher education in multiple departments and states. She teaches a range of courses crossing over anthropology, and visual communication, in addition to multiple interdisciplinary seminars. Since coming to Honors at Appalachian in 2014, she has designed and taught three different Honors seminars: (HON 1515) Balanced Brains: Integration and Visual, Intuitive Intelligence, (HON 2515) Food Fights: Cannibalizing Culture, and (HON 3515) Mind-full and Culture-full. In all of her courses, she incorporates contemplative practices, as well as experiential or service-learning.