Using Organization to Streamline Courses

Contents

Introduction

College students give high marks to faculty who organize their classes so that students are well-informed about all aspects of the course including the assignments.

At East Carolina University (ECU), two of the professors lauded by students for creating highly organized courses use different approaches to achieve the same goal: delivering content clearly and consistently to help students succeed. Dr. Douglas Schneider, an accounting professor, has developed his own materials over the years, culminating in photocopied “textbooks”—lecture packets for the course that work in conjunction with the rest of the coursework.

Dr. Carolyn Dunn, an assistant professor who teaches technical writing in the Department of Technology Systems, delivers coursework online in folders, which are posted weekly. Each folder contains a PowerPoint on that week’s lecture. It also includes instructions for a writing assignment, accompanied by an example to help students get started. Students in distance-learning classes receive an extra component—the lecture delivered as a video.

By organizing courses so that students understand what’s expected and are better able to navigate the course, and by presenting lectures in a clear manner, professors help create an environment that’s conducive to learning (Carroll & O’Donnell, 2010). By organizing their courses effectively, Drs. Dunn and Schneider help boost student learning. One research study indicated that university students rank organization as one of the most important traits faculty can possess (Boex, 2000).

UDL Alignment

Each College STAR module explains how a particular instructional practice described within the module aligns with one or more of the principles of UDL. This module aligns with all three principles: Principle I, Provide Multiple Means of Representation; Principle II, Provide Multiple Means of Action or Expression; and Principle III, Provide Multiple Means of Engagement.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Representation

Instructors who create highly organized courses often provide content using more than one method, including distributing print copies, sending emails, or posting it online via the university’s course management system. This aligns with Principle I since different means of representation are used, allowing students to choose their preferred method of accessing information.

Achieving organization requires the mastery of consistency, delivering content in a standard format. Whether course material is available in a textbook format or via online folders, students understand that particular formats will be used for presenting particular types of content. Using technology to project text onto a screen and then highlighting key concepts, instead of simply distributing copies, illustrates another way of providing more than one type of representation. By using advanced organizational tactics, including technology, representation takes more than one form, in keeping with Principle I.

Instructors also may encourage students to complete assignments using the format that is most comfortable for them, submitting their work in print, or as an audio or video assignment. This illustrates the use of Principle I since a choice of representations is offered.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Action and Expression

Instructors who opt to give student choices for completing assignments allow them to take actions that promote student expression. By allowing students to decide upon completing an assignment either verbally, orally, or through graphical or technological means, they are helping students to express themselves by using the best method for their learning styles and differences. Providing assignment options aligns with Principle II since it allows for different ways of expressing understanding. This encourages students to engage in learning.

Module Alignment with Provide Multiple Means of Engagement

Students may become more engaged with the course when instructors allow them to choose their preferred form for completing assignments. In addition, when the practical aspects of the assignments are explained so that their applicability to actual workplace tasks is realized, students may take the coursework more seriously. Drs. Dunn and Schneider assign work that has a clear connection to the working world. In addition, they provide content in an organized fashion that makes it easily accessible and understandable to all students. Grading rubrics are included so that students understand what is required to meet course objectives and earn their desired grades. Drs. Dunn and Schneider also use technology to engage students. Dr. Dunn provides PowerPoints of lectures and students in distance learning courses received videotaped lectures she creates using webcam and Tegrity® software. Dr. Schneider uses an imaging program to project scanned pages from his textbook lecture packets onto a screen so that he can write on those pages, working out accounting problems in class. All of these methods align with Principle III since they serve to engage students in the learning process.

Instructional Practice

This module covers information about well-organized courses which are clearly linked to Principles I, II, and III of Universal Design for Learning–Provide Multiple Means of Representation, Multiple Means of Action and Expression, and Multiple Means of Engagement.

It discusses the importance of organized courses as a method for helping students learn and stay on track with coursework. Organization is considered important by students and faculty alike. In one faculty study, it was perceived as a component of effective teaching.

What is an Organized Course that Guides Students?

The organizational skills of Drs. Dunn and Schneider have been noted by students who say such tactics help them do well in the course. In general, students in research studies report that professors who used organization as a college teaching strategy helped them reach academic success. Research shows that faculty who present material is a clear and logical manner aid student understanding. Faculty efforts to organize content is one way to help student succeed (Feldman, 1989).

