Individualized Project-Based Learning: From Theory to Practice

Contents

Introduction

Learning abstract theories can be challenging to students, more so when instructor proximity and simultaneous class interactions are much different in the online class environment. As classrooms and instructional environments continue to evolve, instructors must be more and more intentional about ensuring that students make connections between the actual roles theories play in real life situations.

This case study depicts a project-based learning method to improve student engagement, understanding, and mastery of the abstract theories within the online class environment. An overarching three-stage project was introduced to the students in an online Educational Psychology class, together with detailed project guidelines, grading rubrics, and discussion forums. Students were required to find a problem in their personal /professional life, decide on their project of interest, and apply the theories being presented in the course to solve the problem. Students are tasked with documenting their attempts and effectiveness with their project and reflecting on the learning that occurred during this experience. This project-based learning method will be explained in the context of a motivation class. However, the method can be broadly used across disciplines which involve the teaching of abstract theories.

Objectives

After completing this case study, you will be able to:

- Describe how project-based learning can be utilized to help students comprehend and apply abstract theories.

- Identify possibilities for using project-based learning in your own classroom.

- Make a plan for incorporating project-based learning into your classroom.

UDL Alignment

Each College STAR case study explains how a particular instructional practice described aligns with one or more of the principles of UDL. This case study aligns most with Principle II: Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression and Principle III: Provide Multiple Means of Engagement, while it also aligns with Principle I: Provide Multiple Means of Representation.

Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression

This case study aligns with Principle II: Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression. In particular, I use multimedia for communications with students. When encountering questions, students have the opportunity to email, call, text, or set up a virtual meeting with me. Further, students can post or answer the project-related questions on the “Frequently Asked Questions” forum on the online discussion board interacting with their peers as well. Although I use a checklist, scoring rubric, and student work samples showcasing exemplary work to ensure consistency in quality work, students have multiple ways to express their learning through their individualized projects based on their own unique problems.

Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Engagement

Project-based learning is also an excellent tool for providing Multiple Means of Engagement in a college course. While working on their individualized projects, students are encouraged to participate in the online discussions not only seeking support and help from their peers but also forming communities of learners engaged in common interests or activities. Additionally, I provide students with feedback which focuses on intentions, process, and efforts over the end results. I also provide students who fail to meet the mastery standard with a second chance to make improvements based on the feedback. Further, as part of the project requirement, students are expected to document their progress and reflect upon their learning during the application experience in their project report. The three-stage process of the project allows students multiple ways to engage with the class.

Institutional Practice

Problem Statement

A common problem facing faculty when teaching abstract theories is the waning of student motivation. Some students complain that theories are too abstract, and struggle with seeing how theories could benefit their lives. They do not always seem to see a link between theories and practice in contemporary society. This can be even more challenging in a class offered purely online when simultaneous class interactions with peers and instructors are limited.

To help improve student motivation and engagement, project-based learning has become a popular teaching method in the past few decades (Blumenfield et al., 1991). This instructional practice involves presenting students with a project and challenging them to use the content they are learning in the classroom to accomplish the project. However, this method falls short when students do not really care much about the project, or when there is a lack of support to help students through the process (e.g., Pintrich & De Groot, 1990). To help circumvent the issues with traditional project-based learning, the teaching method was revised in this case study to further improve student motivation, engage student interest and celebrate individual differences in the process of learning: individualized project-based learning. By embracing the UDL principle of Multiple Means of Engagement, I have been able to help students make the most of this learning opportunity.

Individualized Project-Based Learning

As an instruction method that organizes learning around projects that involve having students find challenging problems or issues, design methods to approach the issues/problems, and find solutions based on their newly acquired knowledge of the theories, individualized project-based learning can give students the opportunity to work relatively independently over an extended period of time and to culminate in products aiming to resolve the issues. This method extends beyond traditional project-based learning and can be applied to a variety of disciplines that involve abstract theories with utility values. It allows students to be personally invested in the process, which improves student motivation and learning engagement. Instructors can help students identify related real-life problems of their concern, analyze the problems, and solve them by applying the newly acquired knowledge from the abstract theories.

Project Overview

In this section, I’d like to share how I incorporated the individualized project-based learning (I-PBL) method in my graduate-level educational psychology class focused on a plethora of human motivation theories to enhance student learning, in an attempt to provide you with insight into how you can incorporate I-PBL into your own classes. To help students connect the abstract motivation theories with their real-life problems/concerns in my class, I designed an “Acts of Motivation” (AOM) project that requires them to actively apply the newly acquired theoretical knowledge to their personal/professional lives. The AOM project breaks into two stages: 1) application stage and 2) overall reflection stage. In the application stage, students will have three opportunities to apply three core motivation theories covered in my class over a semester, from which they will choose two based on the theories that they find most interesting and intriguing to further improve student autonomy and motivation in the learning process. And in the overall reflection stage, they will reflect upon the two application experiences as a whole and connect them with the course content in general. If you are teaching a class with abstract theories that could potentially be applied to help solve problems/concerns in real life, you could also design a two-stage project (application and overall reflection) to allow students to use their newly acquired knowledge to benefit their own lives.

Stage 1: Theory Applications

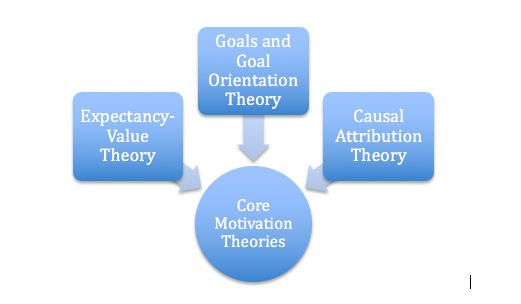

In the application stage, students are required to perform two motivation acts based on the theories of their choices (Figure 1). Particularly, they will identify two motivation issues they encounter in professional/personal life, describe the issues in detail, summarize the two guiding theories from the class, describe the acts they had planned to perform and the impact of their act(s), and the practical implications of this experience.

Figure 1: Core motivation theories in the graduate educational psychology class students could choose from

Questions students will need to answer in the application stage include but are not limited to: What was the motivation issue they encountered? What motivation theory (theories) did they rely on? What act(s) did they perform? When and how did they perform the act(s)? What was the rationale of their act(s) based on the chosen theory? What was the impact? How did these acts make both parties involved feel, etc.? What did they learn from this experience? Students are reminded that they need to tie their acts of motivation back to& the guiding theory of their choice covered in class.

Stage 2: Cumulative Reflections

In stage 2 of this project, students are required to bring the two motivation incidences together, reflect upon them as a whole, and connect them with the course content and their personal journey of learning in this course over the semester. Using what they learned from those two motivation experiences individually, they will prepare a 3-5 page paper summarizing their two theory application experiences. They are instructed to provide deep and thorough reflections regarding what they learned about motivation, connect their experiences with their current or further professions, reflect upon what they learned in the course as a whole, and describe how it will help them become a better educator/professional/sister/brother/daughter/son/parent/colleague/friend, and make concrete plans to further incorporate motivation techniques in their future professional and personal lives.

CRITERIA: The student project report is graded mainly based on the following criteria: 1) The level of understanding of the chosen theory student demonstrate in their summary narrative. 2) The accuracy of their motivation problem statement. 3) The rationale of motivation strategies and methods they used in solving the problem. 4) The connection student made between the theory and practice in the project.