Drs. Dunn and Schneider use different organizational techniques but they each provide students with well-organized content. Dr. Dunn creates online folders, divided by types of information. In addition, weekly folders are posted with that week’s work. All folders are found in one location on Blackboard, the campus course management system. Dr. Schneider wrote his own “textbooks” or lecture packets for his courses. Accounting problems to be solved during class are included in the packets. The related material, consisting of homework and practice exam questions, is posted online regularly. After students attempt these problems, Dr. Schneider solves them during class.

The value of organization in boosting student learning is described by Carroll & O’Donnell (2010). “Faculty must give attention to course organization; provide clear class presentations and challenging questions. They must also be responsive to students and listen to them. All of these behaviors create a supportive and encouraging learning environment” (p. 65).

Providing “Clarity and Continuity”

This module focuses on the techniques used by Drs. Dunn and Schneider to organize their courses. There are various definitions of course organization. As an effective teaching strategy, it can encompass everything from the way the instructor plans course content or conducts the class to the way that assignments and exams are structured.

At ECU, students noted that these two professors were adept at using organization to make classes easier to navigate. These students consider their instructor’s course organization skills as a factor in their academic success. The research literature bears this out, indicating that students benefit from organized courses.

Dr. Schneider says his approach is to provide “clarity and continuity” to his accounting students “in regard to the presentation of the lecture material, and the homework.” He uses packets of information that resemble self-published accounting textbooks to provide students with coordinated materials. He considers his approach to be the best way of guaranteeing that students receive the practical instruction that translates to the workplace.

Dr. Dunn standardizes all of her material using the same format, practicing the technical writing skills that she’s teaching. Her assignments for her Technical Writing courses are similar to those that students might encounter in the workplace. She also organizes her courses by releasing course material online according to a schedule. She purposely makes her expectations clear to students and provides them with continuity so that there are fewer misunderstandings and students can be successful.

While they may have similar philosophies in terms of using organization to help students follow the blueprint for their courses, Drs. Dunn and Schneider tailor their methods specifically to fit their content.

Explaining Assignments

The topics listed on the course calendars provided by Drs. Dunn and Schneider, along with syllabi materials, keep students informed about the content of upcoming lectures and assignments. Assignments are chosen that will reflect real-world work duties and tasks. Choosing assignments that have obvious value to the students helps motivate them (Hockensmith, 1988; Slattery & Carlson, 2005).

Dr. Dunn’s technical writing assignments represent different types of workplace writing. In the supplement to the syllabus, she provides detailed information about the coursework so that students understand its purpose. Instructions are provided for all assignments. Examples also are given so that students have a model to follow.

In Dr. Schneider’s accounting courses, students understand that his lecture problems will be similar to the homework problems, and will lead to similar exam questions. Accounting problems are either examples of accounting practices in the workplace or examples of questions like those that will be encountered on the Uniform Certified Public Accountant Examination.

A “Textbook” Approach

Dr. Schneider tailor-made his accounting courses to meet his requirements by writing his own self-published “textbooks” or lecture packets for undergraduate- and graduate-level courses. Each packet contains exercises that will be solved in class and that are synchronized to homework assignments, and to the practice exams and exams. By dedicating himself to the years-long process of writing this material, he’s ensured that the information he considers essential is covered. The packets’ content reflects exactly what he wants to teach. He didn’t do it for profit; he did it to perfect course content. Students buy the packets at the campus bookstore, paying only for the actual cost of photocopying the pages.

These textbook packets help Dr. Schneider streamline his courses, organizing them to maximize student learning. Course content is laid out to promote understanding, according to his tried-and-tested classroom experience. The accounting concepts Schneider teaches in the classroom are reinforced through the related homework assignments and the associated exams. The textbook packets, along with assignments and the exams, correspond to the knowledge that’s tested on the CPA exam, as well as to real-world accounting applications. “And I write all the material; it’s copyrighted by me, and I provide a lot of different ways in which I try to provide a framework for students to understand and learn, and have things organized with graphic presentations,” he says.

The textbook packets also represent the most up-to-date information in the field. Dr. Schneider keeps his textbook packets current. “I rely on a huge number of files that are from newspaper articles or on the Internet that discuss why some of these issues are important and how it relates to the real world and the business world, so I incorporate real-world examples with my actual lecture notes,” he says. “Also, if the accounting regulations have changed, I would take a press release like this and I’ll highlight the press release and try to show how some of what we’re talking about is a very active issue.”

Exercises from the textbook packet are solved during class. Homework and practice exams are posted online using Blackboard, the campus course management system, so that students can print them and work on the problems ahead of class.

Projected Exercises

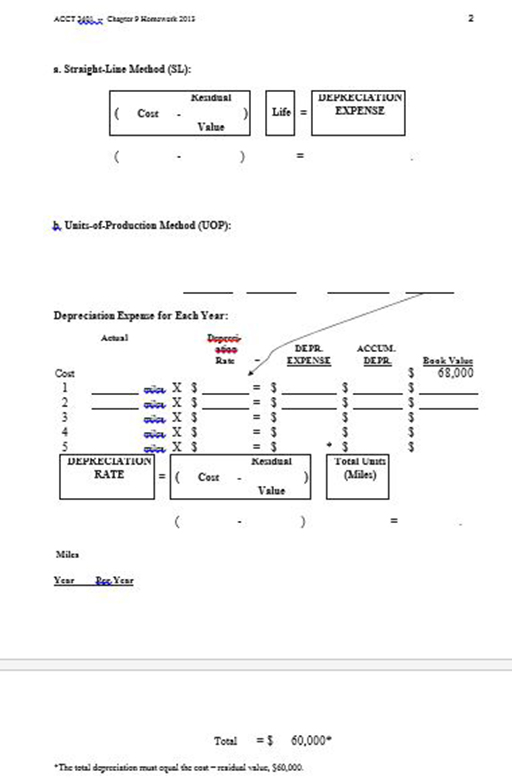

Dr. Schneider uses an imaging program that allows him to scan pages of exercises from the lecture packet so that they can be projected onto a screen and written on during the lecture to highlight key material. Students observe him circling pertinent material and drawing lines to show the relationships inherent to accounting. This method has proven to be an effective learning strategy for students. For every topic, there are several exercises. Figure 1 below is an excerpt showing two of the homework problems on one of the depreciation exercise sheets taken from an undergraduate financial accounting course.

Figure 1: These unsolved homework problems shown above ask students to solve depreciation problems using a straight-line method and a units-of-production method.

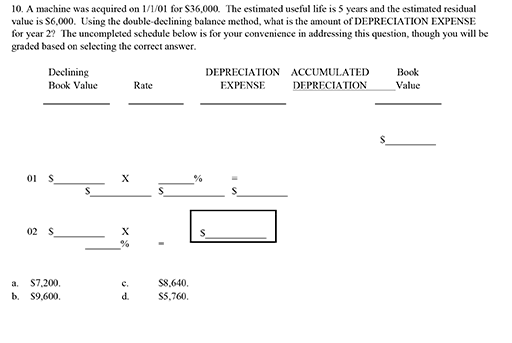

For each topic, the homework problems are the same type of problems as the ones that were explained and solved during the lecture. Dr. Schneider explains that while the numbers have been changed, the framework is the same as it was for the lecture problems. Dr. Schneider provides practice exams in advance of the actual tests. Again, the questions are similar to the lecture and homework problems in keeping with his commitment to “clarity and consistency.” Figure 2, shown below, is one of the questions about depreciation from an undergraduate financial accounting course provided on a practice exam.

Figure 2: The above question from a practice exam asks students to solve a machinery depreciation problem.