Project FAQ and Content Discussion Forums

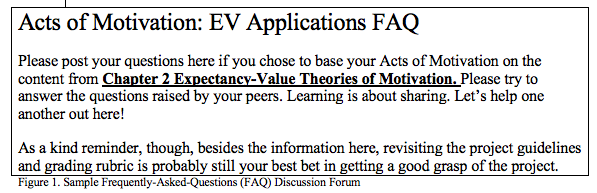

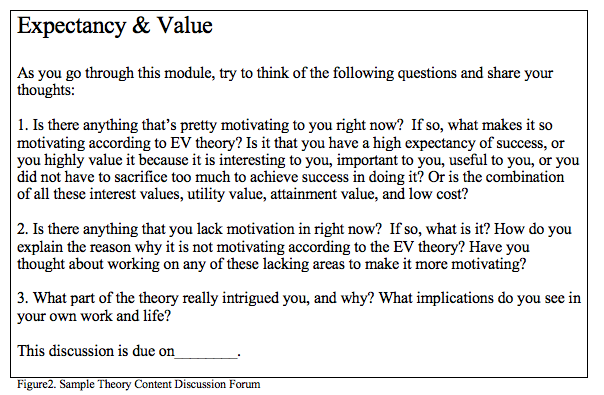

To provide continuous student support and build their competence in accomplishing their projects, Dr. Yang not only provides students with direct email and phone call access but also builds two online discussion forums. The project frequently-asked-questions (FAQ) forum allows students to ask and answer any project-related questions they may have along the way, and the content discussion forums are designed for them to discuss a particular theory of their interest, along with questions and clarifications.