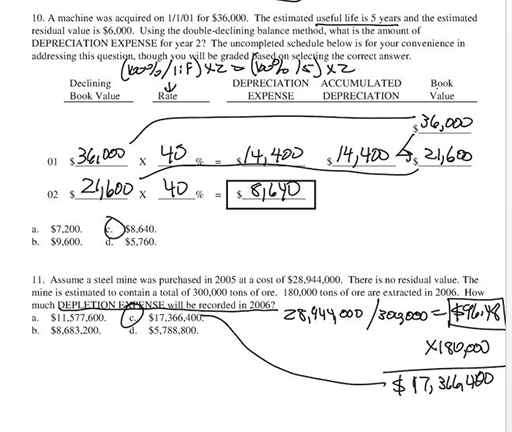

Using imaging software during class, Dr. Schneider works out the answers to problems from the practice exam, including the question on depreciation of machinery shown above in Figure 2. The solved problem is shown below in Figure 3.

Figure 3: The solved question shown in Figure 2 appears above. Dr. Schneider worked out the problem and drew circles and arrows to show the relationships so that students could follow the process.

Dr. Schneider has developed an organized approach that students can follow by using the coordinated material provided in his textbook packets. Some of his students consider the course to be a model of organization. The right approach for creating an organized course, however, will vary between faculty members and will also be driven by the subject being taught. Dr. Dunn’s technical writing class uses weekly folders of content to help students keep track of what’s required from them for that week. She gives writing assignments with specific instructions and an example, and she provides an example of a correct assignment after assignments have been submitted.

A Well-Designed Approach

Dr. Dunn steers students towards a more organized start in her courses using organizational techniques. She produces standardized material to keep her face-to-face and distance learning courses on track. Dr. Dunn starts with a series of folders posted to Blackboard. “Essentially what I do is create a (folder) shell that is then replicated across every section” with additional folders, she says. Each folder contains a different type of information. “So you have the announcements, then you have the syllabus, then the instructor’s information, which has my office hours and all those things, and then I have a section (folder) for weekly modules, and this is for both my face-to-face and online sections,” Dunn explains. On the first week of class, students in each course receive an introductory folder to acclimate them. This folder is formatted as a FAQ containing the anticipated Frequently Asked Questions. It includes the answers to expected queries such as, “What can I expect from the course?” and “What should I know about succeeding in this course?”

Once the introduction folder has been reviewed, students are ready to begin using their weekly folders. Each folder contains all of the material students need for that week, including a PowerPoint explaining the topic and that week’s assignment. Distance learning students receive their PowerPoint presentation online on Mondays. Students in her face-to-face courses receive their PowerPoint lectures on Friday after classes have concluded for that week so that they won’t attempt to substitute the slides for class attendance. For Dunn’s distance learning courses, the weekly folder’s content differs slightly since these students receive video-recorded lectures created using Tegrity (a cloud-based software) each Monday.

Along with the weekly assignments, Dr. Dunn provides an example to guide students. Each week students use the online drop box to submit their assignments for grading. Dr. Dunn returns their assignments within a week. Along with the corrected work, she provides an example of a correct assignment. This organized procedure of providing an example with the assignment, followed by a correct example after the assignment’s submission date, has proven to be an effective learning strategy for her students.

Design Consistency

Dr. Dunn uses these weekly folders to keep her students on track. She says that keeping everything together in one location on Blackboard means her students don’t have to search for documents in more than one place. Her system is a model of organization, according to students.

The weekly set of PowerPoint slides are all similar in appearance, created with the same design elements. This practice demonstrates design consistency to Dr. Dunn’s students, which is one of the hallmarks of good technical writing. Consistent design is one way to make a document stand out and make it immediately identifiable by type or by purpose. The students recognize the format and understand what type of document they have been given.

Distance learning “extras”

Students enrolled in distance learning courses gets extras like a link to that week’s online discussion board so that they can post comments for the group to view and so their classmates can respond with their own posts. The online lecture video via Tegrity included in their weekly folder helps put them on par with students enrolled in the face-to-face lecture courses.

The Tegrity lecture shows students either an image of Dr. Dunn or a computer screen on which she demonstrates an aspect of technical writing as they listen to the audio recording of her narration. This technology records synchronized audio, video and the computer screen. For example, one Tegrity lecture on conducting research features Dr. Dunn walking them through the process. “We use an example about how to critically analyze Internet sources and I use a website. So I actually go to the website and walk them around the website and show them what the problems are with that particular website. So really anything you can pull up on your desktop, you can embed them into the Tegrity lecture,” Dr. Dunn explains. “…They’re watching me; they’re hearing me. If I’m using any links, they’re embedded in there.”

Dr. Dunn also makes use of Tegrity lectures when face-to-face courses are cancelled due to inclement weather or another sort of emergency. Students who have a valid reason for missing a face-to-face class also could be granted access to the Tegrity lecture for that week.

Learning Styles

Dr. Schneider uses effective teaching strategies that accommodate different student learning styles. Realizing that many of his students are unaccustomed to accounting concepts, much of which has to do with categorization, he writes on the projected pages of accounting problems as he teaches. “So the drill exercises are a quick nail down of the concepts that the students need to know early on. And then, they’re not fumbling with it later, and I try to use keywords to trigger their learning …,” he says.

Dr. Schneider said he aims to serve as a “source and fountain of encouragement,” while making it clear to students that they need to do the necessary work. His organizational methods pay off when students grow more confident in their abilities. They realize that they can solve accounting problems, and for graduate students that may lead to the conviction that they possess the knowledge to pass the CPA exam. Goals for acquiring accounting skills, including those required for the CPA exam, are among the objectives listed on the syllabi for different courses.

In Dr. Dunn’s courses, she uses methods from a different arsenal of effective teaching strategies. Her goal is to make her expectations of students clear so that they understand what she expects from them and what they need to do to meet the course’s competencies. These competencies are learning goals similar to objectives, which she provides to students on the course’s syllabus.

The assignments follow an organized process. She provides the initial grounding that students need to be successful by providing examples with the assignments. After the deadline for assignment submissions, Dr. Dunn provides an example of a correct assignment to reinforce student learning.

Student Feedback

The following excerpts of students’ comments on the organizational techniques practiced by Drs. Schneider and Dunn illustrate how helpful these techniques are for students.

Student Comments

“Whenever I do not understand a specific topic, I just turn to that section in the packet, and the way that it is explained is so simple. There are many charts with arrows that show how each item is interconnected.” (Accounting student in a course taught by Dr. Schneider.)

“She gives appropriate assessments and feedback. She sets (a) clear goal and (an) intellectual challenge. … Her PowerPoints are well-organized.” (Technical Writing student in a course taught by Dr. Dunn.)

Advantages of Organized Courses for Faculty and Students

Faculty and students may find that an organized approach provides a smoother classroom or distance learning experience.

Faculty Benefits

- Provides structure for faculty

- Improves performance in the classroom

- Encourages engagement in the classroom

Student Benefits

- Provides structure for students

- Clarified class content for students

- Engages students

Summary

At ECU, Drs. Dunn and Schneider teach different subjects but both rely upon course organization to streamline the learning process for their students. They aim to provide course content that is clear and consistent, and presented in a well-organized manner. In Dr. Schneider’s accounting classes, he relies on material he created to meet the course objectives. He projects the exercises onto a screen in class so that students can see the steps he takes to solve the problems. In Dr. Dunn’s Technical Writing courses, she includes examples with the assignments to spur students on to understanding. She also provides weekly PowerPoints and each distance learning class receives online videotaped lectures via Tegrity in their weekly folders.

The building blocks of organization for Dr. Schneider are the textbooks he writes which he calls lecture packets. All of the material is coordinated to work together and works in conjunction with the coursework he posts to Blackboard.

Dr. Dunn uses online folders as the building blocks of organization. Weekly folders are posted for face-to-face and distance learning courses, containing PowerPoint slides, an assignment, along with an example of that assignment.

Drs. Dunn and Schneider’s attention to organization is considered by students to be a contributor to their success in these courses. Such student comments buttress the literature that shows that highly organized courses support student learning.

Learn More

Literature Base

Editor’s Note: The Literature Base section of each College STAR module provides a brief summary of support for the instructional practice highlighted within the module. This is not an exhaustive literature review. It is designed to give the viewer an introduction to the literature about the module’s instructional practice. Please consider using the Learn More section of the module to supplement the information you obtain through this Literature Base summary.

One way college faculty can improve learning in the classroom is by designing courses so that content and delivery are clearly arranged—a research-proven approach that heightens student understanding. Teachers who were prepared and organized contributed to student achievement (Feldman, 1989).