Figure 2: Sample Frequently-Asked Questions (FAQ) Discussion Forum

Figure 3: Sample Theory Content Discussion Forum

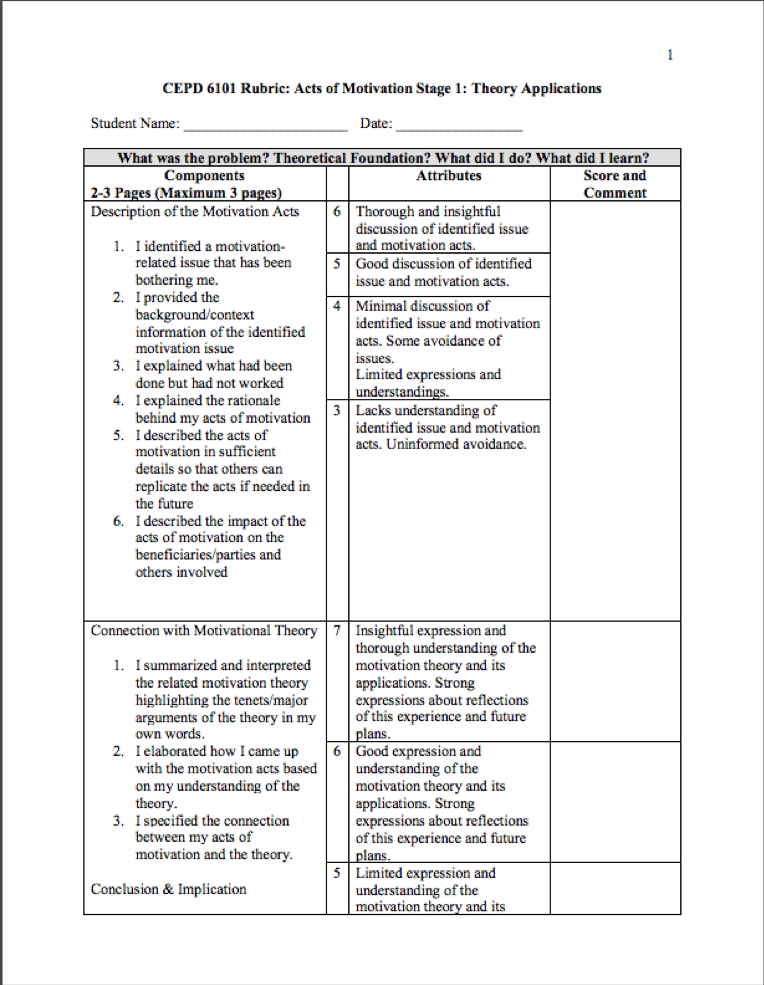

Rubrics

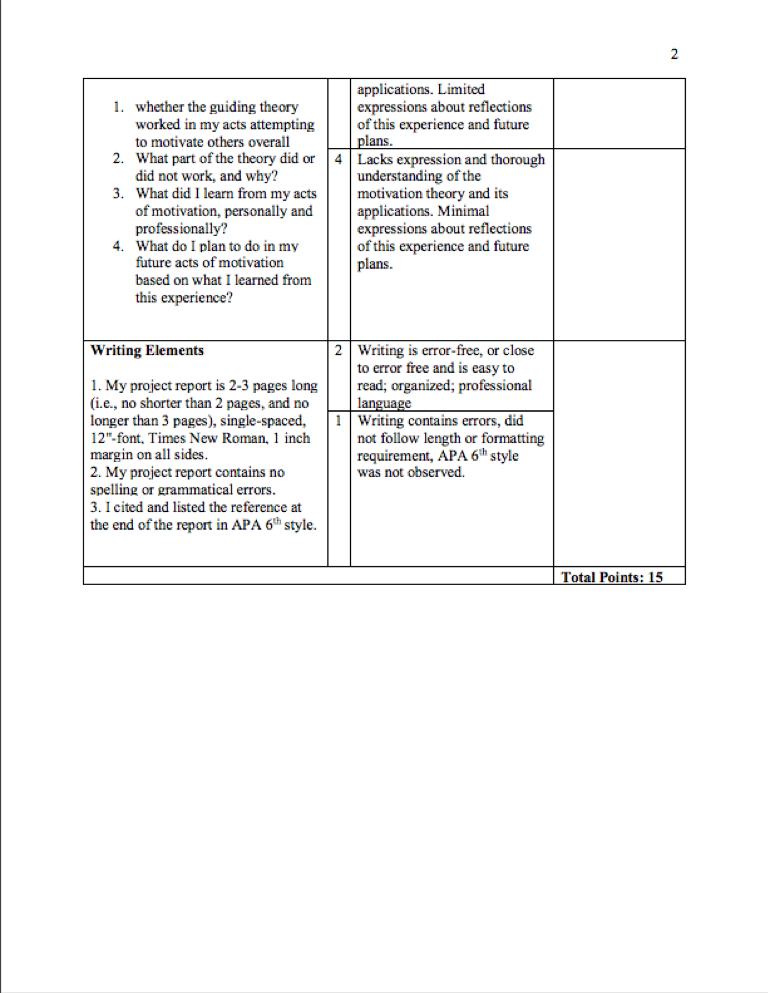

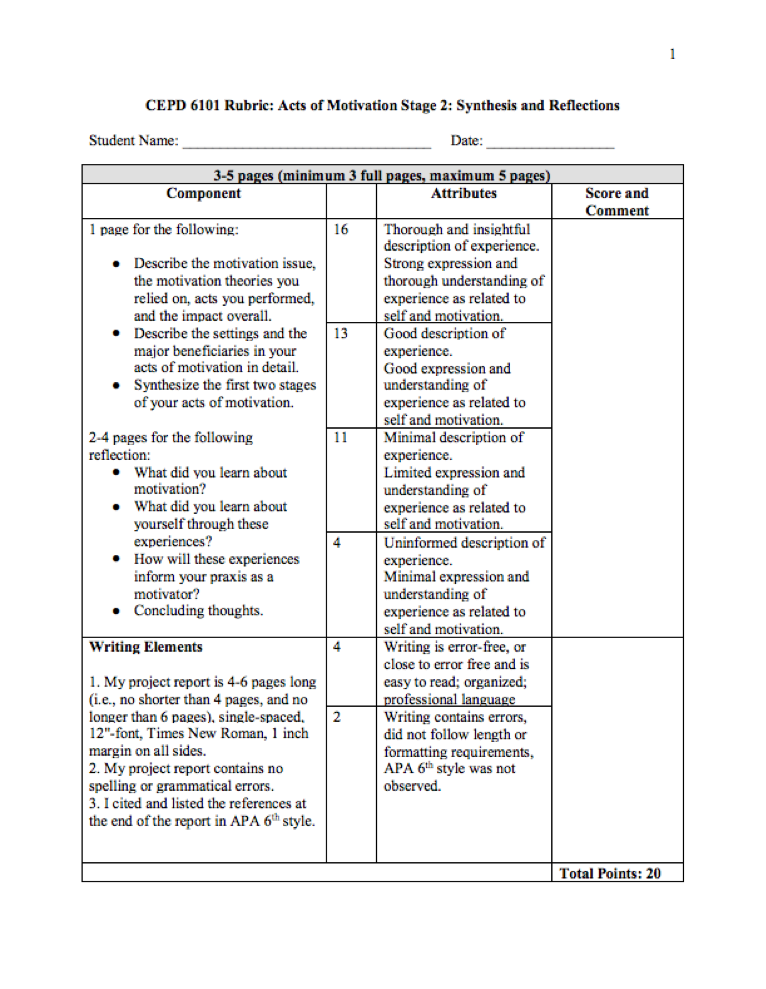

To help students stay on task and increase their chance of success on the project of their choice, grading rubrics of both the application and cumulative reflection stages are provided as follows. The grading rubrics are designed not only to guide students on the steps they need to take in accomplishing their projects but also to remind them of the importance of intentionality and reflection throughout their project.

Figure 4: Stage 1 Project Grading Rubric

Figure 5: Stage 1 Project Grading Rubric (Continued)

Figure 6: Stage 2 Project Grading Rubric

Feedback

The project-based learning method in this course greatly improved student motivation and ability to apply abstract motivation theories to their professional and personal lives. One student said in the feedback anonymously that “The most important thing I learned in this course was the meaning of motivation and what it looks like not only within children but within adults as well. I was able to apply all of the learnings to my personal and professional life as well.” Another student commented that “Application of motivational theories and evaluation of the influences external circumstances have on student’s behavior will assist me in having better control of the classroom.” In my most recent motivation class, 82% of the students reported that they have learned to use the knowledge they gained from this class in their future classes and professions. One student said, “I have already been applying the content from this course in the Instructional Technology I have also been enrolled in. Application of motivational theories will be useful in understanding my own decisions and actions but also those around me. I have learned that it is important to always evaluate a situation before providing my own input. It opened my eyes to some of the mistakes that I made as a first-year high school teacher were avoidable if I had taken a different approach or responded differently.”

Broad Application