Organization of a course was rated as the highest ranking attribute of students “grading” the performance of economics faculty in course evaluations (Boex, 2000). In that analysis, students indicated that “organization and clarity” were the most important qualities faculty could possess. Their importance intensified for more advanced students. “The impact increased at more advanced levels of study: organization and clarity was more important for graduate students than for undergraduates and more important in the noncore courses than in core courses” (p. 220). Carroll and O’Donnell (2010)also found that providing an organized course is one of the ways that faculty can promote a supportive learning atmosphere, according to their study of students’ perceptions of learning.

Another study based on teaching videos indicated that a well-organized lecture course led to higher gains in student achievement, especially among those students unfamiliar with the subject, such as students enrolled in introductory classes (Schonwetter et al., 2002). Course organization included faculty’s explanation of the course and the stressing of important points. Other admirable organizational traits identified in the study included faculty possessing a thorough knowledge of the material and the ability to make prudent use of class time.

Lumpkin and Multon (2013) turned the tables on the typical research formula, instead identifying the qualities possessed by highly regarded faculty from their perspective, not from students’ impressions. Time management of the classroom, and the course’s organization and structure, were tops among the traits that faculty associated with effective teaching. These traits were considered key to helping students learn.

A well-organized course may smooth the way for faculty, but it’s geared more towards helping students succeed. One way to assist students in managing their study time is to include grading policies, allowing them to structure their efforts accordingly. (See the corresponding module, titled “Using Syllabi to Organize Courses,” to learn more providing grading criteria and using syllabi as part of an overall organizational plan.) A course that includes well-chosen assignments that reinforce concepts also helps students learn (Carroll & O’Donnell, 2010). One way to engage students is to explain the purpose or real-world applicability of assignments (Hockensmith, 1988; Slattery & Carlson, 2005). Another way to help students is to consider their different learning styles. Assignments, projects, and exams that make room for submissions that use various formats allow students to use the learning style they prefer (Dunn et al., 2009). A learner-centered instructor offers students options for completing their work (Blumberg & Weimer, 2009).

The overall organization of the course can take different forms. It could be organized “logically,” according to a theme or according to the “big picture,” or it could follow a “natural chronological order” (Hockensmith, 1988, p. 346). An organized class requires planning and a commitment by faculty (Brophy, 2010). Sufficient planning allows the class to operate more smoothly with students staying occupied, with less transition time between class activities.

Adept management helps students regulate their own learning, particularly under the tenets of social constructivist pedagogy, where students learn through active processes overseen by the instructor (Brophy, 2010). “[Class management research] findings converge on the conclusion that teachers who approach management as a process of establishing and maintaining effective learning environments tend to be more successful than teachers who emphasize their roles as authority figures or disciplinarians (p. 41).” Organization encompasses the way the course is structured and the clarity of lectures and presentations. Providing an organized course helps faculty create a “supportive and encouraging learning environment” (Carroll & O’Donnell, 2010, p. 65).

References & Resources

Blumberg, P., & Weimer, M. (2009). Developing learner-centered teaching: A practical guide for faculty. San Francisco, Calif.: Jossey-Bass, A Wiley Imprint.

Boex, L. F. (2000). Attributes of effective economics instructors: An analysis of student evaluations. The Journal of Economic Education, 31(3), 211-227. doi:10.1080/00220480009596780

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00220480009596780

Brophy, J. (2010). Classroom management as socializing students into clearly articulated roles. Journal of Classroom Interaction, 45(1), 41-45.

Retrieved from EBSCO

Carroll, N., & O’Donnell, M. (2010). Some critical factors in student learning. International Journal of Education Research, 5(1), 59-69.

Retrieved from EBSCO

CAST (n.d.) About CAST: What is Universal Design for Learning. Retrieved from http://cast.org

CAST (2009). CAST UDL online modules. Retrieved from http://cast.org

Dunn, R., Honigsfeld, A., Doolan, L. S., Bostrom, L., Russo, K., Schiering, M. S., . . . Tenedero, H. (2009). Impact of learning-style instructional strategies on students’ achievement and attitudes: Perceptions of educators in diverse institutions. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 82(3), 135-140. doi:10.3200/TCHS.82.3.135-140

http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/TCHS.82.3.135-140

EnACT. (n.d.) 14 common elements of UDL in the college classroom.

Evans, C., Williams, J. B., King, L., & Metcalf, D. (2010). Modeling, guided instruction, and application of UDL in a rural special education teacher preparation program. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 29(4), 41-48.

Retrieved from Education Research Complete

Feldman, K. A. (1989). The association between student ratings of specific instructional dimensions and student achievement: Refining and extending the synthesis of data from multisection validity studies. Research in Higher Education, 30(6), 583-645.

Feldman, K. A. (1989). The association between student ratings of specific instructional dimensions and student achievement: Refining and extending the synthesis of data from multisection validity studies. Research in Higher Education, 30(6), 583-645. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40195923

Hockensmith, S. F. (1988). The syllabus as teaching tool. The Educational Forum, 52(4), 339-351.

Immordino-Yang, M., & Damasio, A. (2007). We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education, Mind, Brain & Education, 1(1), 3-10. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-228X.2007.00004.x http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-228X.2007.00004.x

Lumpkin, A., & Multon, K. D. (2013). Perceptions of teaching effectiveness. The Educational Forum, 77(3), 288-299. doi:10.1080/00131725.2013.792907

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2013.792907

Retrieved from Taylor & Francis Online

Murray, H. (1991). Effective Teaching Behaviors in the College Classroom. In. J. Smart (Ed.) Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research (Vol. VII), (PP. 135-172). Bronx, N.Y.: Agathon Press.

National Center on Universal Design for Learning. (2011). About UDL. Retrieved from http://www.udlcenter.org/aboutudl

Rose, D., & Dalton, B. (2009). Learning to read in the digital age. Mind, Brain & Education, 3(2), 74-83. doi:10.1111/j.1751-228X.2009.01057.x

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-228X.2009.01057.x

Rose, D. H., Harbour, W. S., Johnston, C. S., Daley, S. G., & Abarbanell, L. (2006). Universal design for learning in postsecondary education: Reflections on principles and their application. Journal of Postsecondary Education & Disability, 19(2), 135-151.

Retrieved from Education Research Complete.

Rose, D. H. & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching every student in the digital age: Universal design for learning. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum.

Retrieved from http://www.cast.org

Ruohoniemi, M., & Lindblom‐Ylänne, S. (2009). Students’ experiences concerning course workload and factors enhancing and impeding their learning – a useful resource for quality enhancement in teaching and curriculum planning. International Journal for Academic Development, 14(1), 69-81. doi:10.1080/13601440802659494

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13601440802659494

Schonwetter, D. J., Clifton, R. A., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Content familiarity: Differential impact of effective teaching on student achievement outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 43(6), 625-655.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40197278

Slattery, J.M., & Carlson, J. F. (2005). Preparing an effective syllabus: Current best practices. College Teaching, 53(4), 159-164. doi: 10.3200/CTCH.53.4.159-164

http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/CTCH.53.4.159-164

UDLCAST. (2011, October 7). Introduction to UDL [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MbGkL06EU90&feature=relmfu

Additional Resources

APA Style: A DOI primer. (2009). Retrieved from http://blog.apastyle.org/apastyle/2009/09/a-doi-primer.html

CAST: Center for Applied Special Technology. (1999-2013). Retrieved from http://www.cast.org

CrossRef. (2013). DOI Resolver. Retrieved from http://crossref.org

International DOI Foundation. (2012). Resolve a doi number. Retrieved from http://www.doi.org

Lenz, B. K., Schumaker, J.B., Deshler, D.D., Bulgren, J.A. (1998). The Course Organizer Routine. Lawrence, KS: Edge Enterprises.

Goldstein, G. S., & Benassi, V. A. (2006). Students’ and instructors’ beliefs about excellent lecturers and discussion leaders. Research in Higher Education, 47(6), 685-707. doi:10.1007/s11162-006-9011-x

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11162-006-9011-x

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11162-006-9011-x/fulltext.html

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40197572

Retrieved from JSTOR

About the Author

Dr. Carolyn Dunn

Technology Systems

East Carolina University

Dr. Douglas Schneider

Department of Accounting

East Carolina University