Although the case study is in the context of a motivation class, the individualized project-based learning method can be applied to a broad range of disciplines. Finding the utility/practical value of the class content would be the first step an instructor can take in designing the project. The utility value of the course content will allow the instructor to give prompts to students in searching for their own issues or concerns which could potentially be resolved by the new learning the class. By doing this, students will be able to make individual connections with the course content and see how it can benefit them individually. Once the problem is located and refined, instructor support is key to helping students accomplishing the project, which can be achieved in multiple ways from class discussions to emails and individual meetings. Breaking the project down into smaller sub-projects or stages is another key to make it more manageable by students, so they will stay on task and motivated instead of doing minimal work or even quitting. Last but not least, making sure student self-reflection is occurring throughout the process is key to project-based learning. The reflection component can be enforced in multiple ways, such as through project presentations, class discussions, or reflection essays. Allowing students to share their experiences with one another fosters idea-sharing, peer feedback, and potentially increased the impact of project-based learning.

Learn More

As a pedagogy that involves students in applying theories, skills, and techniques to solve real-world problems, project-based learning is a great way to help students see the connection between learning and application. This method has been applied in many disciplines including, but not limited to engineering (Arce et al., 2013), physics (Feder, 2017), chemistry (Davis, Pauls, & Dick, 2017), biology (Regassa & Morrison-Shetlar, 2009), mathematics (Yufrizal, Huzairin, & Hasan, 2017), and environmental education (Genc, M. (2015). It has also been widely used in many other countries such as Korea (Han, 2017), China (Xu & Liu, 2010), and United Arab Emirates (Chowdhury, 2015). Further, as distance learning gains popularity, project-based learning can be a valuable instructional strategy for virtual environments (Jarmon et al., 2008; Márquez Lepe & Jiménez-Rodrigo, 2014).

Project-based learning has also shown promises related to improving student outcomes such as: students’ self-directed learning skills (Bagheri, Ali, Abdullah, & Daud, 2013), life skills (Wurdinger & Qureshi, 2015), self-efficacy, and achievement (Mahasneh & Alwan, 2018). Further, Leh (2014) asserted that it is also found to be a great way to support diverse learners. Although project-based learning has been around for quite some time, it continues to offer potential for instructors to help students engage with abstract course content in ways that are practical and personally relevant. If done well, this can be one way professors can infuse the principle of Multiple Means of Engagement into the college classroom and promote student learning in online class environments.

References & Resources

References

Akhand, M. M. (2015). Project Based Learning (PBL) and webquest: New dimensions in achieving learner autonomy in a class at tertiary level. Journal of Pan-Pacific Association of Applied Linguistics, 19(2), 55–74.

Arce, M. E., Míguez-Tabarés, J. L., Granada, E., Míguez, C., & Cacabelos, A. (2013). Project-based learning: Application to a research master subject of thermal engineering.Journal of Technology and Science Education, 3(3), 132–138.

Bagheri, M., Ali, W. Z. W., Abdullah, M. C. B., & Daud, S. M. (2013). Effects of project-based learning strategy on self-directed learning skills of educational technology students. Contemporary Educational Technology, 4(1), 15–29.

Balanescu, R.-C. (2015). The project-based learning in the higher education – theoretical and practical aspects. Proceedings of the Scientific Conference AFASES, 1, 159.

CAST. (2011a). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.0. Retrieved from http://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl/udlguidelines

CAST. (2011b). UDL guidelines version 2.0. principle I. provide multiple means of representation. wakefield, MA: Author. . Retrieved from http://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl/udlguidelines/principle1

CAST. (2011c). UDL guidelines version 2.0. principle il. provide multiple means of action and expression. wakefield, MA: Author. Retrieved from http://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl/udlguidelines/principle2

CAST. (2011d). UDL guidelines version 2.0. principle III. provide multiple means of engagement. Retrieved from http://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl/udlguidelines/principle3

CAST. (n.d.). About CAST: What is universal design for learning. Retrieved from http://www.cast.org/udl/index.html

Ching, Y.-H., & Hsu, Y.-C. (2013). Peer feedback to facilitate project-based learning in an online environment. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning (Vol. 14, pp. 258–276).

Chowdhury, R. K. (2015). Learning and teaching style assessment for improving project-based learning of engineering students: A case of United Arab Emirates University. Australasian Journal of Engineering Education, 20(1), 81.

Davis, E. J., Pauls, S., & Dick, J. (2017). Project-based learning in undergraduate environmental chemistry laboratory: Using EPA methods to guide student method development for pesticide quantitation. Journal of Chemical Education, 94(4), 451–457. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.6b00352

de los Santos, D. M., Montes, A., Sa, Nchez-C. A., & Navas, J. (2014). Sol-Gel application for consolidating stone: An example of project-based learning in a physical chemistry lab. Journal of Chemical Education, 91(9), 1481–1485. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ed4008414

Feder, T. (2017). College-level project-based learning gains popularity. Physics Today, 70(6), 26–31.

Genc, M. (2015). The project-based learning approach in environmental education. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 24(2), 105–117. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2014.993169

Han, S. (2017). Korean Students’ attitudes toward STEM project-based learning and major selection. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 17(2), 529. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2017.2.0264

Hao, Q., Branch, R., & Jensen, L. (2016). The effect of precommitment on student achievement within a technology-rich project-based learning environment. TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, 60(5), 442–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-016-0093-9

Harmer, N., & Stokes, A. (2016). “Choice may not necessarily be a good thing”: student attitudes to autonomy in interdisciplinary project-based learning in GEES disciplines. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 40(4), 531–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2016.1174817

Jaime, A., Blanco, J. M., Domínguez, C., Sánchez, A., Heras, J., & Usandizaga, I. (2016). spiral and project-based learning with peer assessment in a computer science project management course. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 25(3), 439–449. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10956-016-9604-x

Jarmon, L., Traphagan, T., & Mayrath, M. (2008). Understanding project-based learning in second life with a pedagogy, training, and assessment trio. Educational Media International, 45(3), 157–176.

Laura B. Regassa, & Alison I. Morrison-Shetlar. (2009). Student learning in a project-based molecular biology course. Journal of College Science Teaching, (6), 58.

Lee, J. S. 1. jslee@uindy. ed., Blackwell, S. blackwells@uindy. ed., Drake, J. jdrake@uindy. ed., & Moran, K. A. 1. kmoran@uindy. ed. (2014). Taking a leap of faith: Redefining teaching and learning in higher education through project- based learning. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 8(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1426

Leh, A. (2014). Using project-based learning and google docs to support diversity. International Association for Development of the Information Society (p. 10). International Association for Development of the Information Society.

Mahasneh, A. M., & Alwan, A. F. (2018). The effect of project-based learning on student teacher self-efficacy and achievement. International Journal of Instruction, 11(3), 511–524.

Márquez Lepe, E., & Jiménez-Rodrigo, M. L. (2014). Project-based learning in virtual environments: a case study of a university teaching experience. RUSC: Revista de Universidad y Sociedad Del Conocimiento, 11(1), 76.

Nation, M. L. (2008). Project-Based learning for sustainable development. Journal of Geography, 107(3), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221340802470685

Papanikolaou, K., & Boubouka, M. (2011). Promoting collaboration in a project-based e-learning context. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 43(2), 135–155.

Redkar, S. (2012). Teaching advanced vehicle dynamics using a project based learning (pbl) approach. Journal of STEM Education: Innovations and Research, 13(3), 17–29.

Sulisworo, D., & Santyasa, I. W. (2018). Maximize the mobile learning interaction through project-based learning activities. Educational Research and Reviews, 13(5), 144–149.

Turgut, H. (2008). Prospective science teachers’ conceptualizations about project based learning. Online Submission, 1, 61–79.

UDLCAST. (2011). Introduction to UDL. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MbGkL06EU90&feature=relmfu

Wilhelm, J., Sherrod, S., & Walters, K. (2008). Project-based learning environments: Challenging preservice teachers to act in the moment. Journal of Educational Research, 101(4), 220–233.

Wright, R. K. (2018). Setting them up to fail: The challenge of employing project-based learning within a higher education environment. Event Management, 22(1), 99.

Wurdinger, S., & Qureshi, M. (2015). Enhancing college students’ life skills through project based learning. Innovative Higher Education, 40(3), 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-014-9314-3

Xu, Y., & Liu, W. (2010). A project-based learning approach: A case study in China. Asia Pacific Education Review, 11(3), 363–370. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12564-010-9093-1

Yufrizal, H., Huzairin, & Hasan, B. (2017). Project based-content language integrated learning (clil) at mathematics department Universitas Lampung. English Language Teaching, 10(9), 131–139.

About the Author

Yan Yang

Dr. Yan Yang has over 20 years of cross-cultural teaching experience spanning from elementary to graduate levels. Prior to coming to the U.S. in 2005, she taught English as a second language for six years at Southwest Jiaotong University in China. Dr. Yang is currently Associate Professor in Educational Psychology at the University of West Georgia. She mainly teaches courses in educational psychology and conducts research in human motivation at both undergraduate and graduate levels. Dr.Yang can be reached at yyang@westga.edu.